“The fires are longer and hotter,” says Ryan Moreside, a crew leader for BC Wildfire Service. “And they’re burning all through the day and night.” Moreside is among the 1,880 firefighters and firefighting support workers who are part of the BC General Employees’ Union (BCGEU).

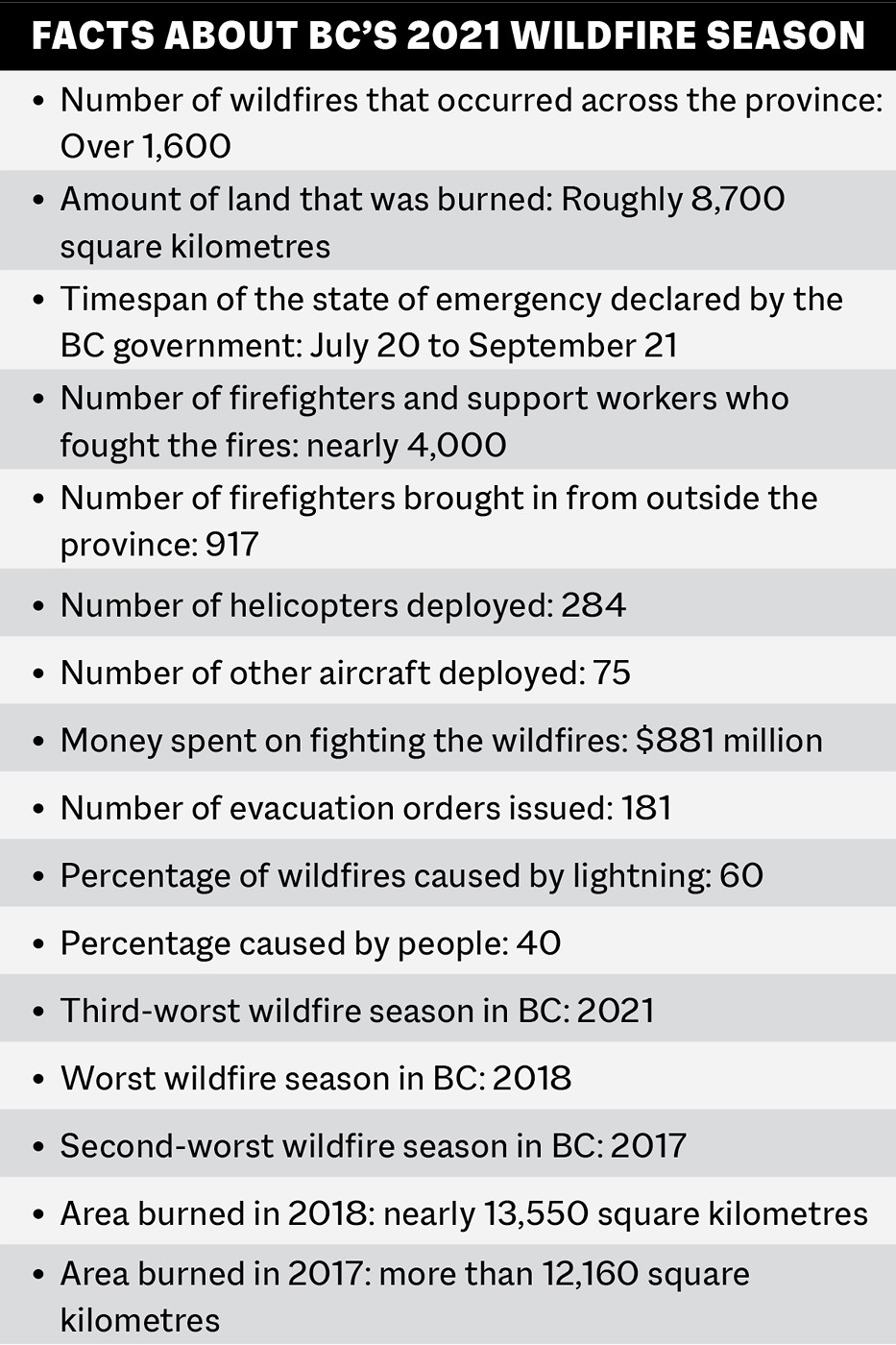

A six-year veteran of the service, Moreside fought three major wildfires near his Penticton home in the Okanagan Valley in the summer of 2021. It was the third-worst fire season in BC history. Along with enduring extreme temperatures, he and his crew were forced to cope with the added challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It started out as tiny smoke over a reserve,” Moreside says about a fire that began at Inkaneep Creek, near the town of Osoyoos, on July 19. “Two houses were in the direct path of the fire. Our crew evacuated the homes and released the livestock.”

