The story of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada — now over a year in its writing — has also inevitably become a story about work. Overnight, “essential” entered day-to-day vocabulary to describe those workers whose in-person jobs our society couldn’t function without. Many workers temporarily enjoyed fanfare and public appreciation. Others even briefly received hazard pay.

But for many workers, their material conditions have not improved in proportion to their essential status. Rather, the long-lasting problems typical of the retail sector — low pay, unfairness, inadequate health and safety, and unsupportive management — have only become more intense. And as with most workplaces, the pandemic has made those problems unignorable.

But retail workers are pushing back and organizing their workplaces, led by the women and People of Colour who have long been overrepresented in the industry. A growing wave of union drives across Canada in stores of all kinds — including cannabis dispensaries, coffee shops and bookstores — is creating alternatives to the status quo. In fact, Canadian economist Jim Stanford recently noted in the Toronto Star that participation in unions hasn’t been this high in over 15 years. The trend is thanks in no small part to retail activism.

Coast to coast, these workers share not only a common hunger for change, but are actively charting a new course in a sector known for instability and insecurity. If the story of the pandemic is one of work, then organizers have proven it’s also one of fightback.

Organizing Bookstores

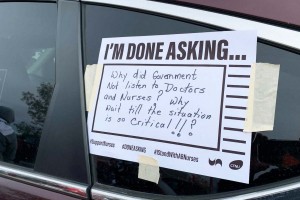

When the first lockdown was announced, in March 2020, retail workers at Indigo Books and Music were faced with looming uncertainty and confusion. The mega-bookstore chain, the biggest of its kind in Canada, had furloughed roughly 5,200 employees nationwide at the beginning of the pandemic and left the remaining workers to grapple with unclear management policies.

In multiple stores across the country, Indigo’s retail workers were frustrated with corporate leadership and store management’s indifference towards shop-level employees. At the Indigo in Mississauga, Ontario’s Square One mall, retail employees were fighting against the mismanagement of their pandemic-related compensation, the absence of paid sick days and emergency leaves, and the lack of transparency regarding workers’ safety.

