It's a Monday evening at Kwacha House Café in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The clientele may be gone for the day, but the conversation is just beginning. Three members of the Working While Black in Nova Scotia project have gotten together to explain what the project is and why it's needed. Matthew Byard is co-chair of Ujamaa, which he describes as "a political action network that lobbies and works on behalf of the Black community in Nova Scotia." Folami Jones introduces herself as a community activist and the owner of Kwacha House Café, a café tuned in to "social inequities in the broader community and its effects on the African Nova Scotian community." Ben Sichel is a Halifax-area high school teacher and a member of Solidarity Halifax's anti-racism committee.

Together with other Working While Black in Nova Scotia (WWB in NS) project members and numerous anonymous storytellers, they have created an online space that confronts a persistent and infuriating myth: namely, that racism is no longer a problem in this province.

"Working While Black in Nova Scotia is a web-based project that is documenting anti-Black racism in the workplace in Nova Scotia," says Sichel. "It's a collaboration between three organizations, which are Solidarity Halifax, Kwacha House Café and Ujamaa."

Endlessly defining and redefining racism can hamper conversation about real experiences. For this reason, the WWB in NS website allows participants to directly submit writing about real-life encounters with racial oppression, rather than making them first prove their experiences are somehow "racist enough" to include.

"I guess everybody has their own opinion as to what it is, so myself, personally, I try not to get bogged down on trying to say 'Is that racism?' or 'Is that not racism?'" offers Byard. "I'm more interested in whether something is wrong or just. I'm more interested in whether something is discriminatory or prejudiced against people of a certain race." The Halifax resident is concerned about the invisibility of much everyday racism, and the notion that "real" racism is only its most extreme manifestations.

"I don't know that it's necessarily most, but I think a lot of white people equate racism with images of very vicious racial hatred, stuff we saw in the U.S. in decades past like the Ku Klux Klan, lynching, things that are depicted in films. So I think in a lot of people's minds, the absence of that means the absence of racism. Whereas to people who experience racism, particularly people of African descent, something very small can still be racist. Now, somebody may say, 'Oh, it's not racist, because they just didn't want to serve you at that restaurant.' Well, it may not be a big deal, but I still define it as racism, because that sort of thing's wrong."

Folami Jones adds that the scope of WWB in NS had to be refined because there are so many forms of discriminatory behaviour.

"One of the things that comes to mind for me, in terms of racism, is how it works in so many different ways," she points out. "How it can manifest and expose itself in systemic ways, institutional ways: overt racism, internalized racism. And there's lots of discussion on how racism is constructed.

There's a larger discussion, but I think for the sake of the project, we're looking at the experiences of prejudice and discrimination, forms of oppression, against African Canadians who are living in Nova Scotia, while they're looking for employment or while working in their own field of employment."

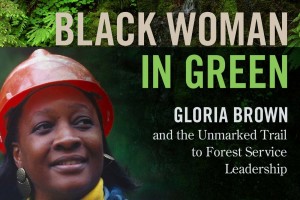

From left to right: Ben Sichel, Matthew Byard and Folami Jones are all involved in the WWB in NS project. Matthew Byard is co-chair of Ujamaa, a political action network that works on behalf of the Black community in Nova Scotia.

Tightening the focus may seem counterintuitive when solidarity is the objective. But Byard notes that among racialized groups in North America, people of African descent are still subjected to a very particular kind of pigeonholing. "One of the things that I find that you learn, that I heard about at school, is the concept of 'black inferiority,' which I think is very vast. It stems, I think, from when explorers first 'discovered' Africa, and what you had was word-of-mouth about these 'crazy beings,' 'wild beasts' and things like that."

Centuries later, he finds that this stereotype lingers, in part because Black people constitute one of the largest minority groups in Nova Scotia and North America. And mainstream culture reinforces the idea. "I find there's a lot of stuff, in the media, in art, places like that, that reiterates this idea of black inferiority. Many people see Black people as less capable or less trustworthy or more likely to cause harm, and things like that, and we buy into it. Whites will buy into it and Blacks buy into it as well, and it manifests in the way we interact with people."

