“My boss knew that I was gay . . . But also at the same time, she would pull me aside and say things like, ‘well, I support you. I don’t know if other parents in the community would. You might want to keep it under wraps.’” — from “Work Inclusion and 2SLGBTQ+ People in Windsor and Sudbury”

In the past four decades, Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and/or queer people (2SLGBTQ+) have won great advances in legal rights and social equality in Canada. Same-gender couples in Canada can now legally marry, human rights legislation in most jurisdictions explicitly prohibits discrimination on the grounds of gender expression and identity, and same-sex partners are eligible for the same employment benefits as heterosexual couples. Increasingly, 2SLGBTQ+ people are taking up space in public conversations and in media. Given all of this, some feel that trans and queer people have achieved equality in society and at work.

2SLGBTQ+ activists, scholars and allies, however, have often suggested that the experiences of different members under this umbrella vary considerably. In the media and elsewhere, we often don’t hear from, or about, working-class 2SLGBTQ+ people or those living in smaller cities, particularly cities with industrial legacies.

A research partnership between McMaster University, the University of Windsor, Unifor, the United Steelworkers (USW), the Sudbury Workers Education and Advocacy Centre and the Windsor Workers Education Centre aimed to address this gap by documenting the experiences of these workers, while asking this question: what role can unions play in creating safe and supportive workplaces and enhancing life for 2SLGBTQ+ workers?

The multi-year study focused on the Ontario cities of Windsor and Sudbury. It took a community-engaged, mixed-methods approach, starting with an online survey followed by semi-structured interviews. The survey and the interviews were broad and exploratory, asking participants about their work, health, and community experiences. Six hundred and seventy-three people filled out the survey, and from there we did 50 interviews — about 25 in each city. Community members and union partners in both Windsor and Sudbury provided input on the study’s design, helped to spread the word and, when the time came, to communicate the results. Those results, touched on here, are also available at length in the project’s report, “Work Inclusion and 2SLGBTQ+ People in Windsor and Sudbury.”

Seeking Safety at Work

Data from the surveys and interviews painted a detailed picture of participants’ work lives. Overall, many of them did not feel comfortable in their workplaces. Just over half of respondents said they concealed their identity from either supervisors or co-workers, or during teamwork or work events. Racialized respondents were even more likely to hide their sexuality or gender identity than those who were white. Many participants also spoke of feeling uneasy at work.

When asked if he felt comfortable at his construction job, one gay man (participants’ names have been withheld to protect their privacy) from Sudbury said, “Um, most of the time I do. There’s definitely times where I feel uncomfortable just because it’s . . . I just don’t feel comfortable dealing with racists and bigoted ideas and people . . . my sexual orientation doesn’t come into contact with my job at all, but that’s mostly just my choice of whether or not to come out at different times.”

He went on to say, “Like, in the past I might have come out in earlier jobs, but I don’t think I’d come out during [my construction job]. That’s just kind of insane.”

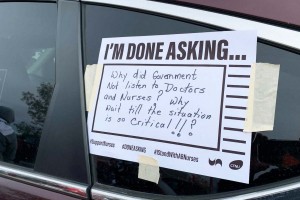

Sudbury Pride Parade, July 20, 2019. PHOTOGRAPH: SUZANNE MILLS

When it came to being out at work, a sense of comfort and safety depended on which industry people worked in. Almost two-thirds of respondents who worked in mining or manufacturing said they hid their gender identity and sexual orientation from everyone at work.

2SLGBTQ+ workers, the study also shows, choose to avoid certain lines of work — even though the pay, benefits and job security may be excellent — because they perceive or experience some workplaces as being much riskier than others.

One transgender man who had a trade certification but was working in a call centre listed those jobs he would avoid applying for until he could pass as a man: “Anything pretty much in the industrial field, so anything when it comes to like mining, industrial shops, factories, things of that nature,” he said. “Definitely until I get top surgery is when I’m hoping to finally feel like I would be okay to apply and work in one of those fields, but right now that’s definitely a mental barrier I have.”

