When Sahra Kaahiye became the first person in her province to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the Edmonton respiratory therapist felt a rare moment of relief. Working conditions have been grueling, hazardous and unpredictable for many workers during the pandemic’s second wave, taking an enormous toll on frontline healthcare workers in particular.

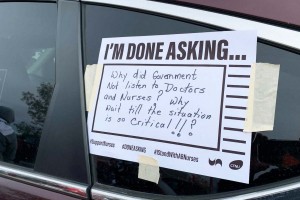

“I’m sure you might know that there’s been tension between some doctors and the provincial government,” says the Health Sciences Association of Alberta (HSAA) member. “We’ve unfortunately had a lot of uncertainty regarding our doctors. We’ve had a lot of doctors leave, and the number of doctors we’ve had rotate through our unit has also declined. The ones who are currently there can’t tell us if they are going to stay.”

In 2019, Premier Jason Kenney’s United Conservative (UCP) government began drawing a blueprint for cuts to public healthcare. To justify increased privatization, they used two reports: the MacKinnon report, which was released by the Blue Ribbon Panel on Alberta’s Finances (2019), headed by former Saskatchewan finance minister Janice MacKinnon; and the $2-million Alberta Health Services Review (2020), commissioned from multinational consulting firm Ernst and Young.

Framed as trimming fat from provincial spending, recommendations leaned heavily in favour of diverting funding from the $20.6 billion allocated for healthcare in last year’s budget. As Sammy Hudes and Dylan Short outlined in the September 10, 2020 Edmonton Journal, $5.2 billion of that budget had been earmarked for doctors, which Health Minister Tyler Shandro found unacceptable. The Alberta Medical Association could not agree to drastic cuts to physicians’ services and fees proposed by Shandro in February of 2020. Then COVID-19 struck, forcing the UCP government to hit “pause.”

Respiratory therapist Sahra Kaahiye was the first person in Alberta to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. She is a member of the Health Sciences Association of Alberta (HSAA). PHOTOGRAPH: NUURA MOHAMOUD

Suddenly, doctors and other workers in essential jobs were being called “heroes.” Kaahiye describes the arduous workplace conditions created by the pandemic: To guard against COVID-19, “We do regular swabbing; I get swabbed once or twice a week. If it comes out that there is an asymptomatic positive, we end up having to do a whole other round of swabbing, and swabbing the patients as well. That staff member who is asymptomatic has to stay home and quarantine,” as must co-workers who exhibit any of the vague, varied signs and symptoms of the novel coronavirus. Because of all these factors, “there is always such a shortage and shuffling of staff members. I know it’s something that management really struggles with.”

The struggle with “working short” is very real on the frontline of Alberta healthcare. “There are times where we’re down to just a handful of nurses on the unit, and only one RN who’s in charge, or they’re scrambling trying to get a casual to come in, or lots of overtime to get people to stay overnight,” says the respiratory therapist, who divides her time between the respiratory unit at CapitalCare Norwood and Glenrose Rehabilitation Hospital. “I know myself, and a lot of people not just in respiratory but in nursing fields as well, everybody is just trying to do their best to pick up as many shifts as they can. But they’re getting really tired.”

Tired of the pandemic, tired of 16-to-24-hour shifts, and tired of being called “heroes” while the government looks for ways to take away their jobs — and make sweeping cuts to public healthcare: All of the above apply for Susan Slade. She’s a licensed practical nurse (LPN) who is currently working full time with the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees (AUPE), and was elected one of its six vice-presidents. “I am the only LPN of the six; we all come from different areas of union membership,” she explains. “My portfolio is the Edmonton area, so a significant amount of the membership in my area works in healthcare, plus I have regular contact with various other places, simply because of working for Alberta Health Services for 28 years.”

“We spend a lot of time rewarding people for being CEOs, but we don’t reward them for being a housekeeper, or for looking after your children,” says LPN Susan Slade (front, right). PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY AUPE

Slade says that pandemic mismanagement was there from the beginning in Alberta. “The first concerns we were hearing of course were around the personal protective equipment and the masks particularly. That has been ongoing ever since the very start of COVID.” Some masks caused facial irritation and rashes. “There was a massive concern about the PPE workers were being given, especially in our long-term care facilities.” Sometimes, at the very beginning of the pandemic, personal protective equipment was rationed, says Slade. “It wasn’t readily available.

“Then of course there’s the pandemic pay that was promised to the healthcare aides; that was said by the minister of health, but then he backtracked on that and said it wasn’t for everyone, it was only for certain groups of healthcare aides. So that created another fiasco.”

In November 2020, the Alberta Federation of Labour revealed that federal government documents showed the Kenney UCP government had refused to contribute to an “essential worker wage top-up program” (also known as “hero pay”) — provinces and territories were expected to contribute $1 billion to match the federal pledge of $3 billion. Because Alberta contributed only 3.5 per cent of what was expected, it could not access over $300 million designated to boost the pandemic wages of frontline workers.

