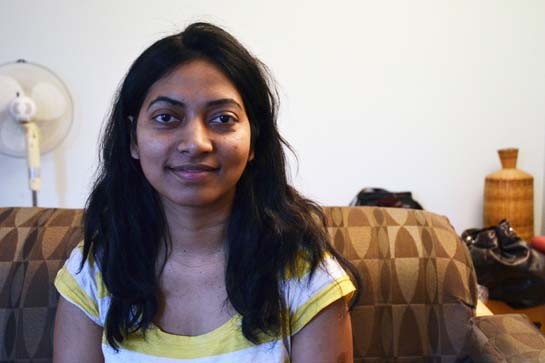

Leticia Ama Boahen

The fight for workers' rights has a long and celebrated history in Toronto, as does the Mayworks Festival of Working People and the Arts, now in its 29th year. This year, Toronto's festival included a panel discussion, "The Struggle For Economic Justice," about the campaign to raise Ontario's minimum wage, as well as Ontario Works and Ontario Disability Support Program rates.

The panel was about issues of poverty, as a whole, and how they affect racialized immigrants and working people in general. The speakers were Leticia Ama Boahen and Suzanne Narain of Toronto's Jane-Finch community; Kaydeen Bankasingh, from the Lawrence Heights and Neptune communities; and Sonia Singh from the Workers' Action Centre (WAC), a grassroots organization committed to improving the lives and working conditions of people in low-wage and unstable employment. Acsana Fernando, also from the Workers' Action Centre, couldn't take part in the panel but agreed to speak with Our Times.

Amid work, school, long commutes, child care, and organizing meetings, these five women took the time to share with Our Times the stories of their families, their communities and their collectives.

Listening to these leaders from some of the Greater Toronto Area's most disenfranchised communities taught me a lesson in the realities of marginalization, but also in the amazing work being done to challenge it.

I learned that we are surrounded by some of the most dedicated, resolute and unwavering organizers anywhere. Your neighbours, your fellow commuters and the people serving you your morning coffee are using their free time to fight for all of us, and they share a common message: give us a living wage and let us live in dignity.

RESIDENTS RISING

I met Leticia Ama Boahen at the Jane/Sheppard public library. A former community development worker with the Jane-Finch Community and Family Centre, Boahen now works at Everdale Farms, a teaching farm that provides hands-on food and farming education to help build healthy local communities. She has lived in the Jane-Finch community since coming to Canada from Ghana in 1996.

In 2008, she joined the newly formed Jane Finch Action Against Poverty collective, which describes itself as "a resident-led grassroots coalition of residents, activists, workers and organizations working to eliminate poverty in our community and in the world."

Jane-Finch community members have been struggling for years to end poverty, most recently through the campaign to raise the province's minimum wage to $14, spearheaded by the Workers' Action Centre.

In Ontario, the minimum wage has been frozen at $10.25 for three years. The Raise the Minimum Wage campaign is asking for the minimum wage to be raised to $14 an hour, and for a commitment to annual cost-of-living adjustments. The campaign's assumption is "No one should work full time and yet still live in poverty."

A DIGNIFIED LIFE

"We're asking for $14, which is not really a lot; it only brings you just above the poverty line," Boahen says. "Raising the minimum wage is really about giving families a chance, you know? To give them that opportunity to live in dignity. They work for it, they deserve it. We need $14 now for families to just make ends meet."

As a community volunteer and a mother of two, Boahen has helped put together Mothers in Motion Fitness, a free "mums-led" fitness program that provides child care and a flexible schedule to fit participants' hectic lives. "It makes fitness accessible for low-income families," says Boahen.

The International Day for the Eradication of Poverty is celebrated on October 17 throughout the world. On that day in 2008, Jane Finch Action Against Poverty was born, with volunteers organizing one of the biggest rallies in the community since the early '90s. With that, they brought the community together and began a shift towards de-stigmatizing the Jane-Finch neighbourhood and standing up for the needs, and rights, of the community.

"This is our lives," Boahen says, about the work done by JFAAP volunteers. "We've taken it on to challenge the system and we need a lot of support in order to do that, because everyone is doing it on their own time."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A four-year JFAAP member and lifelong Jane-Finch resident, Suzanne Narain works as an elementary school teacher in the same community that she grew up in. She's watched her community grow, and seen difficulties develop for families as the cost of living increased while wages stayed low.