Ryan Moreside is a crew leader for BC Wildfire Service. He fought three major wildfires near his Penticton home in the Okanagan Valley in the summer of 2021. PHOTOGRAPH: Courtesy BCGEU

As the fire spread across the Osoyoos Indian Band reserve, the crew was able to save the two houses. Eventually more help arrived, including workers with helicopters and bulldozers. “It became a blur as it got dark at 10 o’clock,” Moreside remembers. “We were going to be there for the next 15 hours, steering the fire away from buildings and letting it burn up into the fields. The fire was so big we couldn’t extinguish it.”

Soon after his team evacuated more residents living up the road from the creek, an official evacuation order was given, impacting residents of 200 properties on the reserve.

Over the next three night shifts, Moreside fought the fire. “It’s easier to work at night,” he says. “There’s less wind, and the temperature is down, but we are still chasing the fire.”

When there are so many fires around the province, he says resources get tied up. It takes a few days to set up the crew; meanwhile, the fire keeps spreading. “There’s 100-foot flames,” Moreside says.

Osoyoos band members worked with the wildfire service, telling firefighters about cultural sites to be aware of. “They know the land better than us,” he says. “They informed us where they don’t want the fire to go and where it can go.”

Over the course of the summer, Moreside worked five-day shifts with a crew of 21 people, racking up 50 days on the fire line.

The Nk’Mip Creek wildfire, as it was later renamed, was finally contained by September 2, after burning an estimated 19,335 hectares.

As for future preparations, he says prescribed burns in the fall and spring are helpful, removing biomass fuels like deadwood and thinning the forest. His crew has done this work with six young members of the Lower Similkameen Indian Band over the past four years, benefiting the habitat and providing fire protection.

Meanwhile, the BCGEU is preparing contract negotiations for 2022, and Moreside, who has auxiliary employee status with recently accrued benefits, says improving the retention rate of firefighters is important. He notes that many co-workers use their job as a stepping stone to employment at municipal fire halls, where the work continues all year long and the pay is much better.

“We need a professional core,” Moreside says. “We need core people with knowledge who work year-round.

“I love this job. I receive great support from my supervisors,” he also says. Still Moreside believes the issue needs attention and so does the chronic fatigue that often comes with it. “I felt it this summer, and I’m sure my co-workers did too. The harder the summer, the sweeter the off-season.”

“The service is treated as seasonal, and there are a number of bad effects because of that,” says BCGEU treasurer Paul Finch. “They have been incredibly burned out by this onerous season. They need appropriate wages across the sector that address the retention issue, and more even schedules.”

Finch says the membership ranges from auxiliaries, many of them university students, hired to fight fires for a few seasons, to long-term employees who have been on the job for more than 20 years. Firefighters shouldn’t have to work past age 55, asserts Finch, but frontline workers in the BC Wildfire Service are not yet recognized as firefighters under the Canadian Income Tax Act. If they were, as public safety professionals they would be allowed to take early retirement. “Our firefighters can’t retire early at age 50 and can’t accrue pensionable service. Much of their work is overtime and not properly compensated. This means there’s a high turnover, and this significantly diminishes our services.”

The union has started meeting with the government on issues of concern, Finch says, and is gathering feedback from the rank and file for upcoming contract negotiations.

Among the key issues is the government’s practice of bringing in additional firefighters, support workers and equipment on a contract basis instead of investing more funds in the BC Wildfire Service itself. “We should be a standalone, independent service with year-round employees, and we should be hiring on a seasonal basis,” Finch says. “But that’s not happening now. If the government invests in training, recruiting and retention, we’ll have better outcomes.”

