Many of us in the BC labour movement are familiar with the story of Albert "Ginger" Goodwin. The abridged version is this: a coal miner and pacifist originally from Treeton, England who worked in the Cumberland mines on Vancouver Island, Goodwin became a labour organizer, fighting for workers' safety. In 1918, he was shot and killed by a special constable in the woods near Cumberland, and every year, the town honours his memory during its Miners' Memorial Weekend. People gather for a graveside vigil, placing flowers on Ginger Goodwin's grave and on the graves of all fallen miners buried there.

AN OLD STORY AND A NEW STRUGGLE

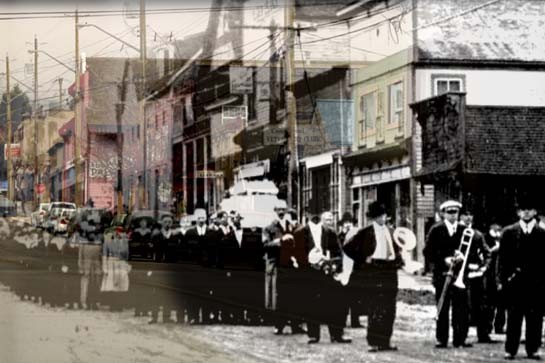

In Neil Vokey's feature-length film, Goodwin's Way, we learn there is some intrigue to the story. We see the story of Goodwin through a blending of vintage photos with present-day images of Cumberland, where much of the old architecture is still intact. We hear local residents tell what they know about the shooting of Ginger Goodwin.

However, the film is more than a simple re-telling of Goodwin's story. Vokey has woven together the story of Goodwin, the history of Cumberland as a community reliant on resource extraction, and the present-day struggle by some residents to protect their community from a proposed new coal mine.

Vokey first attempted to capture the story of Ginger Goodwin in a 12-minute short film, made while he was a student at the Capilano University Film Centre. He entered the film in the 2011 Canadian Labour International Film Festival and it was screened across Canada. (Disclaimer: I am on CLiFF's board of directors, and I was so impressed with his 2011 student film that last year, when Vokey started a crowd funder to produce his feature-length film, I contributed to it.) While the BC labour movement may know Goodwin's story, it was long past due that the story be made into a film.

FOLLOWING WORK IN THE COAL MINES

Cumberland is in the north part of Vancouver Island. In the 1800s, a rich deposit of coal was discovered, and so started the development that would bring workers like Goodwin to the mines. Goodwin was working in Nova Scotia at the time, but had to leave when he was added to a list of undesirables for his involvement in strike action. Workers also came from other countries, such as China and Japan. Indeed, my mother's side of the family emigrated from Japan in the 1800s to work in the coal mines. Mining was tough, brutal work, and the conditions in the Cumberland mines made it even more deadly.

In the film, Susan Mayse, author of the book Ginger: The Life and Death of Albert Goodwin, says "Cumberland mines were still using what they called 'tea kettles.' They were tiny little oil lamps that were clipped to the front of a soft cap, not even a hard hat." Mayse explains that the mines on Vancouver Island were known to have so much methane gas in them, one spark from a lamp could set off an explosion.

One striking set of archival images highlights the aftermath of an explosion, with sound effects, and then leads into a camera shot that pans over the Cumberland cemetery. Superimposed is the startling statistic that, of the 1,000 deaths in mining accidents on Vancouver Island, 295 happened in Cumberland.

We learn that Goodwin was a persuasive speaker who practised by talking to tree stumps in the woods. Under the mentorship of Joe Naylor, local president of the United Mine Workers of America, he became involved in the 1912-14 strike, which started when a union-appointed gas inspector was fired for reporting unsafe levels of gas in a mine. Goodwin was added to a list of undesirables again, and the film tracks his story as he made his way to Trail, BC, where he organized smelter workers. Goodwin rose quickly through the labour ranks, becoming president of the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers, District 6; president of the Trail Trades and Labour Council; and a vice-president of the BC Federation of Labour.

GOODWIN TARGETED

The First World War had started and men were being conscripted. Although Goodwin was against a war that used working men to kill working men, he did sign up. By all accounts Goodwin was known to be in poor health, plagued by dental issues and stomach problems. He also suffered from what was known as "miner's TB," caused by years of exposure to coal dust. He received a medical exemption, but, two weeks later, after he organized a strike of 1,500 smelter workers, he was declared fit for duty. Many locals feel he was directly targeted for conscription because of his union work.