"Poverty is not just reserved for people living in community housing," she says. "Rather, there is poverty in all communities, and the face of poverty is changing. It particularly plagues immigrant communities."

In a city like Toronto, where half the population was born outside of Canada, understanding the experience of immigrant communities dealing with poverty is essential for understanding and combating poverty in the city, and the province overall.

Suzanne Narain

Narain's parents arrived from Guyana in the late '70s and eventually settled down in the Jane-Finch area. "I think a lot of immigrants want to have this better life, and a better life means having a home. So, they do get a home, but then at least 75 per cent of their income goes towards paying a mortgage, or buying groceries." Narain says JFAAP supports the campaign to raise the minimum wage "because we believe $14 is a living wage in Toronto and Ontario."

Narain's parents both worked as custodians to support her family, and they are still working.

"They worked seven days a week for my entire life," she says. "I definitely understand what it means to work hard, and for families to have to sacrifice a lot in order to make ends meet, in order to provide food and shelter for their families," Narain shared with me before a JFAAP meeting in late March. "A lot of families, especially in the Jane-Finch community, are working three jobs just to make ends meet. Raising the minimum wage will help alleviate some of their stress."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

"We just survive; this is just survival," is what Kaydeen Bankasingh, Lawrence Heights/Neptune resident and community leader says to me when we meet for coffee in the neighbourhood she now calls her home. "I always felt that it was such a vibrant, bright place," she says. "What I saw wasn't what other people around me were seeing."

Lawrence Heights, Neptune and Lotherton Pathway are three neighbourhoods often referred to, together, as Lawrence Heights. The first large public housing project built by Metropolitan Toronto outside of the then-city of Toronto, it is now managed by Toronto Community Housing (TCH). A community often misrepresented in the media as having a penchant for gang violence, its residents live in TCH units near the very affluent Lawrence Park neighbourhood.

Lawrence Heights has been undergoing a city-endorsed neighbourhood revitalization, which was supposed to focus on building community structures; replacing old subsidized housing with newer units; and expanding green spaces, among other changes.

Kaydeen Bankasingh

At the same time, says Bankasingh, "our councillor recommended that we start some kind of residents' committee, a residents' group that could proactively start to do some community development work." And so the Neptune Renewal Group was born. Known as eNeRGy, it's building a valuable network amongst residents, with different programs, events and safety initiatives.

In 2010, the group was given a community safety award for their work planning social events and developing solutions and ideas to help make their neighbourhood healthy, clean and safe.

They recently launched a youth council and established a youth lounge in an effort to create community spaces for leisure, study and dialogue.

Over half of the LawrenceHeights/Neptune/Lotherton residents are under the age of 24 and youth underemployment is a big issue. According to Bankasingh, some employers will shy away from job applicants with Lawrence Heights addresses, assuming they might cause trouble or allow their friends to steal. Those youth lucky enough to have found work may have, during their job search, listed alternate home addresses in order to avoid being stigmatized.

Despite her role with eNeRGy, Bankasingh doesn't consider herself an activist in the traditional sense. "I'm a resident first," she says, "We are resident leaders. If activism means being able to speak out and say: 'These are the challenges and realities of families and children and youth and seniors living in the communities and having to survive and meet their basic needs,' then, yeah, I'm an activist."

THE GENTRIFICATION OF FOOD

Like many neighbourhoods in Toronto undergoing development and dealing with gentrification, Lawrence Heights residents' day-to-day living is being affected by intra-neighbourhood politics. Says Bankasingh: "Residents have to deal with the impact of being displaced from their homes, having to live in and amongst a high-income neighbourhood. We have to deal with that reality, while not having enough to provide for our families."

With a minimum wage that keeps people below the poverty line, being able to meet basic needs becomes incredibly difficult, especially for those, like Bankasingh, who are providing for a family.

"In the last 10 years, since I've been grocery shopping and feeding my family independently, I've watched the price of basic groceries increase by almost 300 per cent. Everything is getting more expensive. There is no question in my mind that our incomes should keep up with inflation."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Acsana Fernando doesn't get much sleep. She goes to school full time during the day and does the graveyard shift as a support worker in group homes for physically and developmentally disabled residents.