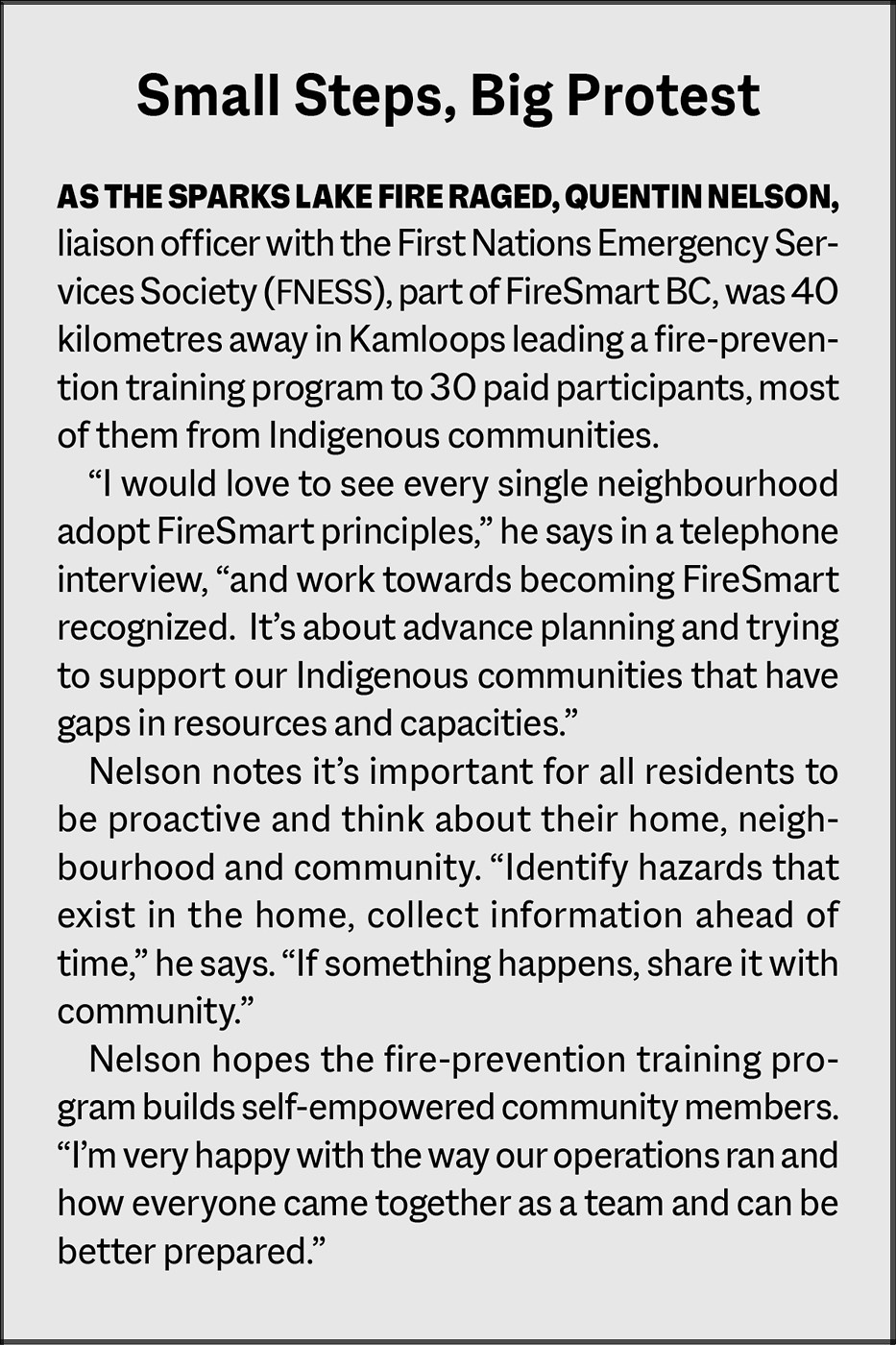

The Sparks Lake wildfire, the largest of the summer wildfires, raged for two months within a massive dry belt in south central BC. Residents in the area had already coped with the Elephant Hill wildfire in 2017 and, in its aftermath, undertook massive tree planting along with improving their preparations for future fires. BC government initiatives with First Nations included the purchase of fire-suppression equipment and the upgrading of fire guards — dirt roads strategically cleared of trees and other vegetation, to serve as barriers. Ranchers, loggers and other residents in rural communities were braced for fire season too.

Those preparations helped when the Sparks Lake fire ignited on June 28, 2021, says Joanne Hammond, director of archaeology, heritage and environment at Skeetchestn Natural Resources Corporation, a company owned by the Skeetchestn Indian Band. Four days after flames spread across the valley above the reserve, an evacuation order was given to 350 Skeetchestn band members. Though not a band member, Hammond stayed behind along with 75 others, taking on the role as second in command at the incident communication centre.

Joanne Hammond is director of archaeology, heritage and environment at Skeetchestn Natural Resources Corporation, a company owned by the Skeetchestn Indian Band. PHOTOGRAPH: Matt Meuse

“After seven weeks, the fire was a serious threat to the reserve,” she says. “There were about five Skeetchestn Firewatchers with experience. They had a sense of the wind and weather. They worked shifts around the clock. It was hard to see it from a helicopter, with all the smoke. On the ground, Firekeepers were able to share their services and knowledge with the BC Wildfire Service firefighters.”

Support came from other provinces — and countries — as fires spread around the province. While outside help was appreciated, Hammond says some of the firefighters could be problematic.

