The U.S. presidential election is fast approaching. In this special series, six writers focus on workers, deindustrialization, and the rise of right-wing populism in the United States, England, France, Italy and Germany.

_______________________

The United States goes to the polls in November to choose its next president after four turbulent, chaotic and deeply troubling years under Donald Trump. Until the pandemic struck with deadly force, most commentators believed that it was still his election to lose. Trump’s complete failure to manage the public health crisis has changed the political dynamic, but he could still win. What accounts for his continued popularity?

Ever since Trump’s election in 2016, a debate has raged over the underlying reasons for his victory. Many believe that racism, and racism alone, accounts for it. The New York Times even called on its middle-class readership to “leave behind” the “Left Behind Theory” — which is predicated on the idea that voters geographically and economically left behind delivered the victory. According to this logic, racism, not class betrayal, explains the rise of Trump.

Class analysis and race analysis are becoming ever-more polarized. Sociologist Satnam Virdee, among others, has encouraged us to challenge this deepening polarization and instead recognize the relationship between capitalism, class struggles, and racial inequality. The working class is often coded as white in the media, when in fact it is multi-racial, not just in the U.S. and Canada, but in Europe too.

In 2016, the Democrats lost the electoral college when the “Blue Wall” states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin and Iowa fell to Trump. All five states had voted for Barack Obama twice. That they are all in the U.S. Rust Belt strongly suggests that class played a part. County-level voting data largely confirm this assumption. The Democrats dropped 20 per cent in many deindustrialized areas. One study found that union households in Ohio that voted for Obama by a margin of 23 per cent in 2012 voted for Trump by 9 per cent in 2016. These working-class swing voters are not easily dismissed as racists — though they are overwhelmingly white, and that matters.

Trump gained 335,000 voters across these five states from households earning less than $50,000 per year, but Hillary Clinton lost 1.17 million of these voters. Many working-class voters of all racial backgrounds stayed home.

All of this suggests that the party of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal has a growing class problem on its hands.

A sense of rage and betrayal runs deep in working-class communities. I have interviewed hundreds of displaced workers over the years and that much is clear.

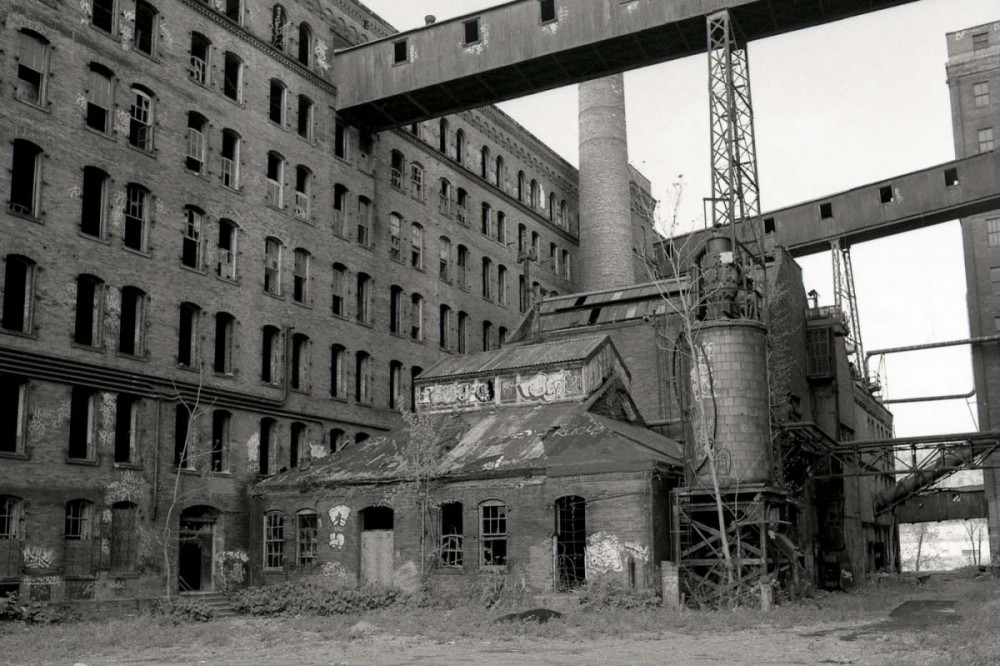

McLouth Steel, near Detroit, Michigan, was one of the many steel mills that closed across the U.S. Rust Belt. PHOTOGRAPH: DAVID W. LEWIS

The populist revolt has been a long time in the making. Jimmy Carter fought inflation instead of unemployment in the 1970s and Barack Obama bailed out the bankers instead of homeowners in 2008. Democrats have championed the very trade agreements that have levelled industrial America. Eight million manufacturing jobs were lost between 1979 and 2010. Most recently, Bill Clinton gave us the North American Free Trade Agreement.

It is therefore telling that Trump, not Hillary Clinton, pounded away at the injustice of these trade agreements and the loss of manufacturing jobs to low-wage areas in other countries. And, it is sadly ironic that it was Trump who insisted on renegotiating NAFTA in order to better protect U.S. workers. It was great political theatre and might yet help deliver him another victory.

The deindustrialization of the United States, and Canada, has been a disaster for working people. Yet some middle-class people who see themselves as progressive have welcomed these sweeping changes. These were dehumanizing and polluting industries, often male-dominated, and very much bound up with empire. Any one of these concerns can politically re-contextualize an industrial closure into a public good, especially when one is socially distant from those most directly affected.

However, there is something more going on. When anthropologist Kathryn Marie Dudley interviewed teachers in deindustrializing Kenosha, Wisconsin, they told her that maybe now their working-class students would take their education seriously. As Dudley notes in her book The End of the Line: Lost Jobs, New Lives in Postindustrial America, factory closures served as a “status-degradation ritual — a cultural recognition that blue-collar laborers are of a lower social status than they have been pretending to be.”

For some university-educated people, blue-collar workers had simply not earned their middle-class wages or lifestyle. Upward social mobility for many working people was collectively bargained rather than individually achieved. There is little room for solidarity among those who actually believe that we live in a meritocracy.

In a meritocracy, those at the bottom deserve to be there.

Now more than ever, we need to break with the false dichotomy of race versus class if we are to offer a credible alternative to right-wing populism. More neoliberal centrism will simply push more of us into the waiting arms of right-wing populists.

________________________

This series is sponsored by Concordia University’s “Deindustrialization & the Politics of Our Times” research project, funded by Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Steven High is a professor of history at Concordia University's Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling (COHDS). He is leading a seven-year transnational research project on the politics of deindustrialization.