Goodwin returned to Cumberland, and, along with other draft evaders, lived in the woods. Supporters provided food and supplies so he could remain hidden from the police. The Dominion Police hired trackers and special constables to assist them in the search. Dan Campbell, who was skilled in shooting and tracking, was hired as a special constable. He was a former BC Provincial Police officer who had been kicked off the force for extorting a bribe.

Campbell killed Ginger Goodwin on July 27, 1918. On that point, everyone agrees.

Director Vokey arranges a sequence of clips of Cumberland citizens sharing their version of stories heard and passed down. Locals like Gordon Carter (who sings a great song during the end credits) and Frank Carter share the story told to them by their father. Their father's friend, Jimmy Randall, was with Goodwin that day. After shooting Goodwin, Campbell told Randall, "Bugger off or you're next." "What my dad said is that 'Jimmy Randall never ever told a lie in his life,'" says Gordon Carter. "Whatever he told my dad I've always thought would have to be the truth." It's compelling to watch as these locals share their pieces of the story.

Campbell claimed self-defence and was initially charged with manslaughter but, in the end, the case did not go to higher court. Campbell was a free man.

Neil Vokey’s film blends old history with new struggles. PHOTOGRAPH:GOODWIN’S FUNERAL IMAGE COURTESY OF THE CUMBERLAND MUSEUM AND ARCHIVES [C110-001]

TAKING TO THE STREETS

The camera pans across an archival shot of a massive funeral procession stretched along the main street of Cumberland. In a voice-over, local historian Ruth Masters says that during the many years she has lived in the town, "I've never seen a funeral parade that looked anything like that. Ever." Most of the workers believed Goodwin had been murdered, and his death set off a one-day general strike in Vancouver, the first of its kind in Canada.

The film also includes a quick montage showing pivotal events in Cumberland's history, such as the closure of its last mine. Especially striking are class photos taken in 1941 and 1942, juxtaposed to show the sudden disappearance of Japanese Canadian children from classrooms. Gone because, after the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbour, 22,000 Japanese Canadians on the West Coast, including my family, were forcibly removed from their homes and businesses and unjustly incarcerated in internment camps. I appreciate that this event was included.

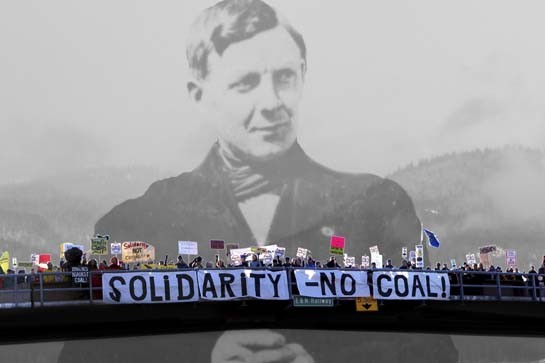

Cover image of the film Goodwin’s Way PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY NEIL VOKEY

In the film, these past events are interspersed with the present day — some current residents and First Nations are shown taking action against a proposed coal mine in the area. The community's history is tied to coal mining but, as Cumberland mayor Leslie Baird says, the town is still dealing with slag heaps and contamination from old mines, so its residents are struggling with the new proposal.

Neil Vokey's interest in the story of Ginger Goodwin was sparked when he became curious about the removal of highway signage with the words "Ginger Goodwin Way" on it. The signs had been installed by the BC NDP in 1996 and were promptly taken down by the BC Liberals when they came to power in 2001 — a lesson in how history can be hidden unless we fight to keep our stories known, and celebrated.

Vokey's film reveals the enduring legacy of a man who has been dead for nearly 100 years, and perhaps also the reason a government would fear a sign that could inspire people to rebel — in Ginger Goodwin's way.

Goodwin's Way was produced in association with the Capilano University Bosa Centre for Film and Animation, and the Lefthand Media Co-op. It was directed and produced by Neil Vokey in 2016 (Washboard Films).

Lorene Oikawa speaks and writes on a range of topics including women in leadership, human rights, social media, and labour history. She is the president of the Greater Vancouver Japanese Canadian Citizens' Association (GVJCCA) and a director on the boards of the Canadian Labour International Film Festival (CLiFF) and West Coast Environmental Law.

The founder of the Asian Canadian Labour Alliance in BC, Oikawa served three terms (2005-2014) as an executive vice-president for the BC Government and Service Employees' Union (BCGEU) and was the first Asian Canadian at the executive level.

Today, she works for the Province of BC in the Ministry of Social Development and Social Innovation.