“They have the mindset that the terrain is the same everywhere, which it isn’t. Local Indigenous people have learned about the land from their parents and grandparents. They have a really unique understanding of fires and are able to share this with BC Wildfire.”

Unit firefighter crews of 20 people move around the province, working two weeks on, with three days off. “Rotating firefighters in and out was problematic too,” Hammond says. “It made for tricky relations [with local residents] and there were chronic complaints about this.”

A Skeetchestn support team attended to the gardens and pets left behind on the reserve. “This was so people had a home to come back to. For six weeks there was no real daylight. It was yellow all day, and hot. It was difficult for workers to keep up. It was exhausting.”

Fortunately, the reserve was never in the direct line of the flames, which spread above and across from the valley. By September 5, the Sparks Lake fire was under control, but 60 per cent of Skeetchestn Territorial Land had been destroyed. “We kept the fire from the community,” Hammond says, “but there is a massive loss of natural resources and terrain used for hunting and fishing and gathering.

“There is the risk of washouts and landslides,” she also says. “The fires were on steep terrain. The one road to the reserve is still closed.” Hammond is concerned about visitors going into the bush. “They should not be entering burned zones.”

Fires and flooding have been happening more frequently, Hammond points out. The effects of climate change are keenly felt here. And, Hammond continues, bound up with climate change is increased industrial interference, the disappearance of plants and animals, and invasive species coming into the habitats. She believes the shift in landscape means BC needs more Firewatchers, firefighters and support personnel.

Darrel Peters, a Firekeeper and territorial patrol leader with the Skeetchestn Indian Band, played a key role in fighting the Sparks Lake fire.

“This land is our dinner plate, where the medicine is,” Peters says. “I spent two months away from my other work to fight the fire. I’m playing catch-up now on my other jobs.”

Peters and the on-reserve crews had experience fighting the Elephant Hill fire in 2017. “I’m in control here,” he says, “but off reserve, I’m not.”

His approach is different from the wildfire service crews who come in. “I fight directly. They fight indirectly. I make my plan, where I want people situated, making sure no one gets hurt. I use radio communication before I start and make sure my bases are covered.”

Peters usually works alone, driving around and then getting out of his vehicle to have a look at where the fire is moving. “I have a cellphone and an SOS signal as well. It’s safety first. I read the fire, where it goes, how much it takes up. I find a high point [on the land], a bird’s-eye view. I’m a key person and can go anywhere.”

Working on the Sparks Lake fire, he partnered with Skeetchestn band member Samantha Draney, a Firewatcher handling the maps and GPS work. “The two of us collect information,” he says. “We work with the government crews.”

Darrel Peters, a Firekeeper and territorial patrol leader with the Skeetchestn Indian Band, spent two months away from his other work to fight the Sparks Lake fire. PHOTOGRAPH: Matt Meuse

Peters was in a helicopter a few times but is not convinced modern tools, including digital maps, provide the best way to fight fires. “You don’t see what’s on the ground,” he says.

The wildfire service chain of command is too slow making decisions, he adds. “It takes one hour to talk to the boss, then the next man spends an hour talking to his boss. Three days have passed by the time decisions are made.” This was especially true, says Peters, when the Sparks Lake fire started. “If there had been a quicker response, we’d have the fire dealt with quicker.”

The “upper table” is the source of the problem, Peters believes, not the firefighters on the ground. “They have a meeting. I need to be part of it.” His message to the decision-makers: “Work with me.”

Peters’ ability to read fires comes from doing prescribed burns in the spring and fall. His great grandmother, grandmother and mother were Firekeepers, and their knowledge was passed on to him. “It’s a gift,” he says.

Side hill burns have been traditionally ignited and controlled with heat that is light or moderate, he explains. “Some plants need it, some don’t.” Besides encouraging growth of edible plants, prescribed burns also yield forests that are easier to navigate.

“Some people think they can do it, but it takes skill. You can lose control. You need to know where the fire is going, how far it’s going, the wind, time of day, type of fuel. You need to read the fire.

“Prescribed burns were outlawed back in the day, but it’s my right and my tradition. I was raised on this as a kid and will pass it on to my son and daughter.”

When a crisis like the Sparks Lake fire happens, Peters says having relationships with people across their Territorial Land is important. He makes a point of knowing everyone. “The old-timers, the children and their children’s children,” he says. “I keep things open because I could be knocking on their door. I could need a hand.” He wants them to know they are well looked after too. “We are one big family.

“I’m one of the lower workers, but when the fire comes, I step up to the top and everyone listens, including the Chief of the [Skeetchestn] Council. I have the education about the land and when push comes to shove, I have the knowledge. When I make a decision, I look at the pros and cons. I watch and learn and look at all the little things. I set the bar high and put out 110 per cent, and that’s what comes back.”