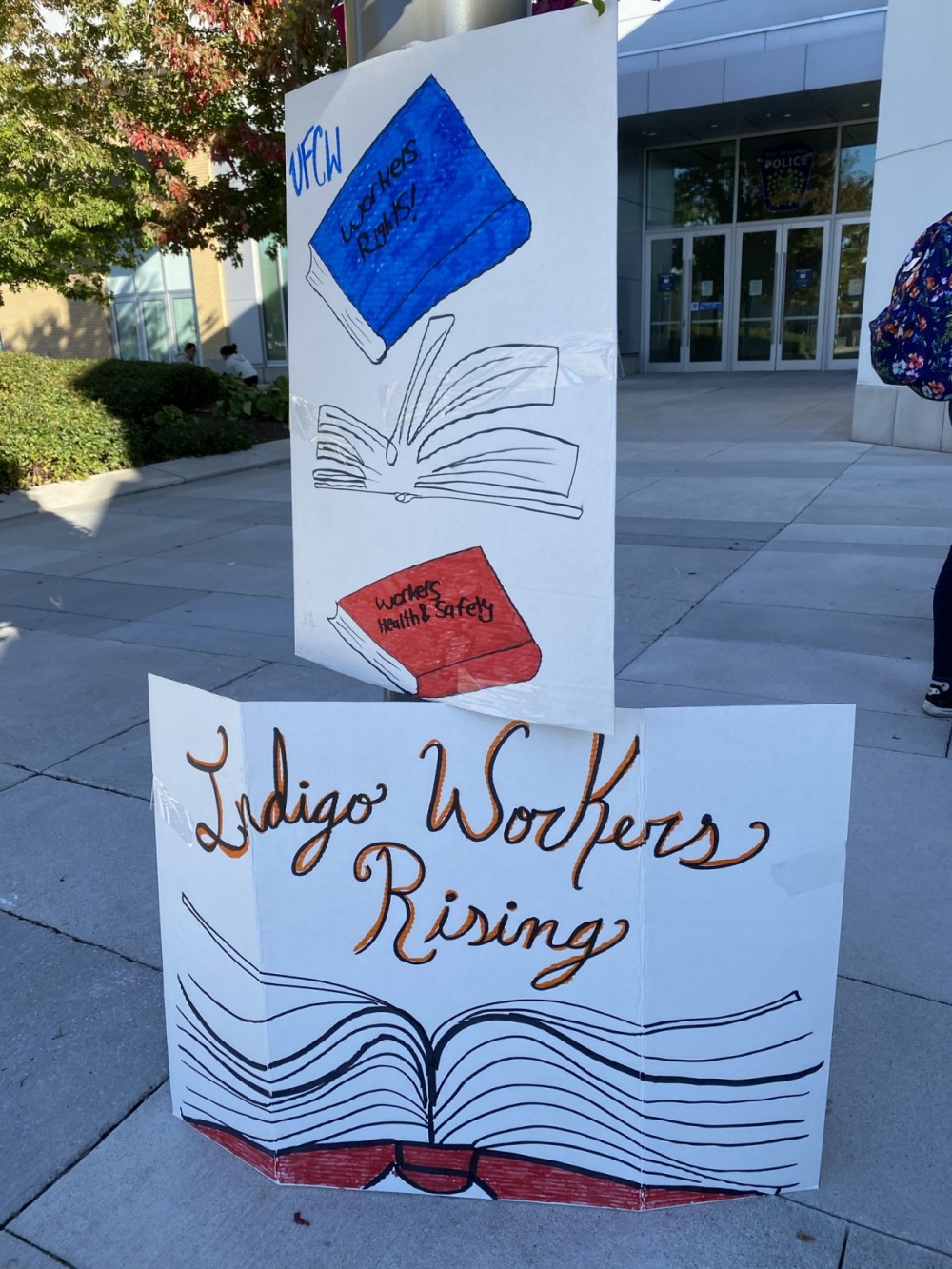

The workers launched a campaign to unionize and won the vote in October 2020, joining UFCW Canada Local 1006A (United Food and Commercial Workers). Within a few months of unionization, the multi-million-dollar bookstore chain met most of the demands of Square One’s retail workers and introduced additional company-wide policies that would create a more equitable workplace.

“As soon as our store voted to unionize, we all got a 10 per cent raise all of a sudden and 10 hours of extra sick leave,” shares Jennifer, one of the retail employees who led the unionization effort at Indigo Square One. Indigo has also introduced a benefits program for all employees, regardless of years of service or type of employment contract, and the company’s corporate leadership is increasing its efforts to engage with retail workers.

While the workplace changes that have come on the heels of the successful union drive are welcome, Jennifer is still wary of management. “I’m also thinking, like, are you doing this as a way to discourage other stores who are thinking about unionizing?” she says, noting that Indigo has been circulating memos to store managers that outline strategies to identify unionizing efforts.

Following the success of the Square One union drive, discussions about workplace organizing began at other Indigo stores, and more of them voted to unionize — the store in Woodbridge, Ontario; Chapters Pinetree Village, in Coquitlam, British Columbia; and Indigo Place Montréal Trust in Quebec. Workers noted that the simultaneous campaigns in Quebec, British Columbia and Ontario benefited from the wealth of educational material and strategic learning produced by Square One’s campaign.

Alex, who works at Indigo Place Montréal Trust, was involved with the campaign that led to the store becoming the first and only Indigo outlet to unionize in Quebec. “The pandemic was one of the main factors related to my decision to unionize,” states Alex. The workers there voted to join the Canadian Office and Professional Employees Union (COPE). “I was further galvanized through my months-long furlough, with managers telling me half-truths about people being called back to work and the number of labour hours available.”

Unionizing for Equity

The domino effect of Indigo stores unionizing across the country solidified a harsh truth about the company that workers have known for years: that the bookstore does not care about its retail employees, despite the essential nature of their work. This was especially concerning for marginalized and racialized workers, who make up a good majority of Indigo’s retail workforce.

Jennifer, at the Square One store, claims that she “only ever witnessed white men and women get tapped for management roles.” The case seems to be the same at the Place Montréal Trust store, where mostly white employees get recognized for promotions.

