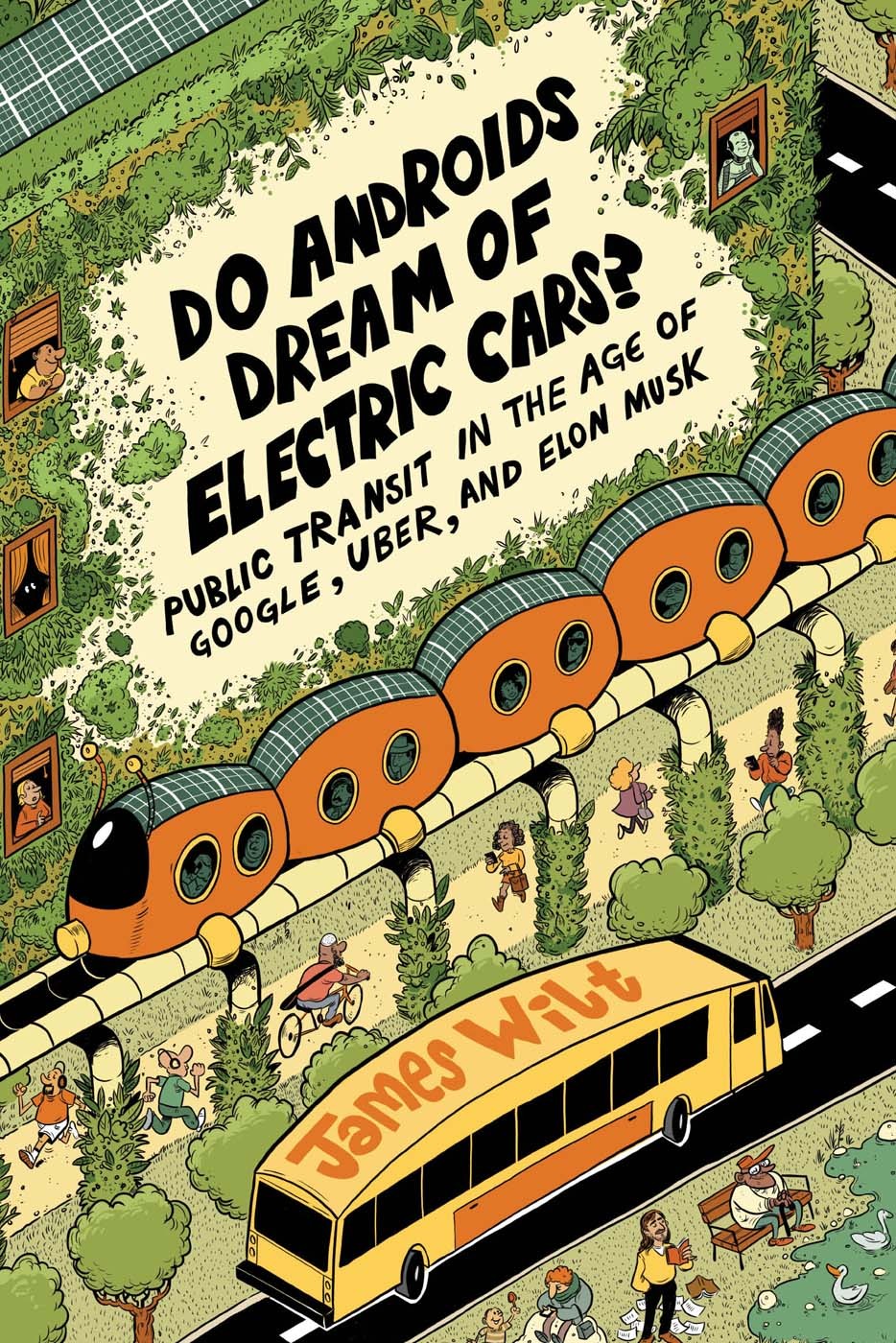

DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF ELECTRIC CARS? Public Transit in the Age of Google, Uber and Elon Musk

Between the Lines, 293 PAGES, $27.95

ISBN 9781771134484

Famous science fiction writer William Gibson once quipped that “the future is already here — it’s just not evenly distributed.” It’s a sentiment that aptly describes technology and transit. The rich in Canada can buy top-of-the-line electric cars from Tesla. They can buy digital passes to the privatized 407 highway and bypass most of Toronto’s traffic. Many hope to soon be able to buy fully autonomous vehicles and leave all the driving to computers.