Skeetchestn community members are back home now, dealing with the aftermath of the fire. Since the heavy rains started, Peters says, there’s been charcoal-coloured water in the creek, raising concerns about the fish that will be spawning and the coho salmon coming up in the main creek. Because of the conditions, those fish could contract gill disease, he says.

“This impacts on everything. There’s the timber, mule deer and birds.” He, like Joanne Hammond, worries about the effect human beings are having on the land and its capacity to recover. “People from outside the area are coming in now, and they shouldn’t be. The government needs to step up and close some areas so things can rejuvenate.”

When the Sparks Lake fire broke out, Samantha Draney set aside her work as cultural heritage lead with the Skeetchestn Natural Resources Corporation to work as a Firewatcher alongside Darrel Peters and other Skeetchestn members.

Firewatcher Samantha Draney set aside her work as cultural heritage lead with the Skeetchestn Natural Resources Corporation to work alongside Darrel Peters and other Skeetchestn members when the Sparks Lake fire began. PHOTOGRAPH: Samantha Draney

“I came in on the second day, working 12 hours some days and four hours on other days,” Draney says.

She was taught the traditional ways by her grandmother and her older cousins and has taken courses at college and with BC Wildfire Services. “The ideal way to fight wildfires is using Indigenous practices braided with western knowledge,” Draney says. Her other skill is a knowledge of the land. “Darrel is a hunter and knows the land that way,” she says. “I’m a land user, gathering plants.”

At age 30, Draney has already had experience as a Firewatcher. “In 2017, we created maps and safety plans after the Elephant Hill fire,” she says. This summer she did similar work, driving around, then hiking up to a vantage point to study the fire and relay information back to Peters. “I use a cellphone and iPad and collect data in real time as the fire changes. The wildfire service shared data with us on a daily basis.

“The BC Wildfire Service fights from the back,” Draney observes. “They are more worried about settlements as assets than the land. First Nations people see the land as an asset. The water, plants, animals. The open land. When the BC Wildfire Service back burned the land [a strategy to fight the fire], they were not recognizing this. The back burns get away on them, unless they are planned with a Knowledge Keeper.”

She says a Knowledge Keeper does not always have to be Indigenous. “That person could be an 80-year-old rancher who knows the land, the wind and the weather,” though, she cautions, “the rancher might not take in First Nations’ view of land as an asset.”

Draney says the 2017 Elephant Hill fire was the start of relationship building with wildfire service firefighters, but more needs to be done. “You might not see the firefighter again,” she says about their rotating shift work, “and the next one may not be as good. The higher-ups in the wildfire service are part of the old-guy group. They don’t see our values as equal. The younger ones are more willing to work with us.”

Darrel Peters at the Sparks Lake fire. When a crisis like the Sparks Lake fire happens, Peters says having relationships with people across their Territorial Land is important. PHOTOGRAPH: SAMANTHA DRANEY

Draney points out her cousins and other Indigenous people are hired seasonally by BC Wildfire Service but are assigned outside their Territory, as was the case during the Elephant Hill fire. “They need to fight fires where they live,” Draney says. “Their knowledge isn’t used. They’ve hunted this land. They know the waters, and they will bring a passion to the job.”

When the Tremont Creek wildfire ignited on July 12 and spread to Skeetchestn Territory, Draney says relations with the firefighters became “unhealthy.” Their attitude was “‘what are you doing here?” and “you’re in the way,” she says.

The firefighters’ decision to do a back burning left her and other Skeetchestn members angry and in tears. “This does hurt us. I went with my grandmother to harvest medicinal plants in the Tremont Lake area. Now this land is gone.” She told the firefighters, “You’ll leave us sick, spiritually, physically, emotionally.”

Paul Finch says the BCGEU recognizes the “new normal” when it comes to wildfire season, and the need to implement Indigenous-led fire management practices. The union is committed to improving relations with community members impacted by the fire, he says. “The BCGEU wants to establish protocols to ensure Indigenous governance is respected on their Territories, and wants to see proper recruitment and retention inside the crews as well as alongside them.”

Meanwhile there will be tree planting, improved preparations and an effort to build stronger relations between government and community members. “We have to be ready for the next time,” says Hammond.

Janet Nicol is a Vancouver freelance writer and frequent Our Times contributor. Read her accompanying interview with Ingrid Pond, a smokejumper with the BC Wildfire Service. Nicol's previous article, "COVID Chronicles: A Working People's Living History," featured the BC Labour Heritage Centre’s project to collect stories of frontline workers impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.