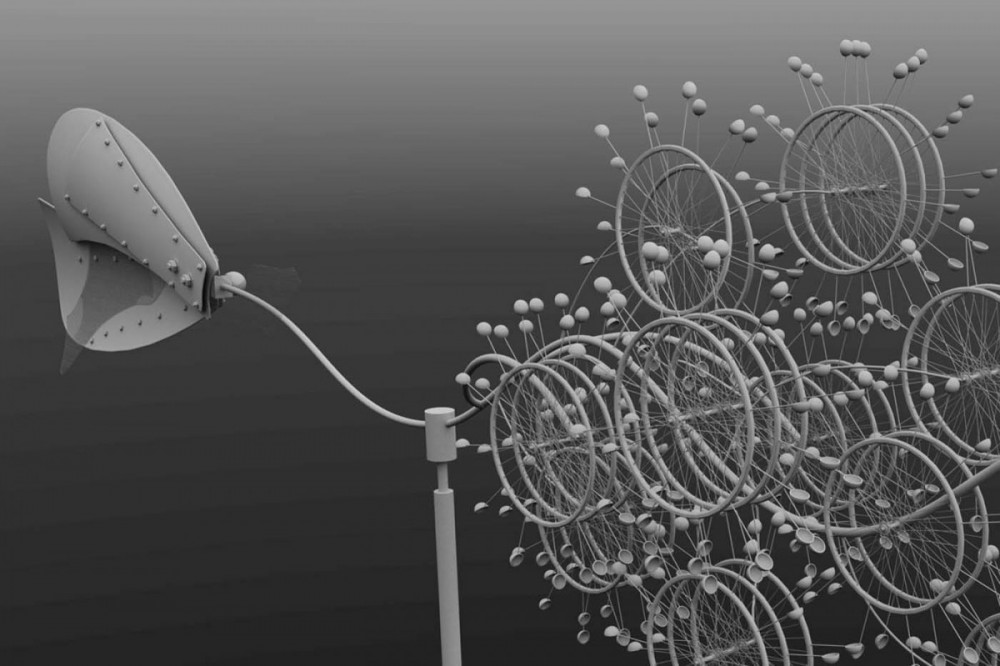

A seven-metre-high metal sculpture installed outdoors at the Vancouver Convention Centre will be sure to catch the eye of locals and tourists alike with its playful, wind-blown mobile of cups, spokes and wheels. But when viewers of the British Columbia Labour Heritage Centre (BCLHC) art project take a closer look, they will be in for a surprise.

WIND WHEEL MOBILE (DETAIL): COURTESY DOUG TAYLOR

“Wind Wheel Mobile” by Vancouver artist Doug Taylor has a very serious message: the art piece, scheduled to be unveiled this spring, is a memorial to workers who have died from asbestos-related illnesses. Once considered the “magic mineral,” asbestos is still the number one killer of BC workers, with 47 deaths in 2018 alone. Across North America, the mineral’s deadly fibres are responsible for 40 per cent of workplace deaths.

“We decided against a memorial that was traditional and sombre,” says Joey Hartman, Chair of the BCLHC and past president of the Vancouver & District Labour Council. “Doug’s work is whimsical, light and kinetic. It will get people to pause and say ‘what is this?’”

The sculpture’s location alongside a working port dotted with cargo ships that once carried asbestos is significant too. “The memorial recognizes and acknowledges the people who have died,” Hartman says. “It’s a symbolic reminder that workers are put at risk in so many ways.”

Joey Hartman (right, at a CoDev meeting) is Chair of the BC Labour Heritage Centre. PHOTOGRAPH: JOSHUA BERSON

Asbestos has been removed from most industrial sites due to the advocacy of trade unions and other groups, but the sculpture serves as a reminder that the campaign is far from over.

“Asbestos is in thousands of buildings people live and work in today,” Hartman says, “including schools, hospitals and offices constructed before 1990. Every public building has had asbestos in it. If something punctures a wall, it can trigger a fatal disease.”

House renovations and demolitions are also hazardous. When asbestos removal is undertaken, work surfaces must be protected with plastic sheets or tarps to help control the spread of the material, decontamination procedures followed, and the substance safely removed and disposed of.