Ben Sichel says discussions with fellow WWB in NS founding member Carolann Wright-Parks helped clarify the need for a project about workplace-related racism directed toward African Nova Scotians. "It's not that we're saying anti-Black racism is worse or necessarily more prevalent — it's just different. And one thing when you start to learn about different racisms, you realize they are different — anti-Aboriginal racism is different from anti-Black racism is different from racism against people of South Asian descent, East Asian descent," he observes. "The stereotypes are different; the expectations placed on people are different, and the history of African people in Canada and Nova Scotia is a particular history" — a history marred by the shameful treatment of Black Nova Scotian workers.

"Capitalism was built on colonial dispossession of Indigenous people, and dehumanization of people of African descent. I mean, how do you steal 12 million people from a land and force them into chattel slavery, if you don't view them as subhuman?" asks Sichel. "The whole wealth of North and South America and Europe was built on colonial racism, on treating people as subhuman, exploiting them for their labour, and that has gone on since those days."

The local teacher and activist says Nova Scotia law considered Black people "a source of cheap labour in the 1700s and 1800s," so when these underpaid workers competed with whites for the same jobs, hostilities flared up in a depressing piece of Nova Scotian labour history.

"It's a little-known fact that the first so-called 'race riot' was here in Nova Scotia, in the small town of Shelburne, in 1784, because desperate Black workers were willing to work for lower wages than white workers."

Jones remembers her father telling her as a child that the overt racism she experienced was, sadly, nothing new. "When I would speak to my father about some of those struggles, he would speak to his struggles and his grandmother's struggles and his great-grandmother's struggles. And so, all to say the experience of racism in Nova Scotia is old," says the daughter of legendary civil rights activist and lawyer Burnley "Rocky" Jones (1941–2013).

"It's very long, and thus the struggle has been very long, and being one of the oldest Black communities in North America, that history comes with very different pains and resistance as well. I just was thinking around how old that history is recently, with some of the stories we hear from newcomers — those same stories I heard my father talking about, we're still talking about some of those same things." African Nova Scotians and allies are also turning to the WWB in NS website as a safe place to highlight the ongoing nature of those painful experiences.

The Kwacha House Café is located at 3450 Dutch Village Road, in the Fairview community of Halifax.

Nova Scotia has a past in which Black workers were promised much, but given little.

"Black communities have been in Nova Scotia since the 1780s, refugees from the Revolutionary War in the United States and then later from the War of 1812," explains Sichel. "And from the moment that Black people came here, to escape from slavery and fight on the British side in the war, they came here and found out freedom wasn't all it was cracked up to be in Nova Scotia. They called us 'the Mississippi of the North' up here for a reason: they were given the worst land or not given the allotments they were promised in terms of land and provisions, one thing after another, and that legacy has been passed down to the present day."

Byard adds that Black Loyalists in this province expected freedom and equality when they agreed to fight with the British in the American Revolutionary War, but ended up "at the bottom of the list" for land grants afterwards.

Being treated like second-class citizens on the basis of ethnic background and/or skin colour continues to harm people at work, in physical and psychological ways. He says his father, now in his late 60s, remembers the blatant message of integrated schools with racially segregated bathrooms.

"Teachers would be more harsh, more stern, with the Black students," Byard's father told him. The segregation even extended into houses of worship: "I can remember my aunt was telling me about something going on at 'the Black church.' It was on a Wednesday night. I was sort of joking with her about going to church on a Wednesday night, and she said 'Back in those days, you didn't go when you wanted — you'd go when you were welcome.'" African Nova Scotians internalized the discouraging message.

Creating a way to externalize and share experiences of workplace racism in Nova Scotia was an objective at the early WWB in NS meetings, which came out of a series of Ujamaa sessions dubbed the "Dialogue Lounge."