“It was actually based on whether you worked in a private, for-profit care facility, and there were a whole bunch of parameters around it,” says Slade. “Then recently it’s been said that the provincial government didn’t apply for all of the federal funding that was available.”

Pandemic Pay for Everyone

Pandemic pay is not based on an individual’s job classification, and she argues that it shouldn’t be: “Everybody working the frontlines should be receiving pandemic pay, whether they are actually in healthcare or not.” It’s not only the high-profile doctors and nurses who have seen their lives broadsided by COVID-19, she adds, but workers much further down the pay scale: “It has increased workloads hugely, especially in healthcare, but of course we see that in other areas as well, so we’ve been continually talking, in the media especially, about the need to ensure that people are being paid properly. They are risking themselves every day that they go to work.”

Rather than recognizing the sacrifices made by essential workers and their families, the Kenney government chose to reward them with the news that they, and their colleagues in supporting roles, were dispensable. “The government did come out last fall, stating that they would be eliminating up to 1,000 jobs,” the LPN tells Our Times. “It’s a lot of frontline environmental services; they want to privatize it, take the laundry facilities out [of healthcare facilities].”

Citing the Ernst and Young report, Slade says it was commissioned to “find efficiencies within Alberta Health Services,” resulting in a familiar list of recommended “efficiencies”: “It actually came down to privatizing; selling off the rest of the public long-term care facilities, such as CapitalCare and Carewest, employers within Alberta, and privatizing those; privatizing the rest of the rural laundry facilities that aren’t privatized already; the environmental services; cutting numerous registered nursing jobs . . . The list goes on.”

But so does the pandemic, which, through fall and winter, transformed into an ominously escalating second wave in Alberta. On January 18, 2021, the province reported 117,767 total cases of confirmed COVID-19; 456 were reported for that date alone. While 105,208 people had recovered, 11,096 cases remained “active” and 740 of those patients were currently hospitalized. The total number of COVID-19 deaths in Alberta was 1,463, third among all provinces/territories, behind only Quebec and Ontario.

Registered nurse Pauline Worsfold is secretary-treasurer of the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions (CFNU) and a member of United Nurses of Alberta (UNA). PHOTOGRAPH: BLAIR GABLE

Registered nurse Pauline Worsfold works in the post-anesthetic recovery room at the University of Alberta Hospital in Edmonton. She’s also secretary-treasurer of the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions (CFNU) and a member of United Nurses of Alberta (UNA). “It’s kind of odd. Our work is dependent on the operating rooms. After you have surgery, you come first to the recovery room to recover from your anesthetic, and get any problems that you have sorted out before we send you to the post-op unit,” she says.

“During COVID, off and on, we’ve had to decrease surgeries to intentionally keep the hospital empty, to allow for COVID cases to be admitted.” The normal 17 operating rooms that can function concurrently have been reduced to just eight. The reduction in capacity means only emergency, trauma, and some cancer surgeries are scheduled, while less-urgent procedures have been postponed.

“We did the same thing in the spring [of 2020] when we expected the [COVID-19] numbers to be terrible, very high. When our numbers levelled off, we ramped up right away,” recalls Worsfold. “We were able to do lots of surgeries, to attempt to catch up from the ones that were postponed in the spring. I can foresee that we will be doing that again, as soon as our numbers are looking better.” (On the day of her interview, Alberta was second in the country by active cases per capita.)

Worsfold notes that some nurses were redeployed to virus-screening/testing, contact tracing, post-op units and intensive care units. Their adaptability and effort didn’t change the UCP government’s pursuit of efficiencies, however: “There was a rumour that was confirmed in the fall of last year, that they were planning on laying off 750 nurses,” she says. “Labour is always a low-hanging fruit, because we make up the largest portion of any budget, at the hospitals in particular. So the easiest way to balance the budget is to cut jobs. It’s not the right thing to do, because people need frontline workers there, to care for them, and not solely nurses, either.”

The heroism of auxiliary workers in hospitals and long-term care facilities was overshadowed by that of doctors and nurses, says Slade. The possibility of losing these essential healthcare team members to budget cuts, after COVID-19 numbers subsided, was simply offensive. “That is one of the reasons why there was a wildcat strike that happened on October 26,” she adds.

Outside the Royal Alexandra Hospital in Edmonton on October 26, 2020, the day of the wildcat strike. PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY AUPE

“That was the final straw. For months and months, you’re hearing about how you’re a ‘hero,’ but yeah . . . You’re going to be a ‘hero’ for however long the pandemic lasts and then we’re not going to need you, so you’re going to be gone and hitting the unemployment line.”

Monday morning, last October 26, these frontline workers instead joined the picket line at University of Alberta Hospital and Royal Alexandra Hospital in Edmonton; Foothills Medical Centre in Calgary; and other locations around the province, including Wetaskiwin, Leduc, Fort Saskatchewan, Cold Lake and St. Paul. Although frequently undervalued, these workers’ supporting roles in healthcare are undeniably important, notes Slade: “As an LPN who worked for many years within the system, we can’t do our jobs without the general support services: the housekeeping, the laundry, the clerical, the maintenance. That’s how a hospital runs and that’s how it ensures that it stays safe and clean, and that supplies are readily available.”