She spends hours on public transit getting to and from work and, as she told the CBC's The Current, in January, she can't afford to buy a monthly bus pass and so must struggle to find money for transit tokens. "A token is almost like gold to me."

She is also a community leader and organizer with the Workers' Action Centre. Fernando arrived in Toronto in 2002 from Bangladesh and found out about the Workers' Action Centre through one of their English as a Second Language (ESL) workshops.

At the time, she didn't know what labour rights activism looked like in Canada, but, since then, she's become a regular volunteer and community organizer with WAC. "It's a great organization for people who don't know their rights or don't have a voice," Fernando says. "WAC is working on behalf of them. And as a citizen, as a community member, we should all take part."

Acsana Fernando

In her capacity as community organizer, Fernando has participated in almost all of the monthly actions held by the centre for the Campaign to Raise the Minimum Wage. She also supports WAC members, and members of her own community, by investigating stories of unfair wages and employment scams, and by sharing her knowledge with her neighbours and colleagues.

Fernando supports herself as well as her father and her brother, both of whom are chronically ill and unable to work. With Fernando as the sole breadwinner, her family often has to rely on local food banks, with available food fluctuating day to day.

Two hours waiting in line at the food bank in Scarborough means Fernando might miss a day of school or a work shift, and it won't even guarantee her any food to bring home to her family.

CHANGE IS NEEDED NOW

"It's not only me," she says. "There are lots of people I know who are struggling in this neighbourhood. My struggle is everybody's story."

Trips to the food bank, taking her father and brother to doctors' appointments, and her long school and work hours afford Acsana no leisure time. Yet, she still finds time to volunteer with the Workers' Action Centre. "I have to, for those people who did it when I first came. As a newcomer, I didn't know, but there were people fighting. So, I have to keep doing it."

When I met with her in March to talk about leadership and activism, she had a sprained ankle. Despite this, she travelled hours to meet me to share her story and to tell me about the work WAC is doing. "It's an organization that gives people hope," she said. "This is the time that we have to speak out. We need the change immediately; we can't wait anymore."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Sonia Singh has been organizing with the Workers' Action Centre for over 10 years. A Toronto native, she grew up in the Woodbine and Gerrard area in the east end of Toronto, and came to WAC through a volunteer collective called Justice for Migrant Workers.

When we met at the WAC office in downtown Toronto, she explained to me the connection between workers' rights and immigration issues. "Status completely shapes what your experience is like in Canada," says Singh "Not only are you working in low-wage, often difficult and dangerous work, but your access to so many other things is limited. We need to have an equity focus both in the way that we talk about the changes we want to see, the demands that we're making, and the kinds of alliances that we're building through our work."

WAC is a member of the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change (MWAC), a coalition of migrant worker groups and allies.

Partly in response to news about the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, the coalition recently posted a statement online titled "We need to change the conversation from exclusion to creating good jobs for all."

Sonia Singh

As a full-time staff member at WAC, Singh has also been part of the monthly actions that have taken place since the Raise the Minimum Wage campaign was launched on March 21, 2013. Ever creative, organizers kicked off the campaign by getting community members to present blocks of ice to MPPs, to encourage Queen's Park to "melt the freeze" on the minimum wage.

"On a personal note, it's really exciting to be part of something that you see growing," Singh says. "We know what we need in order to have access to better working conditions and better jobs in Ontario."

At presstime the Liberal government had committed to raising the minimum wage to $11 an hour, starting June 1, and a promise was made to index minimum wage to inflation.

As one of the demands made by the WAC campaign, the 75-cent increase was a small but important victory. However, it's important to stay true to the ultimate goal of $14 an hour, since $11 an hour is still 16 per cent below the poverty line.

"Eleven dollars is not going to get people what we are fighting for," says Singh, "which is to be working with a little bit of dignity, and to be living above the poverty line. It's not an impossible dream; it's something we can achieve, working together."

The Mayworks panel "The Struggle For Economic Justice" was co-presented by Jane Finch Action Against Poverty and West-Side Arts Hub, and co-sponsored by the Workers' Action Centre and the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP). Food, transit tokens and child care were provided.

Haseena Manek is an Ottawa-based labour journalist, and Our Times’ Online Community and Outreach Coordinator. Follow her on Twitter here.