In 1963 when Gale Tyler started teaching elementary school in Coquitlam, she wasn't a feminist. "I had no understanding of sex discrimination whatsoever," she recalled.

But soon enough Gale's teaching career and ultimately her whole life would be transformed by the feminist revolution sweeping schools and society in those heady decades beginning in the swinging Sixties.

Similarly, when Linda Shuto started teaching in Burnaby in 1969 she never imagined she'd become a leading champion of women's rights within the BC Teachers' Federation.

It started with a simple decision to ignore the rule that said women teachers had to wear skirts. Instead, Linda chose to dress for the demands of her job, both in the classroom and in the school gym.

"One day I had to change my clothes four times and I thought, 'This is ridiculous. I'm going to wear pants to school.' So I did. Well, it almost caused a revolution! The principal called a staff meeting and said we had to vote on whether it would be allowed.

Only one guy stuck up for me, but all the rest of the staff voted against me. I felt like I was having a nervous breakdown just for standing up."

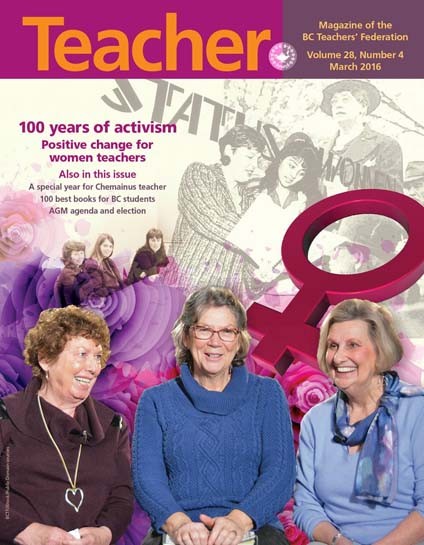

WOMEN OF WIT

Gale and Linda soon met through a fledgling group called Women in Teaching or WIT, as it was fondly known by its members. "The culture of the Federation at that time was incredibly male-dominated," Gale said. "So of course the men called us the TITs or TWATs or SHITs or whatever they could to make us look silly."

But the women of WIT would soon prove to be smarter and more strategic than the "male chauvinists" who tried to block the fundamental changes they were advocating for within their union and their schools.

And the winds of change were blowing in their direction.

At the federal level, the 1970 Report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women provided a framework for their goals and a tool to recruit more teachers to their cause.

Provincially, the NDP Education Minister of the day, Eileen Dailly, established an Advisory Committee on Sex Discrimination and asked UBC education professor Jane Gaskell to write a women's studies curriculum for secondary students.

Gaskell, who later went on to become dean of the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at University of Toronto, recruited Jane Turner, one of her students, to co-write the curriculum.

Through that work Jane met Gale and Linda, and lifelong friendships were forged. "It was a heady time, for sure," Jane recalled.

Meanwhile WIT was successful in getting a Task Force on the Status of Women established within the Federation.

But in contrast to the grassroots-up feminist processes of WIT, the BCTF president of the day took a top-down approach and simply appointed all of the members, including several men, two administrators, and Linda as the chair.

"The task force was a disaster," she recalled. "Everything I suggested, they'd say, 'Oh no, you can't do that.' I was beside myself!" The task force's final report was so bad that Linda presented a dissenting "minority report" to the BCTF Executive Committee.

"Amazingly, the Executive Committee then dismissed the [first] task force with thanks and appointed a new one with me, Gale, Julia Golden and Dorothy Glass. Then we could really go to town!"

They tackled sexism in schools with a variety of strategies. They conducted a textbook study, analyzing how teaching materials reinforced traditional roles for males and females — right down to the little animals in children's stories.

"It was a huge awakening to go back to our textbooks and to realize how gender stereotyped they were," said Gale.

ROBERTA'S RULES OF ORDER

They aimed to open doors at school for both boys and girls, lobbying for co-educational home economics and industrial education classes.

They examined counselling practices and the way traditional gender role assumptions limited girls' goals and dreams for the future.

"Girls were told they could go into teaching, nursing or secretarial jobs if they wanted to work for a while before becoming full-time moms. There was no impetus for counsellors to be aware of those biases," Linda said.

They challenged rules that made it mandatory for women to quit teaching when they got pregnant. They demanded their locals and the Federation provide child care at meetings, creating the first generation of "BCTF babies" who grew up together at AGMs.