“I think Indigo tries very hard to cultivate an anti-racist image but ultimately it operates within a capitalist culture which disadvantages workers and People of Colour as an ideological axiom,” says Alex.

At the height of the Black Lives Matter movement in the summer of 2020, Indigo CEO and founder Heather Reisman sent an internal note acknowledging that the organization needed to better address systemic racism. In the months following, the company’s social media brimmed with publicity focused on anti-racism. By October, around the same time as the Square One store’s unionization victory, the bookstore pledged to represent more Black authors on its roster.

The surface-level attempts to address racism, however, felt hollow in light of the company’s treatment of its largely racialized retail employees. “That’s the myth of the corporate social-responsibility model that Indigo adopts — no matter how much they try to magnify Black or Indigenous authors when it’s politically expedient, or how good they make themselves look through philanthropy, they still turn around and pay us peanuts,” Alex says.

“If you care about my Black life and you say that you’re doing anti-oppression work through your business model, part of that should be wanting to preserve my Black life by making sure that when I’m in your store, I am protected,” expresses Jennifer. “[You should be making sure] that I’m being paid fairly and equitably and that I deserve access to proper health care.”

A growing wave of union drives across Canada in stores of all kinds — including cannabis dispensaries, coffee shops and bookstores — is creating alternatives to the status quo.

The unionization campaigns in both Square One and Place Montréal Trust were led by workers who identify as Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC). According to Alex, “the decision to unionize represented a rejection of the terms of recognition as Indigo’s managerial culture set them.

“I think there’s also something to be said about being a workforce made up of primarily Anglophones in Quebec,” he continues. “As an additional layer, I think Anglophones who are visible minorities find themselves shut out of the broader cultural and political dynamics of the province, which leads to many simply checking out. I think a union allows us to claw back some economic power in a province whose institutions largely do not want to represent us.”

For BIPOC workers at Indigo, unionizing was a way to build their own democratized institution that recognized the true value of their labour — and bargained for its fair price.

Cannabis Dispensary Drives

Deemed an essential service by the federal government, cannabis dispensaries quickly became retail battlegrounds for labour organizing. Both a multi-billion-dollar industry and an emerging one — rife with inexperienced management and gaps in employment standards — the cannabis space has proven fertile ground for activists.

Tanya, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, is a dispensary worker who was involved in organizing Tokyo Smoke in Stoney Creek — a community in Hamilton, Ontario. She’s also active with the cross-workplace movement United Weed Workers (UWW), a volunteer-based grassroots organization founded in Hamilton, Ontario, that works in solidarity with cannabis workers everywhere.

Tanya describes the challenging, precarious conditions in which many cannabis workers operate, conditions that existed even before the present health crisis. She notes that “the transition from the legacy market to the legal market” has been rocky. Swaths of stores in the cannabis space lack basic health-and-safety standards, she says, including things as simple as fire codes or security protocols — the latter being a growing need given recent upticks in dispensary robberies. Perhaps it’s a hangover from the “cowboy cannabis days” that these gaps exist, Tanya says, but “there’s no reason why” they should be acceptable.

“People [who run cannabis companies] just aren’t paying attention to these things,” she says. “[But] the Employment Standards Act exists for a reason. It’s not as if they don’t have the information.” She argues that workers have been made into “guinea pigs,” and that they “have to be the responsible ones that say ‘no, this isn’t right.’

“It also goes to show that people still don’t take labour rights seriously,” she continues. “And they think that because our generation of young people are less educated about their rights at work, they can take advantage of that to save a buck.”

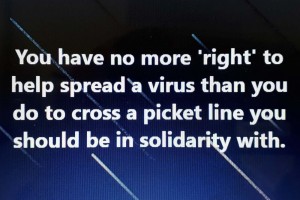

During the pandemic, access to PPE and other on-site safety tools quickly became an issue. Tanya explains, for example, that workers struggled to obtain plexiglass barriers and have often been expected to serve unmasked customers picking up orders curbside — among various other contraventions of standards.

The Campaign is Born

The Stoney Creek store’s union drive materialized against this backdrop. Feeling unsupported by management who failed to resolve their complaints, Tokyo Smoke workers mounted a campaign to take things into their own hands. The main drivers, in Tanya’s eyes, were “a lack of health and safety, and unfairness at work.” Initiated by her co-workers, the campaign took off, and Tanya soon found herself in a leadership position, particularly when it came to educating her co-workers.