Byard brings up Garnetta Crowell, a Black saleswoman invited by Ujamaa to speak at one Dialogue Lounge. In April 2014, Cromwell won a Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission complaint filed against her employer, Leon's Furniture, for a series of racist incidents she experienced in early 2008 while working there. The discrimination culminated in her supervisor referring to her performance review meeting as a "lynching." Before she won the case, Cromwell's car was vandalized, "nigger" spray-painted on its side.

"The idea for Working While Black came from those discussions," Byard tells Our Times. "People really wanted to discuss those sorts of things — 20, 30, 40 people in a room, sitting around and discussing their experiences."

Solidarity Halifax was approached by Ujamaa, adds Sichel, about expanding upon the Dialogue Lounge sessions. "Listen, we have these discussions in the Black community, everybody knows it's happening, but we're not getting any publicity, so can you guys get out the word, beyond the Black community?" he says, quoting Carolann Wright-Parks.

The WWB in NS website followed, as a way to amplify the voice of African Nova Scotian workers and allies. "Outside of the Black community, it would allow people to see, hey — this is still happening in 2015," Sichel explains.

Ben Sichel is a Halifax-area high school teacher and a member of Solidarity Halifax’s anti-racism committee.

Logistics were figured out over the course of numerous meetings. "It all came down to six or eight people sitting in a room together, talking about the best way to make this happen, and then we were preparing for a launch that was supposed to happen a couple of months down the road." But buzz on social media led to unexpected early publicity. Stephanie Domet, the host of CBC's Mainstreet Nova Scotia "saw the website and asked us to come in. People started sending stories in from there."

Why are the Dialogue Lounge and the Working While Black website both so popular? Undoubtedly, in part because African Nova Scotian workers can speak out and be heard, without having to soften their stories for the approval of anyone else.

"We hear about this thing called 'the race card,'" sighs Byard, an activist familiar with the many ways in which Black experiences are written off. "'Oh, that's not racist — you're just overly sensitive!' or 'How can you prove it?' or 'How do you know for sure?' When you're Black and you've lived for a certain amount of time, sometimes you don't have the willingness or energy to try to explain it to someone to prove your point. But when we get among ourselves, we're in a more comfortable space to discuss that sort of thing, to be more specific."

WWB in NS curates its content based on meetings among members. "One of the great things I love about this project is the collective ideas that come and the discussions that happen," says Jones. "There are some really dynamic people that sit around this table and have some of those difficult conversations, and sometimes we even get lost in the night, trying to work out those small things, because there's a lot of detail, like for example if someone submits a story — how do we edit the story?" Also critical is "making sure that the power dynamics are open and transparent and that there's a lot of leadership coming from the African Nova Scotian community."

Comments, it should be noted, are not permitted on the WWB in NS site itself, although some of its stories have now migrated to Facebook as well. Sichel says allowing readers to comment alongside the submissions was deemed unnecessary. "There's plenty of places on the internet to do that, and we wanted a place where Black people's stories could stand on their own."

Allies can also contribute to WWB in NS, either by helping someone submit their anonymous account of experiencing anti-Black racism, or by submitting their own account of witnessing anti-Black racism.

"Who's participating in this project and in what capacity? Who's leading it? Whose responsibility is it to expose anti-Black racism in the workplace?" asks Sichel, stressing that it's not just African Canadians who should be speaking up about offensive treatment of Black workers.

The Kwacha House Café is a warm and safe space for political dialogue — plus it serves great food.

Asked to characterize the stories they've received so far, Byard calls them "upsetting." Jones uses the word "bittersweet" — she appreciates the sharing of Black experiences, albeit ones that non-Black Nova Scotians frequently equate with the distant past or with the United States.

