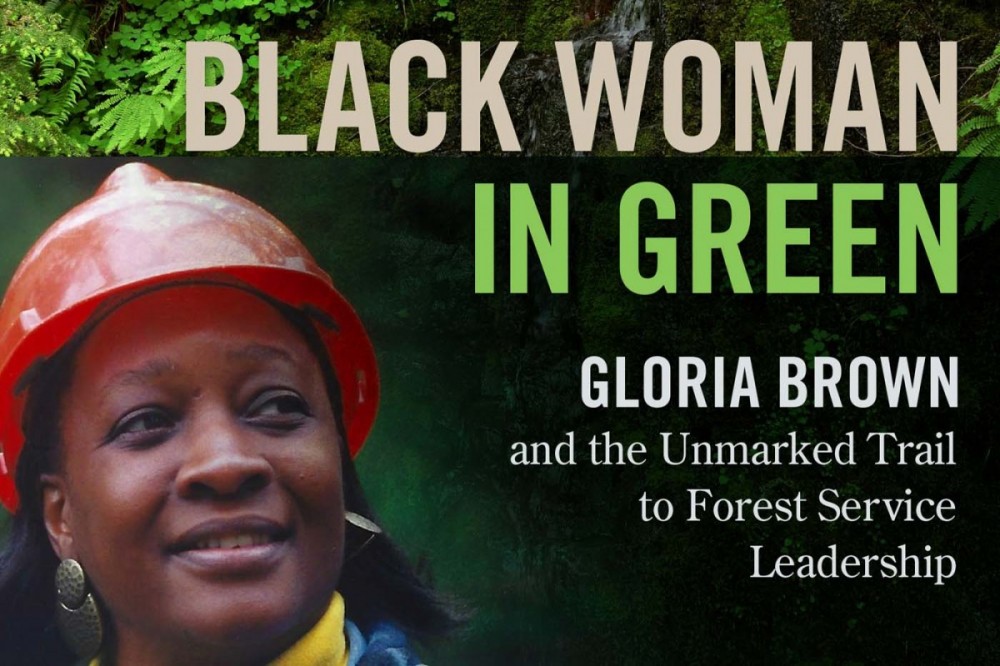

BLACK WOMAN IN GREEN: Gloria Brown and the Unmarked Trail to Forest Service Leadership

By Gloria D. Brown and Donna L. Sinclair

Oregon State University Press (2020)

$19.95, 190 pages

ISBN: 978-87071-001-8

“Nobody looks like us — two Black women — in the classic adventure stories,” asserts Jacqueline Scott, a Ph.D student at the University of Toronto, who publishes a blog called Black Outdoors. “Instead the tales are filled with white men and women on grand tours of the wilderness. They did these because they were fun, a challenge, or a quest to walk in the footsteps of bygone explorers.... We are tired of being the only Black faces in what seem to be coded as white spaces.”

Scott shared her reflections in “Black Canada Hike: Claiming our Outdoor Space,” a December 2019 essay that she penned for the CBC Sports website. In the absorbing piece, she discussed her plans to begin, this year, a transcontinental journey with a Black woman friend. The coronavirus has likely compelled the duo to delay the adventure that would have taken them from British Columbia to the Maritimes.

The Lack of Racial Diversity

Like others who’ve lamented the lack of racial diversity in North American parks, campgrounds, and conservation areas, Scott can rejoice in the release of Black Woman in Green. The riveting memoir (written with historian Donna Sinclair) chronicles the life of Gloria Brown, the first woman of African descent to attain the rank of supervisor in the United States Forest Service.

A former clerical worker for the agency headquartered in Washington, DC, Brown’s world was shattered when, in 1981, her husband died after an impaired driver barrelled into their car. “The doctor took my hand and led me to the room where Willie James was lying, broken glass still on his face,” writes Brown, who sustained minor injuries in the collision. “I tried to clean it off.” She continues: “I was thirty years old and suddenly a widow with three children. Now what do I do? Where do I go? How do I go on? Why go on?”

At the time of the accident, Brown had been enrolled in evening journalism classes at a local university. Her husband’s tragic death strengthened her resolve to build a better future for her family. “That’s when I began to see the Forest Service as my salvation,” she writes. “I had planned to become a television reporter. . . . Now I could not afford to start at the bottom of print or a live medium. . . . I decided to figure out how to get from A to B to C in an organization that had been predominately white and male for three-quarters of a century.”

A Shimmering Green Landscape

To that end, Brown completed her journalism degree. At work, she identified mentors who could help her negotiate the Forest Service hierarchy. Driven to succeed, she was soon promoted to Information Specialist — a position for which she took her first-ever plane flight, to attend a meeting in Oregon. In moving passages, she recounts her introduction to the shimmering green landscape that she embraced as the “hue of deliverance” for her family.

“When I saw the massive trees, bigger than any living thing I had seen in my life. . . I felt that I was in a cathedral,” Brown writes. “I had sent out pamphlets about forest ecology but had never seen old growth. For me, visiting the forest was like going into a darkroom and having the light come on slowly to reveal a new world.”

Inspired by her trip to Oregon, Brown later secured a Forest Service public affairs job in Montana. Her training included a mule ride into the state’s backcountry.

Blatant Racism and Sexism

“I found myself surrounded by people who had worked half their lives in the woods, who shared stories about hunting and fishing,” Brown writes, noting the distinctive dark-green “pickle-suit” uniform of Forest Service employees. “For the first time, I had to buy a pair of steel-toed boots designed for working in the woods. I even learned how to build a fire line by digging the real thing!”

On the down-side, Brown was also subject to blatant racism and sexism in Montana. While she ignored comments from Forest Service colleagues who bemoaned the presence of women and minorities in “their world,” she took quick action when her daughter was labelled a “troublemaker” and blamed for a brawl at her school. “My children learned that racism was always lying just beneath the surface, ready to explode unexpectedly,” she declares.

Upset by the racial climate in Montana, Brown returned to Oregon where she joined the management team of the Willamette National Forest — home to wildlife species such as the northern spotted owl, sockeye salmon, elk, and black bear. There, she found herself embroiled in heated 1990s-era debates among loggers, environmentalists, and politicians about forestry conservation. Despite challenges to her leadership, she pressed on: “Adversity can strengthen you if you persevere, and I knew I would,” she writes. “I had ambitions.”

By the late 1990s, the author had overseen the regeneration of the Mount St. Helens volcano site, discovered romance with a Portland bookshop owner, advanced her education in forestry, and celebrated the personal and professional success of her children. Emblematic of the authenticity that Brown brings to the narrative, she writes, “Despite this good news. . . . I still felt like a widow who never had enough. I could never forget how hard life had been after my husband died.”

A Ground-Breaking Career

Brown’s candour about the challenges she faced (i.e., a white male colleague who “joked” about shooting her for “target practice”), heightens the impact of her landmark ascent, in 1999, as supervisor of Oregon’s sprawling Siuslaw National Forest — the first Black woman to hold the position. She’d later also head the Los Padres National Forest in California where her duties included wildfire management.

About her ground-breaking career, Brown offers insights that echo Jacqueline Scott’s observations about “minorities” in the outdoors: “Fewer people of color work in the Forest Service today than did in the 1990s. . . . Increasing and maintaining diversity. . . takes real commitment by leaders. . . . My actions and decisions left our public ecosystems in better shape than I found them. This makes me proud.”

The author of Alice Walker: A Life, Evelyn C. White is a Halifax-based journalist.

If you like what you're reading and want to subscribe, please go here. Thank you!