Include 2SLGBTQ+ workers

Currently, the Employment Equity Act requires employers of federally regulated industries to report on the hiring and retention of four groups: women, Indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities. Because 2SLGBTQ+ workers actively avoid certain sectors and workplaces, it is especially timely and all the more relevant that the federal government is currently involved in consultations to update and expand that legislation.

Employers could soon be required to make their workplaces safer and more welcoming to members of the community. But much needs to change — accurate reporting about hiring and retention of trans and queer workers will be a challenge when so many are still feeling unsafe and experiencing discrimination at work. They may well feel the only real option is to remain silent about their gender identity or sexuality. As well, any reporting done in unsafe work environments could also increase the level of danger that 2SLGBTQ+ people experience.

Many workers in the sample reported that discrimination based on sexual orientation and/or gender identity prevented them from advancing in their current job, with racialized workers three times more likely than white workers to encounter this.

Subtle and overt discrimination

Respondents also reported experiencing subtle and overt discrimination from co-workers, supervisors and customers that negatively affected their feelings about their job. Over 60 per cent of respondents shared that they had experienced homophobia or transphobia from co-workers or customers at some point in their work life. While the most common experiences of discrimination were subtle forms of exclusion — such as avoidance or eye-rolling — verbal harassment and bullying were also prevalent in the sample.

“I always feel like I have to hide or choose what I’m going to show to people,” said one bisexual woman from Windsor. “There’s this one guy working there and he liked me and I was his friend . . . and then he found out that I preferred women and he flipped.” She went on to describe how he harassed her. “He started like calling me all sorts of names and like telling everybody that I’m a this and a that and every time I saw him, he would crack nasty jokes, so that was not fun.”

While overt discrimination — such as verbal harassment, sexual harassment and physical assault — was found across the total sample, racialized workers experienced it at much higher rates. Nearly a quarter of Black LGBTQ+ workers reported experiencing physical violence from co-workers, violence based on their sexual orientation or gender identity — six times higher than the rates reported by white respondents.

The Importance of Feeling Connected

Approximately three per cent of Indigenous respondents reported experiencing physical violence from co-workers. Though Indigenous respondents often reported more positive experiences and less discrimination than racialized and white participants, this finding must be qualified. Taken alone, the statistics hide the experiences of racism and legacies of colonialism Indigenous workers spoke about often in their interviews.

What a number of Indigenous participants mentioned was the importance of feeling connected to Indigenous and Two-Spirit communities within the 2SLGBTQ+ community. One Indigenous woman, who initially felt that she didn’t fit within Sudbury’s 2SLGBTQ+ community, described how she actively went about building strong connections: “So, as a queer person, in the beginning, I never really felt a part of the queer community because it was very limited to mostly gay and lesbian people, but now, over time, I’ve developed a queer community for myself. Also, as an Indigenous person there’s a lot of good community things happening and places to go to like get better acquainted with my Indigenous heritage and learn more and participate in activities.”

The Power to Make Things Better

A large proportion of the people who took part in the study also reported living with anxiety and depression arising from stigma, harassment and isolation. Workplaces had the power to make these problems worse, or better. Nearly three-quarters of survey respondents had experienced a mental health issue related to their work over the past year, with the most common types of work-related mental health issues being anxiety, depression and panic attacks.

“You know, some I guess is just the general stress of being a trans woman in a male-dominated workforce, I guess just as a general weighing on you,” said one transgender woman who worked in an unsupportive workplace. “Just, you know what it’s like, you know, any weight you carry for a long time.”

Supportive workplaces and unionized workplaces, on the other hand, had the power to mitigate mental health issues. These workplaces were linked to good mental health, whereas poor mental health was strongly correlated with precarious and non-unionized work.