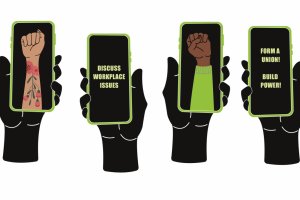

In fact, Tanya believes education played a decisive role. “We were armed with information,” she says, which “made us stronger when our voices were united.” After explaining to her co-workers that a fightback was completely possible and legal, “people weren’t afraid,” she says, and felt more confident taking on the employer. Education also helped workers fight off the employer’s counterattacks. When management tried talking to workers one-on-one, Tanya says, “people saw through it.” Head office even came by, despite being absent for most of the pandemic. She says their stated reason for coming was, in their words, to help “promote a democratic vote among everyone.”

Nonetheless, the unionization campaign was successful. Joining UFCW Local 1006A, the location became the second dispensary in Hamilton to unionize, following Canna Cabana in 2020. The workers ratified their first contract back in December, tackling pay, scheduling concerns, sick days and more.

Asked what message she might send to other retail workers hungry for change, Tanya’s response is simple: “You’re the one making the boss money,” she says. “So do not be afraid. There’s strength in numbers.”

Tanya’s work will continue not just in her UFCW local, but in the UWW as well. Launched in Hamilton on April 20 (‘4/20’ as it’s known in cannabis circles), UWW strives to help workers “bring dignity” to the cannabis industry — and the organization’s website alone offers all that and more. It supplies a wealth of resources on health-and-safety protocols, migrant rights organizations, unionizing tips, refusing unsafe work and much more. Tanya personally hopes the organization will help transform the sector in a number of ways, namely by giving workers resources for organizing and promoting better material conditions, training and education. “It’s not just about legalizing it and regulating it,” she says. “We have that.” Tanya believes the priority now is shaping the cannabis space for the better.

UFCW Canada, for its part, has launched a new online outreach initiative called “Conscious Cannabis,” to help equip workers in the cannabis industry with resources “to achieve better wages and benefits and a safe, just and healthy workplace for all.” Its Conscious Cannabis website includes information about cannabis laws, the cannabis industry, health and safety on the job, and ways for workers to connect directly with the union if they have questions about unionizing.

A Matchstick Starts a Fire

At the same time, over 4,000 kilometres away, workers at Matchstick Coffee — a small specialty chain throughout Vancouver — were taking on a similar fight. A number of issues ignited the campaign. Low pay and lack of protections loomed large, particularly in light of the pandemic. The company had even received the federal wage subsidy, temporarily giving workers “hero pay,” then just as quickly taking it away — despite continuing to receive the subsidy. Management also failed to quickly establish COVID-19 protocols, which weren’t implemented until late summer 2020.

But even broader problems with management were brewing. In the summer of 2020, Matchstick’s co-owners, Spencer and Annie Viehweger, resigned following a deluge of allegations of abuse and toxic, often bizarre, behaviour. Recorded on an anonymously run Instagram account, posts submitted by Matchstick staff detailed numerous incidences of Spencer manipulating employees, wage theft, verbal assault, safety issues, incompetence and much more. The exposé was a lightning rod.

Ellie, a lead organizer and barista at Matchstick, recalls a conversation after work over drinks: “We all got together and thought, ‘Isn’t this crazy?’ And then unions got brought up. It all sort of snowballed from there.” The Viehweger controversy — combined with “emotions running high during the pandemic” and long-standing precariousness and mistreatment — became a lethal combo that led to a union drive.

A Campaign Amongst Chaos

A longtime employee, Ellie had strong relationships with a large part of her then 60-odd-person bargaining unit. Those deep connections allowed her to engage her co-workers in organizing conversations. Ellie was joined by a core of other women workers, who she describes as “really outspoken” labour activists. Initially, some of her male co-workers had been excited, but then “left all the women to organize stuff,” she says with a laugh. “I don’t think they realized how much actual work it’d be.”