Both she and Byard agree that the stories on WWB in NS are highly relatable. Jones mentions one titled "I'm Not Your Mammy" about "a lady from Jamaica who was working as a health-care aide, and one of her clients insisted she was the lady from The Book of Negroes, from a magazine, and that she was famous and that was her. Even though she had been with this client for a very long time and had history with her, you know, the client insisted that the picture of the slave was her. Part of it was obvious, that the client was relating the role of the 'mammy' and the role of the personal caregiver."

If such experiences are mind-boggling to read about in 2015, the overall persistence of anti-Black sentiment in her home province is less so, states Jones. "The things that people say and do, they would surprise you — but not really."

Even Jones' cozy west end café has not been entirely safe from presuppositions about Black inferiority. Recently, two well-meaning white customers at Kwacha House Café engaged her in a conversation which quickly turned into a strange appraisal.

"For some reason, they started talking about the café, about 'Wow, how cool it is!' and how their sons could come here all by themselves," recalls the still-incredulous business owner. "One of the women said, 'My son is so brave, he can come here all by himself.' And I remember looking at her, feeling this anger, like 'What did you think? That the café is like this corner full of guns and violence? Why would it be such a big deal for you to come to the café that you needed your friend to come?'"

When the women admired the café's Afrocentric décor, they spoke as if a flabbergasted Jones was herself part of the scenery. "She exotified me! I was sitting there and she's literally telling her friend, 'Look at the girl — look at her!'" recalls Jones. "They were almost dare-devilling themselves to come into the café."

WWB in NS is not a project restricted to the internet. It functions as more of an intersection, where real-life accounts of racism are documented and greater real-world awareness of racism follows. In terms of employment, "when you ask the people who submit their stories, what did they do or have they been able to address them with their employer, most of them say, 'Are you crazy? I'll lose my job!'" notes Jones, adding that WWB in NS members are looking at how they can make their project even more of a community resource. "We're hoping to find ways to support the people with those stories, if they want to take it further, but a lot of times, people aren't even able to share it," she says, "because can you afford to lose your job? Can you afford to expose to people, that you don't trust in your office or place of employment?"

Folami Jones at The Kwacha House Café.

Becoming a whistleblower about racism at work can indeed compromise job security, agrees Sichel. "If you're walking down the street and someone acts towards you in a racist way, it can ruin your day, it can affect you emotionally, but it doesn't necessarily affect you materially. In a workplace, because we all have to work because we live in a capitalist system where we have to sell our labour to survive, you know, you've got to do what the boss says a lot of times. So workplace racism is a very impactful sort of racism."

The most recent statistics available from the Nova Scotia Department of African Nova Scotian Affairs echo that assessment: in 2011, 14.5 per cent of African Nova Scotians were unemployed, as compared to 9.9 per cent of all Nova Scotians and 12.9 per cent of African Canadians across the country. African Nova Scotian men were hit especially hard, with 17.2 per cent unemployment.

Provincial wages were also considerably lower for this demographic, as Black men and women averaged $29,837 and $24,929 respectively. The overall average incomes for Nova Scotians were $42,545 (men) and $29,460 (women).

There is no information about how many African Nova Scotians belong to unions, although the above statistics on wages suggest the number is not high.

And statistics don't tell the full story. Shaking his head, Byard recounts an absurd comment made by New Brunswick MP John Williamson as recently as March 2015, regarding the Temporary Foreign Worker Program.

"Williamson said something like 'it makes no sense to pay whities to stay home while we bring in brown people to work in these jobs.' Again," points out Byard, "this is just the same kind of rhetoric."

Only now, the Working While Black in Nova Scotia project is emerging as a force against such racist rhetoric. It is steadily gathering voices, voices which are making it clear that in Nova Scotia and beyond, anti-Black words and actions have no place.

To read or contribute a story to the WWB in NS project, visit Working While Black in Nova Scotia. .

This is just a sample of the kind of articles you'll find in Our Times. For more articles like this, plus commentaries, poetry and reviews, subscribe to Our Times.

Support Our Times.

Melissa Keith is a former radio broadcaster and an award-winning freelance journalist. She lives in Lower Sackville, Nova Scotia.