Throughout it all, they worked "the second shift," juggling the many demands of teaching, marriage, motherhood, and activism.

"Before going to conferences, I'd make all of my husband's meals ahead of time and freeze them — but not tell my feminist friends I'd done that, since it was so pathetic," Gale laughed.

WIT's next success was persuading the Federation to establish a Status of Women committee (chaired by Gale), supported by one staff person (Linda), informed by a network of contacts in every local, and adequately funded to meet seven times a year for training and mutual support.

They published a monthly journal and hosted sold-out conferences that attracted up to 500 teachers. They offered public speaking, assertiveness training, and "Roberta's Rules of Order" workshops.

STANDING STRONG THROUGH THE BACKLASH

"We knew we had to win people over, get them to discard the myths that we were bra-burners and man-haters," Linda said. Her message? "If we're ever going to have a world of equal opportunities, teachers have to take this on."

But inevitably their success provoked a powerful backlash.

All of the Status of Women activists were mocked, shouted at, groped, and subjected to endless sexist jokes. "We used to say, 'If you're not getting any flak, you're not pushing hard enough.' We didn't shy away from anything," Linda added.

She recalled being invited to give a lunchtime address at a local professional development day. Some of the male teachers loudly made it known that they were heading to a local strip club for lunch.

During her presentation, another male teacher paraded behind her carrying a placard that read: "Eve was God's first mistake."

Linda was shocked by his behaviour, but chose to just ignore him and carry on. However, other teachers were so outraged that they went to the local executive and demanded that the next professional development day be entirely devoted to women's issues.

In an even more outrageous expression of the anti-feminist backlash, Gale was physically attacked by a principal in the elevator of the Hyatt Regency Hotel during a BCTF AGM.

"I later realized it wasn't me he was attacking. It was the change that I represented."

FROM WIT TO WIN

For that change to be durable, the women knew they had to consolidate their wins in collective agreements. Thus was born a new group called WIN, Women in Negotiations.

"In those days we had local bargaining, and that really helped women to be integrated into the union," Linda said. As a member and later chair of the Status of Women committee from 1977 to 1981, Jane focused on systemic change and bringing feminist processes and women's goals into contract negotiations.

At the bargaining table, WIN fought for maternity leave, part-time work, equal pay, fair pensions, and freedom from sexual harassment on the job.

In the classroom they fought for curricular changes to bring equal opportunities for both girls and boys.

And in the streets, they fought for women's right to choose, access to safe birth control, freedom from domestic violence, and more.

"You didn't have to hide anymore if you'd experienced sexual assault, rape, harassment in the workplace, or violence at home. We opened issues that had been hidden and not lanced, if you will," Jane said. "We experienced the personal liberation of people taking their own power back."

CONNECTING INTERNATIONALLY

In 1998 the Status of Women program marked its 25th anniversary, even as it ceased to exist within the Federation.

In a highly contested and razor-close vote, AGM delegates decided to adopt an integrated Social Justice program rather than have discrete programs. Gale made an impassioned speech urging delegates to defeat the motion. "After 25 years, we must not allow our voices to be silenced."

And indeed, those passionate voices of women in teaching have been far from silent, despite the demise of the discrete Status of Women program.

Their program has had an impact far beyond BC. It became a model for other unions across Canada and in many other parts of the world.

Through the Federation's International Solidarity program, women in Latin America are being trained and encouraged to take on leadership roles within their unions. In Honduras and El Salvador, women's networks supported by the BCTF have implemented non-sexist pedagogy programs to combat the strong culture of "machismo" in their schools and society.

Today, women's voices still ring loud and clear within the BCTF. And the Status of Women Action Group continues to carry on the tradition of sisters like Gale, Linda, and Jane by raising issues and making positive change for women teachers.

This article was first published in Teacher (Vol. 28, No.4), the BC Teachers' Federation's magazine. It is republished here with permission.

A lot of great articles and commentaries cross our desks from the internal union press in Canada, and we've long thought they deserve a wider, public audience, as a way to build the movement for workers' rights and social justice. With that in mind, we present Our Times' new online series, "Best of the Union Press." This first instalment is from the BC Teachers' Federation (BCTF). If you have a suggestion for what we might post next, please email us, attention: Best of the Union Press.

— Our Times

Nancy Knickerbocker serves as Director of Communications and Campaigns for the BC Teachers’ Federation (BCTF).