Working people in Canada rely on a robust set of employment laws and regulations designed for their protection. Anti-discrimination laws, minimum-wage standards and sexual-harassment policies help safeguard us from oppressive structures in our society. The Canadian labour movement is largely responsible for these successes and continues to represent over 3.3 million workers today. Though public support for organized labour has declined, inequitable conditions exacerbated by the pandemic have revived many workers’ interest in unions. While critics claim that unions promote mediocracy, inflate compensations, protect lazy workers, and provide undeserved job security, there is another narrative taking hold: As billionaires’ wealth skyrockets and working people find themselves struggling with even greater precarity, unions have much to offer.

Who or what are we leaving out?

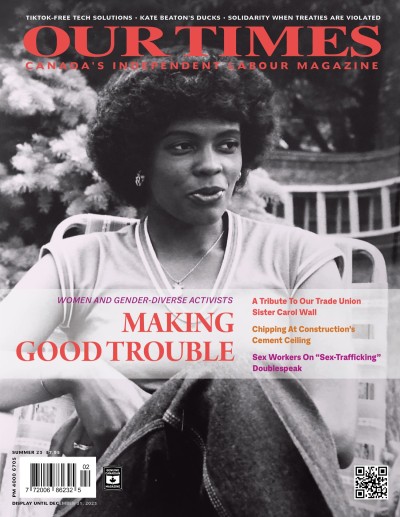

Forces such as settler colonialism and neoliberalism subjugate people on a physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual level daily. Discrimination in its many forms threatens our country’s rich social fabric, including the workplaces of union members and the communities in which they live. Using race, religion, gender, or ancestry to divide people undermines human rights everywhere and serves only to weaken us all. Personal beliefs, cultural norms, structural institutions, and spiritual views all converge to produce unequal power relations between individuals.

The politics of recognition is a concept that helps explain how “misrecognizing” is a form of oppression that harms and distorts people’s lives. Misrecognizing someone is the act of deliberately failing to acknowledge a person’s positionality, or pretending to do so. Our identities are often largely shaped by acceptance, or the lack of it, and so trade unionists in the labour movement must look at how they conceptualize inclusive workplaces. Who or what are we leaving out?

We are leaving out spirituality and religion. Spirituality should be understood the same way as other markers of difference like gender, race, ability, and sexual orientation. By examining the religious and spiritual proclivities of Canadians we can gain further insight into how this facet of our lives informs our experiences.

Most Canadians believe in a higher power

In 2017, an Angus Reid study found that most Canadians characterize themselves as religious and believe in the existence of a higher power. The study also discovered that we enjoy maintaining a high degree of spiritual life. New immigrants, many of whom are racialized and belong to religions other than Christianity, were also linked to the increased growth in faith-based communities. Women had a higher propensity for spirituality than did their male counterparts and placed considerable importance on it. Ultimately, the data suggest that religious and spiritual identities are static, reflect various worldviews and are both internally and externally diverse. They are a critical component of who we are. So why does secularism dominate our public sphere then? Particularly in the workplace?

The shift to secularism had noble beginnings. It was designed to offset dominant Judeo-Christian ideologies pervasive in our Canadian establishment until the 1960s. Unfortunately, as the role of religion in our state apparatus vanished, so did the platform used to openly express our spiritual identities. One’s spiritual fulfillment was relegated to the private domain, and it became a classic case of throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Secularism was a worthy cause

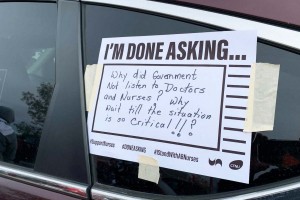

While secularism in the name of equity is a worthy cause, it has created other inequitable conditions we cannot afford to ignore. In 2019, Quebec successfully passed Bill 21 and banned public servants in a position of authority from wearing religious symbols or covering their faces while on the job. Overnight, hijabs, turbans, kippahs, and crucifixes were outlawed. Bigotry was legally sanctioned.

For some, Bill 21 was a solution to the threat of multiculturalism and erasure of what they saw as a distinct, French-speaking cultural element of the province. For others it was an infringement of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. For much of the labour movement it was a failure to respond to a watershed moment in our country’s history.

Let’s look at frontline healthcare workers for an example. While women account for 83 per cent of this workforce, women of colour and new immigrants are over-represented across all its occupations. Many of them are part of the same demographic cited earlier, from the Angus Reid study, who value their religious identities. These workers are profoundly giving people who utilize their spirituality as a mechanism to inform their work and the relationships around them. So, what is the solution for individuals made to suffer a spiritual crisis because they cannot hold their dying resident’s hand and pray with them on their deathbed? Especially in a time of unprecedented death as a result of the current global pandemic.

A true celebration of difference

The answer can be found in religious literacy. As a national lens, it offers us a way to look at how to deconstruct paradigms designed to divide us, and a path forward. Through awareness and the true celebration of difference, we are better positioned to add more soldiers to our army of social justice warriors. By creating space in our general-membership meetings, stewards’ trainings, executive-board meetings, conventions, bargaining tables, and labour-management agendas we can prioritize the conversation. We must strengthen our commitment to the tenets of equality, respect, and justice for all by linking arms with the 3.3 million spiritually diverse members that we serve. We must redefine our ethos and focus on promoting spiritually inclusive workplaces. Who knows, we might even see public sentiment sway back in our favour.

Riley Richman has over a decade of experience working in the labour movement in various capacities including organizing, member leadership development, social justice and equity building, and strategic campaigns.