It seems fitting then that the title of James Wilt’s book is a play on the title of a sci-fi novel by Philip K. Dick, who was a contemporary of Gibson. Do Androids Dream of Electric Cars? presents two visions of the future of transportation: one designed by ultra-rich libertarians like Tesla CEO Elon Musk and centred almost entirely on the personal vehicle; the other, designed with the public good in mind and centred on fast, efficient, expanded and accessible transit — a vision that gives everyone the chance to thrive.

Fortunately, Wilt does more than imagine possible futures. Through impressive research and clear writing, he not only paints the picture of the world we want, but provides a road map for how to get there.

To understand where we need to go, Wilt first explores how we got here. Decades of austerity have starved public transit systems of funding, led to the privatization of routes and entire services, and neglected the needs of riders. Today, most transit systems across North America are slow and outdated. They charge high fares, while forcing riders to transfer numerous times during each trip, just to get close to where they want to go. Worse, many neighbourhoods and suburbs have no service at all.

Given the failings of public transit, it’s no wonder that the tech entrepreneurs have stepped in to fill the gap. Enter the “three revolutions” in transportation: electric vehicles, ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft, and autonomous vehicles. These revolutions are hailed as solutions to not just inadequate and inaccessible public transit, but also to traffic congestion, inequality, and climate change.

As Wilt shows, though, no amount of "ingenuity" springing from the minds of eccentric billionaires will save us. The “three revolutions” are really just the next frontier of neoliberalism. The tech companies behind them are trying to disrupt and ultimately replace public transit. In some places, that future is already here.

Uber in Innisfil

Just north of Toronto, the town of Innisfil subsidizes Uber trips for residents instead of creating new bus routes. The town has reached an agreement with the tech company to offer passengers a flat $3 to $5 fare within the core area. Outside that area, they receive $5 off their fare. The program has become so popular that Innisfil now pays Uber over a million dollars per year — far more than several new bus routes would cost. To rein in the runaway cost, the town has limited use to 30 rides per month.

Even electric cars are not the panacea to climate change they appear to be. Manufacturing electric vehicles requires mining raw materials, often in conflict zones with few to no labour laws. Wilt notes that “replacing all two billion cars worldwide would require a 70 per cent increase in the production of neodymium and dysprosium, a doubling of copper output, and over a tripling in cobalt mining.” The federal government recently promised up to $500 million in funding to subsidize Ford Motor Co. to bring electric vehicle production to its Oakville assembly complex. It’s a move that will continue that trend, while doing little to meet our climate targets.

Manufacturing concerns aside, electric cars are wildly more inefficient than electric buses. Cars are often used for only one or two hours a day. To produce, not to mention constantly charge, vehicles that sit unused most of the time is an incredible waste of energy, especially when you consider that buses run up to 18 hours per day. As Wilt lays out, “It takes 100 personal electric vehicles to provide the same ‘environmental relief’ as can be gained by a single 60-foot electric bus.”

Reducing Our Reliance on Personal Vehicles

Put simply, there is no way to reduce carbon emissions without reducing our reliance on personal vehicles. Rather than guilt consumers into choosing public transit, Wilt lays the responsibility squarely with transit agencies, politicians, and advocates. Public transit must become more attractive than driving. It must be cheaper (or free!), faster, more accessible, and easier to use than private vehicles or ride-sharing apps. It will require major investments, but will be cheaper and provide far better and more expansive coverage than tech companies ever could.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Cars? could not be better-timed. The outbreak of COVID-19 and the measures taken to combat the pandemic have put public transit systems on life support. Ridership is now at historic lows. Transit agencies in major cities have cut hundreds of millions of dollars in funding, reduced service by up to 50 per cent, and laid off thousands of workers.

In the context of the current crisis, Wilt lays out the fight over the future of transportation. Will it be publicly or privately owned? Will decisions be made democratically by local residents, or by shareholders and a handful of CEOs in San Francisco?

The choice, after all, is over how evenly distributed the future will be. Wilt’s vision is “one of shared power: among workers, tenants, bus riders, migrants, people with disabilities, youth, and seniors. [Where] a future of ecological, reliable, free, and accessible public transportation awaits us.”

James Wilt’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Cars? is perfect for anyone who wants to understand how transit systems work, how they’re currently failing us, and which risks we may encounter in trying to solve those failures solely through the three revolutions. It also provides ample fuel, or battery power, for advocacy.

James Hutt is a labour organizer, writer, and climate activist on unceded Algonquin Anishinaabe territory (Ottawa).