The latest addition to the many BCLHC labour history plaques erected outside the convention centre, the memorial is located at the foot of the “Line of Work” installation that profiles workers killed or injured on the job.

“It captures the imagination,” Hartman says about the sculpture. “People can stop to read the poem ‘Magic and Lethal’ by John Gray.”

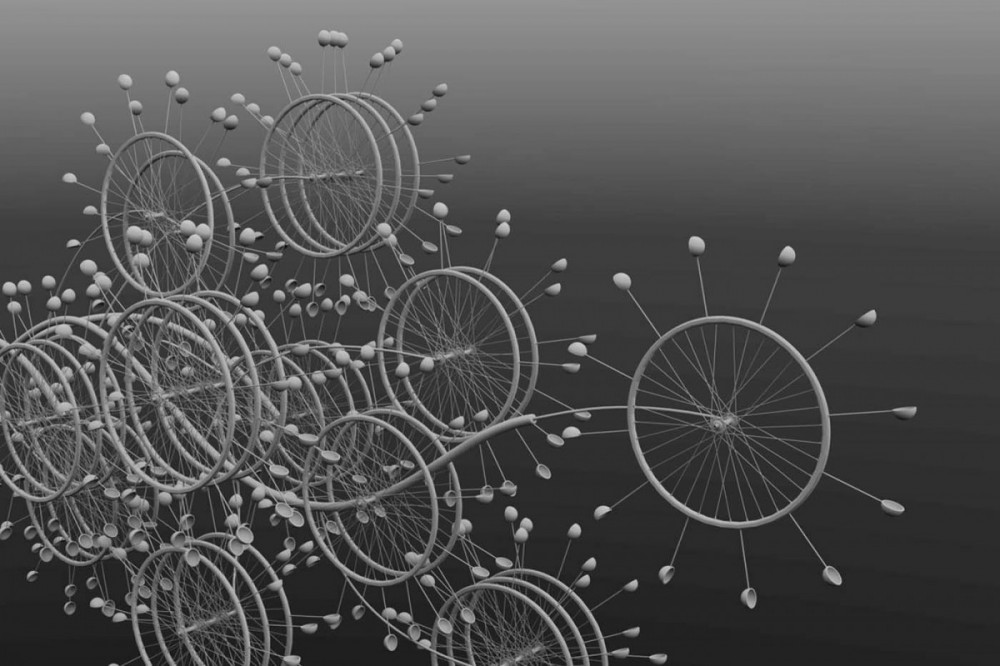

WIND WHEEL MOBILE (DETAIL): COURTESY DOUG TAYLOR

The spokes and wheels of the sculpture resemble asbestos fibres and molecules. The entire metal work, driven by the wind, evokes a visual connection to the lungs and bronchial airways of the human body. This artistic interpretation is clear to Lee Loftus, a BCLHC board member and former president of the BC Insulators Union Local 188. A longtime health-and-safety advocate, Loftus was exposed to asbestos while working in Northern BC and at the Vancouver shipyard of the Burrard Dry Dock Company. When he saw a model of Taylor’s sculpture, he knew it was the right choice as a memorial.

“I saw the lungs (on the sculpture) and thought about the fibres airborne in the sun, flooding the shipyard,” Loftus said. “His art hit me. He understood. Those fibres chase you and attack.

“His art hit me,” says Lee Loftus of Doug Taylor’s sculpture. “He understood. Those fibres chase you and attack.” PHOTOGRAPH: JOSHUA BERSON

“In 1974, I was a young worker apprenticing in an oil refinery in Northern BC,” Loftus says. “I wore a dust mask while removing asbestos and storing it. Then I went on to work in the shipyard up to the 1980s.”

Dust masks became mandatory for workers only in 1985, he says, and the use of superior protective equipment wasn’t enforced until the 1990s. By the year 2000, Loftus began experiencing the physical impact of exposure to asbestos fibres. He went for medical tests.

“The lower lobes of my lungs are scarred,” he says. “Both linings are impacted, and I have 20 per cent loss in the function of my lungs. I am now 65.”

Loftus has trouble breathing after climbing three flights of stairs. He suffers from asbestosis, a non-cancerous disease of the lungs and respiratory tract brought on by asbestos exposure. Lung tissue thickens and becomes stiff as asbestos fibres travel through the lungs and permanently scar them.

