Slander is a crime that can have monetary repercussions. It would appear, though, that lying about the intentions of an organization you oppose has no such consequences. The smear campaign against unions by business, and some politicians, has been around since, well, before there even were unions; most of us have heard the stories from the late-1800s of companies hiring thugs to mercilessly beat workers struggling to unite for the first time. If you listen to all the right-wing rhetoric, you might start to wonder why we have unions at all. But, I can tell you, unions are not the scourge of the Earth. My life experiences have taught me the truth about unions: they are a blessing.

Back in my early 20s, I landed a job as an entry-level labourer in residential home construction. Management told me I'd be better off if I didn't join a union, since "archaic union seniority rules" would mean I'd have to stand in line for advancement behind more senior workers. I was young and a hard worker, and I believed them. I didn't join a union. Two years later, I was let go so the boss could hire one of his friends. This was my first lesson in unjust workplace practices.

I did find another job but at much lower pay, installing ventilation ducts in a new townhouse complex. I moved through a few other positions in the field, doing renovations, framing and customer service, but always with non-union construction companies. Not once was I told that, if I joined a union, the time I spent on each job would contribute to my seniority and eventually lead to more job security.

Frustrated with this lack of security, I eventually decided to seek work in another sector. Electronics was reported to be the next big industry, so I began working as a retail salesman at Radio Shack. I moved up to managing retail stores, but the hours were long and the pay unreliable, as it was dependent on sales.

A few years later a friend helped me land a job at Lear Seating, a unionized factory where car seats were made. I worked in the assembly area and my pay was enough to support my growing family, and provide opportunities for my two children that they wouldn't otherwise have had. My son was able to enrol in rep (competitive) hockey and baseball, and we could afford to pay for our daughter's college tuition.

At that point in my life I still knew little about unions, but my union rep did point out to me that, at this job, and because of the union, I could choose whether or not to work overtime. I no longer had to worry about being punished or even fired for not being available to work weekends. The next few years would provide me with a life-changing education about the need for workers' rights.

I worked at this job for just over a year before a slowdown in orders resulted in a group of us being laid off. I had access to unemployment insurance and, thanks to my union, a top-up was paid through my local. I was assured that, between future retirements and increased orders, I would be called back. This eventual recall was secure thanks to the contract bargained by my union representatives.

I could have sat back and waited for my recall, but that was just not me. I took training upgrades and soon landed a job at another factory. This plant was not unionized. It didn't take me long to learn several more hard lessons: employers can lie, and might not care whether you live or die.

The pay in this plant was based on piecework. But, try as I might, supply shortages and machinery breakdowns made it impossible for me to make enough parts to meet the production numbers that would translate into a reasonable hourly wage. I might have a couple of good hours, but then something would shut me down and I would be reduced to making minimum wage. During downtime I was still expected to work, cleaning out coolant tanks, removing metal shavings from the machines, or sweeping floors. However, no compensation was provided by the company for interruptions, even though these interruptions were no fault of the workers.

While talking to other longer-term employees, I learned that base-rate increases, promised to us upon being hired, were rarely, if ever, delivered, and never when promised. I also discovered that, while many of our working conditions were dangerous, employees were too afraid of being fired to say anything. We worked on raised platforms that had no fall-protection measures, such as railings. We were expected to push heavy carts over slippery concrete floors, each cart holding up to 20 transmission casings. Liquid chemicals, along with metal filings, ran into holding tanks that we were routinely required to clean out without the aid of a mask.

This experience provided me with a true understanding of the importance, for workers, of having the support and protection of a union. It angered me to see the older workers remain quiet and uncomplaining because of the threat of reprisal, while the younger workers unknowingly risked their health.

When an opportunity presented itself, I left to take another job, this one at a unionized factory where truck and car frames were made. Here, I worked as a machine operator in the stamping department. I operated the large metal stamping presses, which formed the components that would later be assembled to build the frames.

The work was hard but, again, thanks to the union, we were compensated with a fair and equitable pay package. Our union worked with management to make sure the workplace was safe, and workers didn't have to worry about unfair treatment from a supervisor just because he or she didn't like you, or was having a bad day. If any of us had a complaint, we could speak out and be heard without the risk of being fired.

