Northern Ontario, my home region, has been put through the wringer. It has hemorrhaged jobs and people since the 1970s. As a result, the region is littered with former paper mill towns, sawmill towns, railway towns, and now university towns. An entire region has become politically disposable. It makes me more angry than sad.

The statistics tell part of the story. The population of Northern Ontario declined from 822,445 in 1986 to just 775,180 in 2011. Its proportion of the province’s population has likewise fallen from 6.2 per cent to just 4.1 per cent. The exodus of young people has left behind an aging population.

Only Sudbury, the region’s largest city, with 165,000 people, bucks the trend to some extent. While mining remains important to the city, Sudbury has emerged as an important regional centre for health care and education. Laurentian University has contributed mightily to this one regional bright spot. This university is unique in so far as it has a tricultural and bilingual mandate.

Today, that mandate is in tatters.

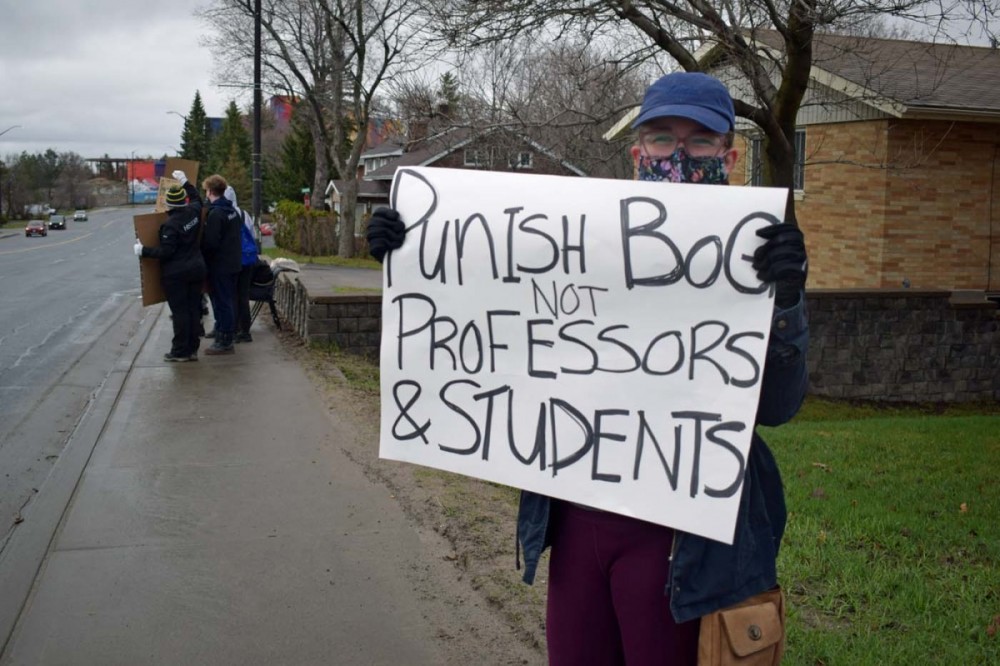

PHOTOGRAPH: LOU HAYDEN

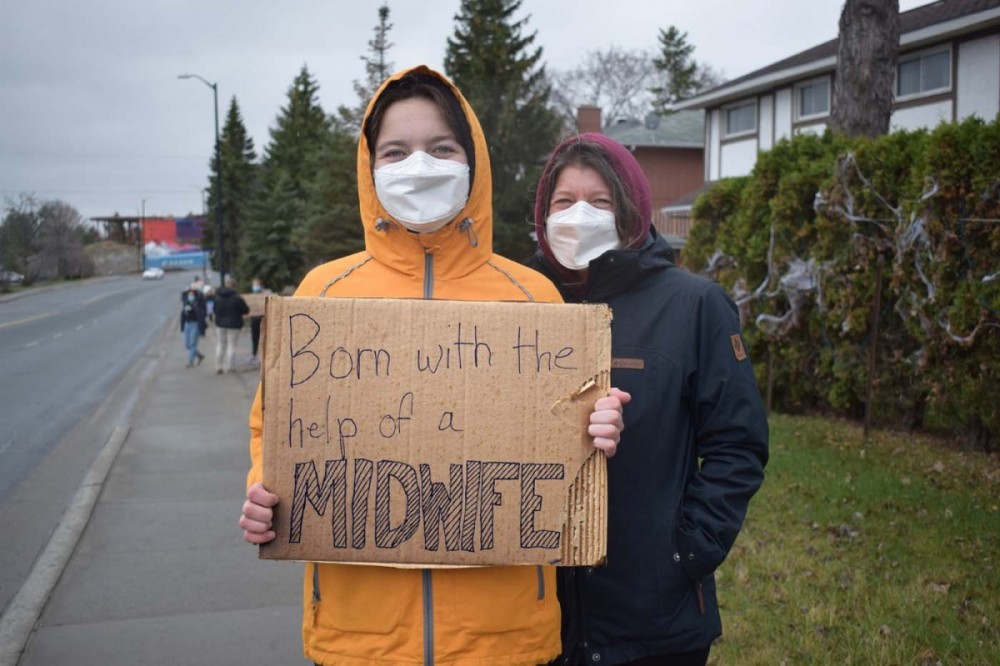

Laurentian first terminated its relationship to its federated colleges — which are now unable to grant degrees, effectively killing them — and then closed 69 undergraduate and graduate programs. Many of the programs were in the humanities and a disproportionate number were French-language. The school is also ending its bilingual midwifery program, the only one of its kind in Canada, as well as its Indigenous Studies program, one of the first in the country.