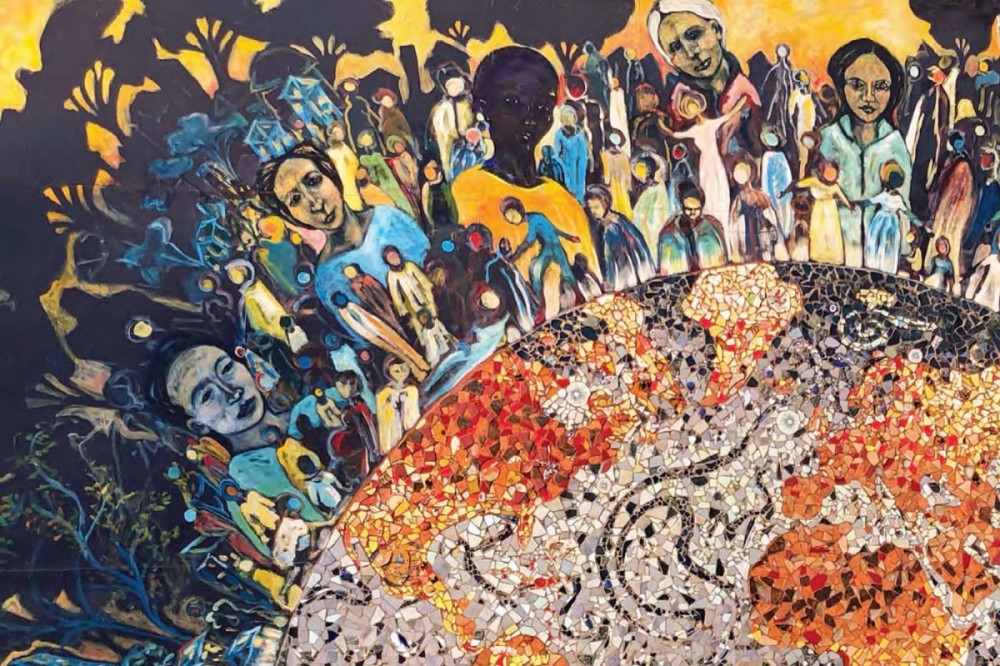

Artist Sarah King-Gold created this mural on Elgin Street in Sudbury, with the help of two high school students, Rita Luopa and Amber Hanna. PHOTOGRAPH OF MURAL DETAIL: SUZANNE MILLS

Given the study’s focus on Windsor and Sudbury — two small cities with strong industrial histories — it came as no surprise that the distinct industrial and cultural makeup of each region factored into the study’s results. Like many cities in Canada, Windsor and Sudbury have changed dramatically over the past 30 years. Automotive manufacturing in Windsor and mining in Sudbury are still important, but not as prominent as they once were. More people now work in the service sector than in either of these industries. But what we saw from our study participants — who were more likely to work in service jobs — was that the industrial culture of these cities still exists.

The Struggle to Find Decent Work

The perception of Windsor and Sudbury as regions with deeply engrained blue-collar cultures led participants in the study to hide their identities, affected which jobs they applied for, and related to their experiences of discrimination. For some, ‘good’ blue-collar jobs can feel unsafe, making it difficult to find decent work.

“It is a struggle, I mean finding gainful employment,” said one gay man in Windsor. “I’ve been fortunate enough to work in a lot of atmospheres that have been very accepting, but with the hyper-masculine environments, it means a lot of hostility for many non-traditionally-masculine men to be working in these spaces . . . So it can be very difficult to navigate moving up through work spaces in the city for sure.”

Another participant — in this case a bisexual woman from Windsor — explained how she had to narrow her job search: “I knew that any place I worked had to be a safe space, so that became very important. So yeah, I tended to look at non-profits, very social justice-y things, anything that pretty much looked like it was not a guarantee but a pretty safe bet.”

Despite these experiences of feeling unsafe in industrial work environments, 2SLGBTQ+ workers’ experiences in the service sector demonstrated how safety at work was related to more than just job culture. It also depended upon job quality and the nature of these workers’ interactions with the public.