We had job ownership, which meant that if your press was running, you were guaranteed to be assigned to that job. Thanks to the union, the company couldn't arbitrarily move you to another machine — perhaps one that paid less per piece. If an easier, or better-paying, position became available, you could submit your name, and the person with the highest seniority would get, and now own, the job.

Having a union meant that the movement between jobs was accommodated in a fair manner, based on seniority. Everyone had an equal opportunity. If you didn't get a posting the first time around, eventually, your time would come.

But this was not the most important gift that the union gave me.

By now I recognized the enormous benefits of being unionized, and so I strived to learn more about my union. I started to attend union meetings, something that, unfortunately, too few members do. I learned that my voice mattered. A union operates as a democratic entity, and every member has a stake and a say in its direction and priorities.

I eagerly became more knowledgeable about, and more involved with, my union's activities. The Christmas parties and Easter egg hunts put on for the members' children warmed my heart. Socials, such as birthday and retirement parties, were all held at our local hall and every member had access to the facilities because they all helped pay for them. There was a summer baseball league, too.

Eventually, I volunteered to represent my local as a delegate at the Waterloo Regional Labour Council. Thankfully, my application was accepted by the members. This experience brought about a sea-change in my views about labour, the workforce in general, and the pressures inflicted upon workplaces by global economic forces.

One of my early campaigns as a labour council representative was to help raise public awareness about the need to raise the minimum wage, and to pressure the Ontario government to do so. In 1995, the minimum wage was frozen by the Conservative government of Mike Harris. Because of this, real purchasing power for Ontario's poorest workers had decreased 20 per cent by 2004. After the Conservative government was defeated, we took to the streets, parks, and MPs' offices to push for a change. Finally, in 2007, the Liberal government pledged to raise the minimum wage to $10.25 by 2010.

People deserved more, but this was at least a partial victory for some of the most vulnerable workers. I felt satisfaction in having been a part of this, but it wasn't until 2011 that I really understood the impact the campaign had. I was participating in a training exercise at a local employment agency (I was once again among the unemployed), where we were asked to talk about something we were proud of accomplishing. I talked about my involvement in the campaign to raise the minimum wage.

After I finished talking, a young woman came up to me and thanked me. She explained that she had been a single mother at the time, struggling to raise her young daughter on her own. She still remembered how every penny of the increase went towards making their lives better.

I remember the first time my wife came with me to a conference at the CAW Family Education Centre, in Port Elgin, Ontario. A group of newly organized personal support workers went to the front of the stage and explained to the rest of us how much better their workplace was now that they had the union's support. No longer did they feel afraid. Instead, they felt empowered, and enjoyed going to their jobs. Later, my wife told me she could hear the pride in these workers' voices, thanks to their newfound strength. She also told me she had not previously been aware of all the social justice work that unions did.

Being part of a union both enriched my life and empowered me. Being part of a group of dedicated people inspired me to believe there is a better way.