Privatization Damages Alberta's Healthcare

Outsourcing and privatization of these auxiliary positions would damage Alberta healthcare, because workers would seek better opportunities in other fields or places. “You don’t stay at a $15-an-hour job when you can go somewhere else to work for more money, so the continuity of care changes,” says Slade.

“We see that within long-term care facilities: People don’t stay, because they don’t make what they would at Alberta Health Services, which is the biggest employer in healthcare in this province. You need to have consistency to have well-run facilities, and people aren’t going to work for just minimum wage, nor should they.”

Budget cuts at direct personal cost to the “heroes” of the pandemic may have been planned before the crisis hit, but the inflexibility of Kenney and his health minister, Shandro, only highlights the injustice of holding the line now.

“To look after people, to look after facilities, and do all that . . . That is something that should be rewarded,” stresses Slade. “We spend a lot of time rewarding people for being CEOs and executives, but we certainly don’t reward them for being a housekeeper, or for looking after your children, or anything like that. It’s a very skewed system in our world right now.”

She adds that racialized workers and women still commonly do the heavy lifting in the lowest-paid essential jobs, indicating an unfair, if common, expectation that the work of care and cleaning is somehow natural for them, just like low wages. Highly educated immigrants unable to find employment in their field are often found working in hospital or long-term care facility kitchens, environmental services and laundries.

PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY AUPE

The AUPE vice-president says Alberta can do better for its “heroes”: “Even just as much as the pandemic pay would have gone a long way.” Limiting workers to one healthcare facility, to prevent spreading infection among vulnerable populations, has been termed the “one-site rule.” For some essential workers, it brought a fleeting sense of job security, but for others, it limited their ability to piece together an adequate income. Alberta nurses became eligible for paid sick days in late January 2021, in an agreement between the United Nurses of Alberta (UNA) and Alberta Health Services (AHS) that includes retroactive payment for employees who had to self-isolate from July 2, 2020. But paid sick leave remains an elusive goal for other frontline healthcare workers.

“There was no consultation with the unions so that we could actually figure something out,” Slade recalls, adding that their neighbouring province has implemented a better way to manage the pandemic: “BC had a great model: They brought everybody back into the public system. They brought all of their long-term care facilities, private, for-profit, back into their system to ensure that they had proper staffing levels. They ensured that people were being looked after. Alberta just makes an announcement, and then they change that announcement, or make a ministerial order with no thought to it.”

PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY PAULINE WORSFOLD

While RNs like Worsfold are not among the frontline workers threatened with post-COVID layoffs, she and many others stand in solidarity with the auxiliary workers and last fall’s wildcat strike. “It’s insulting, the way that we are just widgets, according to the government,” she quips. “How we can be moved around and replaced at any given time. And then to expect a high quality of healthcare to be delivered, at the same time? It’s absolute craziness.”

She has continued to work in her regular post-anesthesia room position. “For me, the piece that has changed is the number of cases that are either COVID-positive or presumed COVID-positive,” she explains. “We normally have patients come to us, in the recovery room; now, you go into the operating room and you gear up and wear all of your personal protective equipment.” She counts herself lucky to have adequate PPE.

Worsfold says she has never encountered another illness with an impact like COVID-19 in her 39 years of nursing. “I do see a flickering matchstick at the end of the tunnel, and that’s the vaccine rollout,” she adds. Worsfold has received her initial vaccination and made an appointment for her second dose.

But, like much in Alberta healthcare at the moment, even the vaccine-distribution plans were not communicated by the government in a coherent fashion.

Staff Frustration

“There’s a lot of staff frustration,” observes Sahra Kaahiye. “At the moment, they’re very confused as to the vaccine rollout. We have administration staff being vaccinated, for example, prior to emergency doctors and paramedics.” Add to this, technical glitches that have further hampered government communications with healthcare workers and, at the time of writing, pharmaceutical companies delaying vaccine shipments to Canada.

As a respiratory therapist frequently in close proximity to aerosol-generating medical procedures, she was the first person in Alberta to receive the vaccine. But Kaahiye doesn’t feel much like a hero. “Within my workplace, it’s mostly just status quo, in terms of what we’re doing, despite the pandemic,” she says. “Speaking for myself, and the people I’ve had conversations with, we always knew that there was going to be a risk with doing our jobs, similar to police officers.”

They didn’t count on the added danger, though, of a government that calls them “heroes” even as it continues to actively erode their working conditions and further jeopardize their health and safety.

“A lot of frontline healthcare workers that I’ve talked to are done after this pandemic,” says Kaahiye. “They’re stepping back and looking at alternatives, other jobs, other occupations, because they just feel so burnt out by what’s happening now.”

Melissa Keith is a former radio broadcaster and an award-winning freelance journalist. She lives in Lower Sackville, Nova Scotia.