The loss of Laurentian’s two graduate history programs will be felt for years to come. What little is known about Northern Ontario’s largely-overlooked history is thanks to these programs. The assault on Laurentian is yet another act of regional erasure.

Hundreds of “permanent” staff are being terminated without severance pay.

PHOTOGRAPH: LOU HAYDEN

The dismantling of Laurentian University under the federal Companies Creditor Arrangements Act (CCAA) is unprecedented. In fact, until the late 1990s, the law only applied to the private sector. We can thank the Liberals for this.

The CCAA gives companies experiencing financial difficulty the opportunity to break collective agreements and to radically restructure in order to return to profitability. Too often, this has meant mass layoffs and lost pensions. Now this blunt — and deeply unfair — instrument is being wielded against the public sector. What is happening to Laurentian University strikes to the heart of our public system. A university is not a for-profit corporation. Nor is a hospital.

Make no mistake, Laurentian is only in creditor’s protection because Ontario’s Tory government refused to step in.

The unprecedented nature of what is happening to Laurentian University is a big reason why there is so much anger and disbelief. The public sector is the last vestige of the old and honourable union idea that if you work hard and put in your time — you can retire in dignity. It is an idea that has been under assault in the private sector since the 1970s.

Post-war gains continue to be rolled back.

“Sage-Femmes” (sign on left) is French for midwives (“midwives are necessary”). PHOTOGRAPH: LOU HAYDEN

The 1950s and 1960s were a period of economic growth and unionized prosperity across the industrialized world. The French call these years the “trentes glorieuses;” the British call them the “long boom;” and American historian Jefferson Cowie has referred to this period as the “Great Exception” in a longer history of savage capitalism.

Northern Ontario’s experience was no different. A high level of unionization resulted in collectively bargained social mobility for many blue-collar families who could aspire to send their children to college or university. I was one of these working-class children. The establishment of new regional universities in Thunder Bay and Sudbury greatly facilitated our social advancement. Other universities followed in North Bay and Sault Ste Marie.

The end of the postwar boom played a big part in Laurentian University’s financial troubles. Deindustrialization has led to demographic decline, reducing the geographic pool of potential students, and placing new barriers to social mobility. Northern Ontario residents are older and poorer than they used to be.

Meanwhile, an ideologically-driven Ontario government sharply reduced its financial contribution to the university sector. This had an out-sized impact on working-class universities that don’t have ties to the rich donor class. In the name of institutional survival, three Northern Ontario universities opened new satellite campuses in central Ontario. It was a failed experiment, with two quickly closing (including Laurentian’s campus in Barrie), further sapping their resources. International student recruitment was the next big thing — but COVID-19 ended that.

The unfairness of the unfolding situation is there to see.

PHOTOGRAPH: LOU HAYDEN

Another reason why Laurentian University has received so much public attention in recent weeks is its importance to Franco-Ontarians. The dismantling of a bilingual university has served to politicize the story nationally in a way that would have been (sadly) almost impossible otherwise. Laurentian is headline news in Quebec. I can’t imagine the federal parliament having an emergency debate otherwise. But is Toronto listening?

I can assure you that the region did not get this kind of attention when the forestry crisis devastated dozens of working-class communities. Few outside the region ever heard of Fort Frances, Red Rock, Marathon, Smooth Rock Falls, Iroquois Falls, and Sturgeon Falls. These towns all lost their paper mills. The response? Only silence.

Otherwise, much of the news coverage of the Laurentian story is familiar to me. Since the 1970s there has been almost a genre of news reporting on the “last shift,” one that strikes a melancholy tone but ends in a shrug. The media needs to ask the hard questions.

Laurentian’s announcement was made right in the middle of final exams for students, adding insult to injury. One would have been hard-pressed to pick a worse time. The university’s upper administration has no business remaining in their jobs. But that is so often the way, isn’t it?

Deindustrialization and Being Left Behind

In my mind, the dismantling of Laurentian University is part of the wider process of deindustrialization that continues to empty the region. Those left behind are older, poorer, and less well-educated. In this, Northern Ontario is not alone.

As a share of total employment, Canadian manufacturing fell from 22 per cent in 1973 to 15.3 per cent in 2000 and just 10.3 per cent in 2010. The body count was staggering. Seventy-five per cent of all the mills and factories operating in Canada in 1961 were closed by 1991. Another study found that one million manufacturing jobs present in 1973 were gone by 1996, or two-thirds of the total. Other jobs were being created, of course, but usually not ones that paid the same decent wages or that were located nearby. Increasingly, Canadian mills and factories have short working lives — a fact that has profound consequences for remote regions and working-class communities.

Take Action Now

Universities like Laurentian are needed now more than ever, as are trade unions. The working-class dream of collectively-bargained social mobility is under threat, as are working-class universities. We need to act. Visit the Ontario Confederation of Faculty Unions (OCUFA) for updates and actions. As well, see the five things the Canadian Association of University Teachers is encoureaging us to do:

- Reach out to your Member of Parliament to call for federal action.

- Put pressure on the provincial government by signing the Laurentian University Faculty Association's (LUFA) letter.

- Show solidarity with a letter or a motion.

- Amplify the need for action on social media.

- Learn more about the issues.

Steven High is a Professor of History at Concordia University and is the author One Job Town: Work, Memory and Betrayal in Northern Ontario. He is originally from Thunder Bay.