Good Jobs Mean Better Mental Health

In the survey, half of service workers reported experiencing discrimination from customers. Transgender respondents and racialized respondents reported discrimination from customers at even higher rates. These workers were also the least likely to be unionized or feel protected by their union, and the most likely to report experiencing mental health issues related to work.

“I’ve actually had a customer who told management that she would never be back unless I was fired, because I stood firm whenever she would call me ‘she,’” said one transgender man from Sudbury. “I’m like, ‘he.’”

While participants from blue-collar workplaces were more likely to experience discrimination from co-workers, it became apparent that service-sector workers were more likely to experience discrimination from customers.

Interestingly, those working in blue-collar jobs reported better mental health than people in more precarious jobs, including those in the service sector. This speaks to the fact that having a ‘good job’ that is unionized, has health benefits, and offers predictable full-time work is important for one’s mental health, even if people are facing discrimination.

2SLGBTQ+ people, particularly those without post-secondary education, might be missing out on some of these ‘good jobs,’ and are instead trapped in precarious, unstable and low-paid work environments that they perceive to be more accepting. With that said, there were unaccepting work cultures across all industries, and people in our study often moved from job to job until they found a more welcoming work culture — or they stayed in the closet at work.

Sudbury Pride, 2019 (left to right): Scott Florence, Shandel Valiquette, Roxanne Savoie, Mélodie Bérubé, Benjamin Owens. Scott, Shandel and Mélodie work at the Sudbury Workers Education and Advocacy Centre (SWEAC). PHOTOGRAPH: SUZANNE MILLS

“This project’s results are a rich source of ideas and guidance for all unions,” says Adriane Paavo, USW’s representative on the project steering committee and national head of education and equality for the Steelworkers. “To build on what our union is already doing, we’re asking 2SLGBTQ+ Steelworkers to review and reflect on the findings, then say how our work should expand in light of them.”

For workers who are unionized, unions have extensive programs that focus on member education and on human rights, as well as mechanisms to raise complaints. Indeed, almost 60 per cent of unionized participants said their unions protected them from discrimination based on sexual orientation and/or gender identity, and another 30 per cent said their unions somewhat protected them.

These experiences of supportive unions, though, were not universal: transgender workers and racialized workers were much less likely to feel like their union has their back. “[My union local] does nothing, nothing,” asserted one non-binary worker from Windsor. “[It] doesn’t even put like a flyer up or any kind of anything . . . not even like for Pride . . . it’s like it doesn’t exist. Yeah, they are pretty weak like that, weak in their support and mindset.”

Unions Can Do Better

“This study revealed heartbreaking stories of workers who were not provided a safe work environment, and either avoided completely or had to leave a good union job,” says Sarah McCue, Unifor LGBTQ liaison and a national representative with the union. “And in reply, respondents asked for the simplest solutions, for their unions to put up a Pride flag and provide some education to their harassers.”

McCue goes on to say, “I think we can do better than that, by raising the bar in collective agreements, demanding fairness from employers and providing services to members, and many already are. Unifor mandates human rights education for all elected union executives, and provides a growing list of activist trainings for queer and trans members, specifically.”

But, she stresses, “These services — the protection of a collective agreement, and enhanced benefits — are only available to workers who join a union, so any strategy to target discrimination at work needs to be delivered with a union card.”

Protected and Connected

Some unionized participants, though, discussed feeling disconnected from their unions. This, in turn, prevented them from getting involved or accessing supports. When asked whether she would feel comfortable going to the union for help, a lesbian woman from Windsor responded, “I can’t say that it would be the first thing that would come to my mind as somewhere to go.” She felt that “It’s a bit of an elusive thing that exists that I know that I’m a part of . . . that I’m not involved in.”

Unionized study participants who did feel protected and connected to their unions shared a range of practices their unions had adopted to make their workplaces feel more supportive and inclusive. These included their union taking a strong stance on harassment, creating 2SLGBTQ+ caucuses and committees, and promoting 2SLGBTQ+-specific education and training.