Indeed, they had their work cut out for them. The whole process took around six months, the campaign itself amounting to half of that. Like workers in many workplaces, Ellie and her crew started mostly from scratch, having to entirely “reintroduce people to unionism,” and figure out ways — with the help of some UFCW training in having organizing conversations — to win people over.

Socializing ended up playing a major part in the campaign’s success. “It was a lot of texting with people, everyone meeting up for drinks in the park. [Unionizing] would come up all the time,” Ellie says. Organizers talked one-on-one to people about their concerns, convincing them in turn that a union could help. After three months, and a concerted effort to fight through the apathy and indifference of co-workers, it worked. Enough of Ellie’s co-workers signed cards to force a vote.

New Ownership

Matchstick, meanwhile, was going through a change at the top following the Viehwegers’ resignation. Wealthy new management arrived with a union drive on their hands. “I think it blindsided them,” Ellie says. “There was so much chaos that they didn’t notice this going on all this time.” Their response was severe, hiring “fancy, anti-union lawyers’’ to delay the process.

“They got really nitpicky,” Ellie says. Matchstick’s staff had shrunk in size during the pandemic, which the lawyers used to dispute the idea that the signed cards offered an accurate representation of how workers felt. Management also succeeded in disputing the eligibility of store managers — largely the more radical out of Matchstick’s workforce — to participate in the vote, despite those managers having no hiring or firing power (making them more akin to other employees). The new management continued the approach by promoting some of the more “hardcore campaigners” midway through the drive as well, thus disqualifying them from voting.

Slow Burn to Justice

The offensive helped Matchstick’s owners delay the vote for three months — but workers still voted 80 per cent in favour of unionization, joining UFCW 1518. Ellie attributes part of their success to the intensity of the circumstances and their own hard organizing work. She also heavily emphasizes that the vote was done online, which she believes contributed tremendously to the high turnout.

Following the certification success, bargaining for the first contract began. As a committee member, Ellie says that the process has been slow-going, focused mostly on basic issues around employment standards — not exactly the big plans they had hoped for. She says it’s been difficult to keep people engaged as bargaining drags on without immediate results. In this, her perspective is far from starry eyed. Rather, hers is an honest look by someone who played a central role in an arduous half-year campaign.

Nevertheless, with the campaign in the rearview, Ellie reflects positively on the situation. “Even if the process is slow, unions really have your back at the end of the day. It [made me] really confident to know that.

“Hospitality has some of the worst-treated staff,” she says. “There’s definitely a need for [unions].” Talking about the numerous other organizing drives in BC’s retail sector — including unionization at a Starbucks in Victoria, and at donut shop Cartems in Vancouver — she notes that COVID-19 “really launched people into campaigning.”

A tip she offers to other organizers or agitated workers: talk to one another. “It all came from talking about all [our] issues; that was the common theme across all of the cafes. Once people started to talk, and it was all out there — that was definitely the jumping-off point.

“Because then it’s like, ‘Oh, we can actually do something about this.’”

An Unfinished Story

Canada’s retail union wave highlights a radicalization among workers who have long been essential, but have rarely been treated like they are. Retail’s legacy of precarity and large-scale neglect by management has often been treated as normal, and therefore acceptable — but the pandemic transformed that legacy into kindling.

The contradictions of high profits and low pay, of high risk but no support, of big talk but no action — all cast against a global health crisis — became too much to bear for retail workers across the country. As union campaigns cropped up in response, new labour leaders were born — many of them women and racialized, those that have long borne the brunt of retail’s precarious status quo.

Taking full stock of Canada’s COVID-19 union wave, as yet, remains impossible. As this goes to press, vaccine rollout is in process, with many provinces beginning to open up but still braced for possible future waves; governments have still not legislated sick days (or they’ve provided too few days, too late) and essential workers continue clocking in while still waiting for full vaccine protection.

But there is an undeniable trend, a growing current underneath our daily diet of case counts and public-health press conferences, that shows workers coast to coast believe there is an alternative to the conditions they’ve been handed. And they believe they can win it themselves.

Sarah Nafisa Shahid is a freelance writer based in Toronto and a member of the Spring Socialist Network.

Dan Darrah is a writer, editor and member of the Spring Socialist Network. He lives in Toronto.