Loftus participates in health studies and is involved in helping others who are dealing with the same medical condition. He has also seen many fellow workers coping with mesothelioma, a cancer that develops usually in the lungs and abdomen. It is caused only by exposure to asbestos, he says. It is incurable and undetectable until stage three. After that, someone may live for only a few months more. It is a very painful way to die.

“My son is in the insulation industry. He is in a unionized construction sector and has PPE. But there’s an underground economy here doing renovations, and asbestos is not managed properly.”

Loftus says asbestos was used in the late 1930s across North America and, by the 1950s, was widespread. The townspeople of Cassiar in Northern BC once mined asbestos. “Asbestos was hanging like snow in the trees,” he says.

“There was about 40 years of high productivity, and then in 1985, asbestos was out of production.”

Cassiar wharf facilities. PHOTOGRAPH: JOSHUA BERSON

He mentions the Cassiar Asbestos wharf facilities, where asbestos was loaded onto ships and exported, in North Vancouver, across Burrard Inlet and visible from the memorial sculpture. Currently there are two great piles of yellow sulphur on the shoreline but, Loftus points out, asbestos was once stored there.

“The location of the sculpture speaks volumes on how important the impact [of asbestos] on BC workers is.”

Despite knowledge of the dangers, the import and export of asbestos in Canada was banned only in 2018. Loftus says government regulations are still a work in progress. Residences and commercial buildings in particular remain a problem, and he believes the BC government should introduce mandatory licensing for all asbestos-removal and testing firms in the province.

“Asbestos is still being dumped in parks and laneways,” Loftus says, “and people are being exposed. Every year the provincial government doesn’t enact regulations, more people die. There’s an urgency.”

Al Johnson is head of Prevention Services for WorkSafeBC, the provincial agency providing a generous financial donation to the BCHLC for the sculpture project.

“There was gross exposure decades ago,” Johnson says about asbestos, echoing Loftus’ words. “Typically, it is not happening in heavy industries today. It’s still happening primarily in residential and commercial buildings with demolition and renovations, where there is pre-1990 asbestos in buildings. It’s still killing workers.”

WorkSafe campaigns to raise awareness about the hazards of asbestos, he says, and promotes the hiring of reputable contractors and the protection of workers and homeowners.

“You can be breathing fibres today,” Johnson says, “and don’t know you have symptoms. You don’t react. The fibres go deep in the lungs. It’s 10 to 30 years after, when the disease takes hold.”

White Asbestos Was Used as Snow on Movie Sets

Johnson says in the 1940s asbestos was considered miraculous, safe and harmless. “White asbestos was used as snow on movie sets,” he says. It was also used for fireproofing between floors. Workers sprayed asbestos on walls of buildings and didn’t wear masks. “It didn’t burn or break down,” he says of the substance. “It was clean. It had a thousand uses.”

All that changed by the 1960s. “It was seen as bad. It kills.

“The memorial is an opportunity to reflect on the lives lost and to message on asbestos and bring further attention,” Johnson believes. “If we eliminate exposure to asbestos, then we will eliminate the disease."

“I love to build weathervanes, mobiles and kinetic sculptures that reflect the spirit and storyline of a site,” says Doug Taylor in his artist statement. PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY DOUG TAYLOR

Doug Taylor says it took him 30 years of trial and error before he began producing public sculptures that did not require maintenance. He also says it was synchronistic that the whimsical, folk-art inspired elements of his sculpture matched the vision of BCLHC members.

“Lee (Loftus) is pivotal in the sense that he recognized the many features of the kinetic sculpture that relate to the asbestos subject,” Taylor says. “You are breathing in air full of particles you are not aware of. Normally they are invisible. Floating particulars of asbestos are much like a floating sunbeam. Lee was able to identify different features of the sculpture.”

Viewers arriving after dark to take in the metal work will be in for another surprise, according to Taylor. “The 32 wheels on the sculpture light up like a candelabra at night,” he promises.

The Wind Wheel Mobile is expected to be installed in the coming months, with the BCLHC's launch this spring including a short video on asbestos and the memorial. For more information, visit: labourheritagecentre.ca/asbestos.

Janet Nicol is a freelance writer. Her most recent article for Our Times is on the BCLHC Covid Chronicles project. She blogs at janetnicol.wordpress.com.