“Our union is very on top of, like, peer-on-peer harassment,” one gay man from Windsor explained. “Again, I wasn’t part of the union before, so I was really, really surprised coming into [work] and they come and check up on you every shift, so they’ll ask you if anything is wrong, and I’ve never had that before, right?”

Others talked about how their union had 2SLGBTQ+-specific groups that provided a forum for community-building and amplified the voices of 2SLGBTQ+ members. One lesbian woman explained that the 2SLGBTQ+ committee in her union advocated for the use of inclusive language in collective agreements, promoting union-wide change.

Inclusive Collective Agreement Language

“The [union], I think, are doing a phenomenal job,” she said. “You know, it’s inclusive language and little box stuff, spearheading, you know, let’s get some language in agreements for transitioning and all of the stuff . . . that’s where the LGBTQ advisory community comes in.”

Finally, some participants also described how their union — and even some employers — provided anti-oppression education that touched on 2SLGBTQ+ inclusion. These training sessions showed the union’s commitment to 2SLGBTQ+ members and fostered positive relationships between workers.

In the words of one transgender woman who took part in one of these training sessions, “it was the most wonderful experience, and I just couldn’t get enough of [the training] after that, so I took more courses.”

Windsor Pride Parade, 2018: PHOTOGRAPH ADRIAN GUTA

“Union education programs are powerful tools,” USW’s Paavo agrees. “2SLGBTQ+ members see themselves reflected in course content and see their unions take their lives and concerns seriously. And other members get these messages, too.

“Unions have also worked hard to weave gender equality and anti-racism through all the education we do, to add to how we think about the roles of stewards, OHS [occupational health-and-safety] reps, and local union officers, and we need to do the same with justice based on sexuality and gender identity.”

But Paavo is wary of seeing education as the only tool, when unions prioritize collective bargaining and political action and when changes in union structure and staff or activist roles — like the role of trans liaison officer — can be key ways to give voice and space.

“At the end of the day, union life is lived out in the locals and on the shop floor,” she asserts. “And that’s where the workers who took the survey experienced the bad and the good of work. So how do we apply the research findings to the lives of local unions? That’s what I’m most excited to discuss with the reference group of 2SLGBTQ+ Steelworkers.”

When asked what unions could do more of, participants said they wanted their unions to more actively support 2SLGBTQ+ workers, both symbolically and with concrete measures. Being outspoken allies to the 2SLGBTQ+ community is an important place to start. In the words of one transgender woman from Sudbury: “Silence is often taken as being against, so by not actually being verbally supportive of that, it is a missed opportunity.”

After completing an MA in Labour Studies at McMaster University, where he studied experiences of customer violence among 2SLGBTQ+ service-sector workers, Benjamin Owens worked as a research coordinator for the 2SLGBTQ+ inclusion project at McMaster University and at Covenant House Toronto. His current work focuses on 2SLGBTQ+ workplace inclusion and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people experiencing homelessness.

Special thanks to Adriane Paavo, Sarah McCue and Suzanne Mills for their assistance with this article.

The contributors would like to thank Mélodie Bérubé, Adrian Guta, Randy Jackson, Nathaniel Lewis, and Natalie Oswin for their contributions to the larger Work and Inclusion project from which this article is derived. John Antoniw, Lee Czechowski, Angela Di Nello, Laurel O’Gorman, Leah McGrath Reynolds, and Kai Squires provided research assistance. Community members Bobby Jay Aubin, Derrick Carl Biso, Dani Bobb, Vincent Bolt, Lynne Descary, Debra Dumouchelle, Dana Dunphy, Mel Jobin, and Paul Pasanen contributed to the design of interview questions and participant recruitment. The Sudbury Workers Education and Advocacy Centre, Unifor, and the United Steelworkers provided indispensable in-kind support of space and staff time to help with the project.

Some interview responses have been edited for length. Visit the project's website and read the full report here.