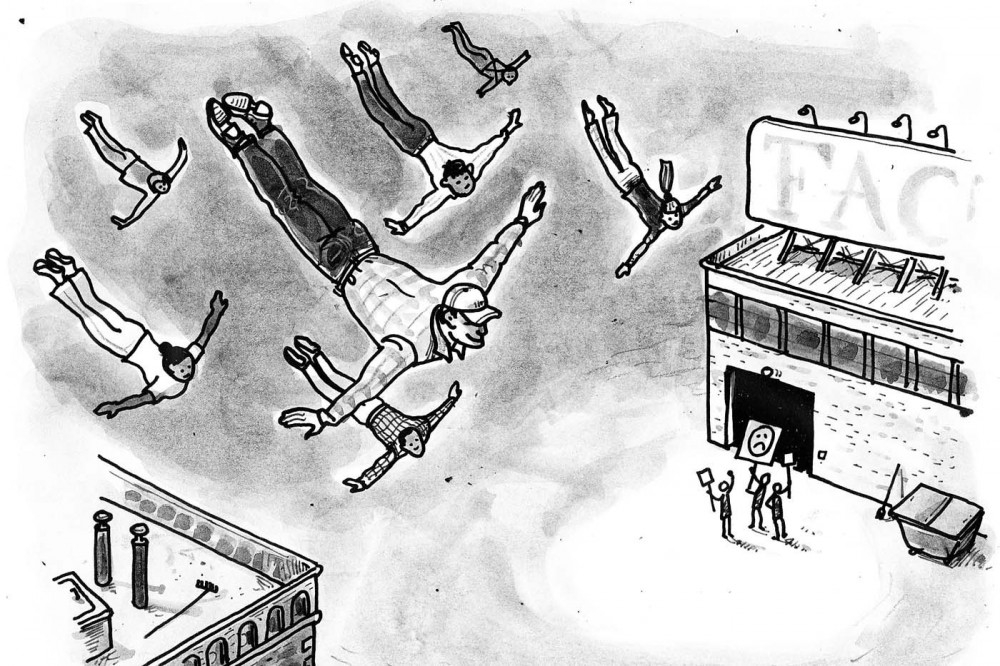

Within my union, one such group was the "Flying Squad," which I had the privilege of helping build in our area. This unselfish band of brothers and sisters volunteered their time to stand with other workers in need of a hand. With a simple phone call or email, we would get organized and "fly" to wherever our help was needed. We drove to Windsor to support a group of taxi drivers asking for fairer compensation and safer working conditions. We went to Sudbury to march with mine workers resisting concessions being demanded by the rich corporate mine owners. We went to Quebec City to add our voice to concerns around globalized trade pacts.

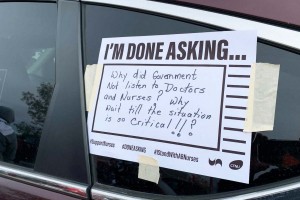

One of the more heartwarming adventures we had was joining a small group of women striking the nursing home they worked at. Because their work was classified as essential, they couldn't all be out on the picket line at the same time. These women had to complete their shifts, then show their support for their co-workers on the picket line, and still find time to sleep and look after their families. It was extremely difficult for them to juggle so many responsibilities. So, our group, along with other flying squads, got organized and offered additional bodies, on a rotating basis, to help bolster their picket line. Within a week of our members joining with these workers, the employer agreed to settle the outstanding issues.

The women thanked us profusely and said they felt the settlement would never have been reached so quickly, and satisfactorily, without our support.

I felt a similar sense of gratification when we supported a handful of workers at an automotive dealership. There was no way, with their small numbers, that they could effectively demonstrate in front of their workplace. With the help of our leadership, flying squads managed to disrupt the business enough to get the owner's attention. Again, this strike ended quickly, and successfully, because of the generosity of union brothers and sisters, volunteering their time on behalf of others.

So, what was the most important gift unions gave me? An opportunity to help others more disadvantaged than myself. To feel my heart bursting in my chest when given warm accolades from truly thankful people. The acknowledgement that I made a difference. Still, we did it for no other reason than it was the right thing to do.

I urge all those touched by the benefits of a union's actions to speak up against all the slanderous misconceptions about unions being touted by those who hope to benefit from weakened unionization. It seems times have changed very little from the 1800s. Workers need to stand up and shout down the corporate powers and their political lapdogs before the gains of the past are lost and we stand alone.

This story is the latest instalment in one of Our Times' longest-running and best-loved series, Working for a Living. Our Times has long believed that in telling our stories, we workers strengthen the movement, and each other, with every word. Please join us in making our voices even stronger by sharing your story. Writing may be something you truly adore or something you've never really tried before — either way, we'd love to hear from you.

Doug Butler lives in St. Thomas, Ontario. While no longer officially affiliated with a union, he attends the local labour council meetings as a community member, and represents the council on several boards, including the United Way's. "Even today," he says, "while unemployed due to the closure of my workplace, I am still active, through my local labour council, and committed to fighting for labour and social justice."