Next time you’re dazzled by the animation or special effects in a film or video game, consider the artists behind the scenes. In Vancouver — Canada’s largest animation hub — many love their work but not their working conditions.

“They are creatively strip mining us,” says Vanessa Kelly.

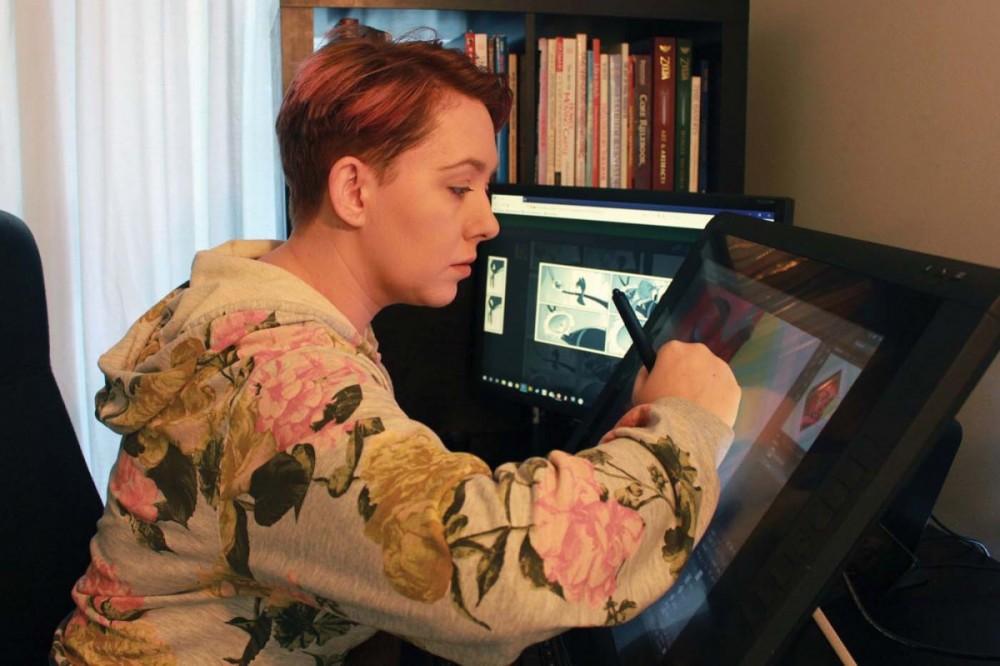

The former animator says unfair working conditions have created a “powder keg” inside dozens of the city’s studios, and she knows from personal experience. After getting a BFA in Visual Arts from Simon Fraser University and an Associate’s degree in Commercial Animation from Capilano University in North Vancouver, Vanessa worked as a storyboard artist for five years. Her studio tasks entailed working from a script to draw characters, often multiple times and in collaboration with the director.

Now she advocates for animators as a member of the Art Babbitt Appreciation Society (ABAS), a grassroots group in Vancouver named after a Disney studio activist. Babbitt was among the highest-paid animators in Hollywood in the 1940s and a union leader of the Screen Cartoonists’ Guild. He spoke out against an issue still affecting animators today, an unfair pay structure. In his time, animators made anywhere between $12 and $300 a week. When studio boss Walt Disney personally fired Babbitt on May 28, 1941, because of his activism, more than 200 union members responded by going on strike.

Advocating for Animators

Most people employed in the entertainment industry are unionized — but not animators, game developers and artists in visual special effects. The Animation Guild in Los Angeles, Local 839 of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), is the exception, with 3,000 members working in more than 70 studios. Established in 1952, the Guild is rooted in labour disputes dating back to 1931, when animation was in its infancy. In 1937, workers signed on with the Commercial Artists and Designers Union (CADU) at the Fleischer Studios, best known for its Popeye and Betty Boop cartoons. When 15 employees were fired for union activities, Fleischer staff went on a five-month strike. The outcome was a historic first contract for animators. More union struggles followed. Animators were among thousands of American workers and activists impacted by the “Red Scare” of the post-war era, leading them in 1952 to charter Local 839 of IATSE.

So, after all this time, why haven’t artists in Canada organized?

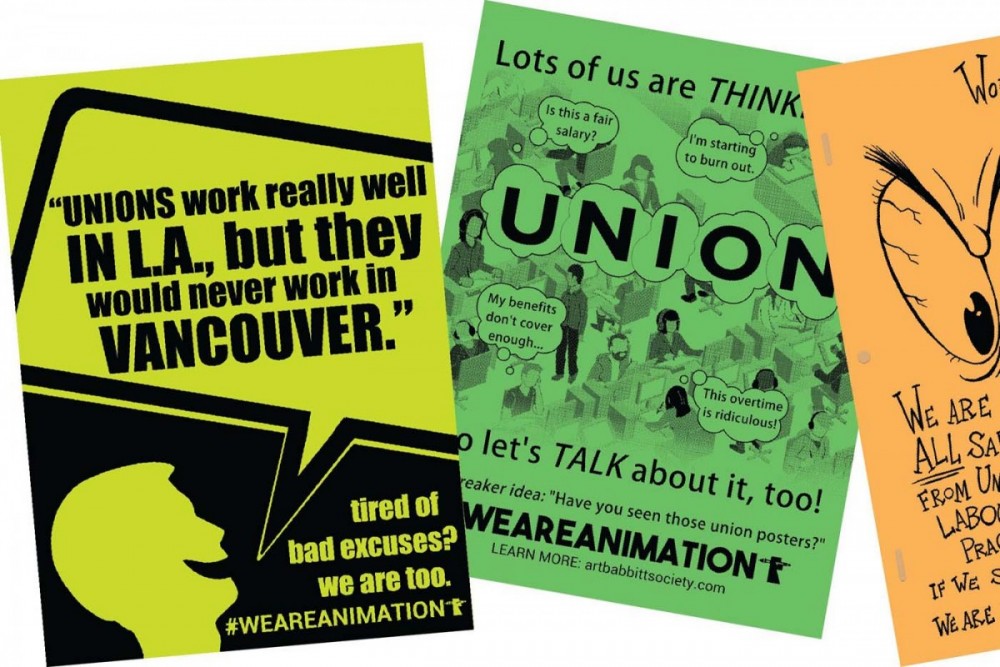

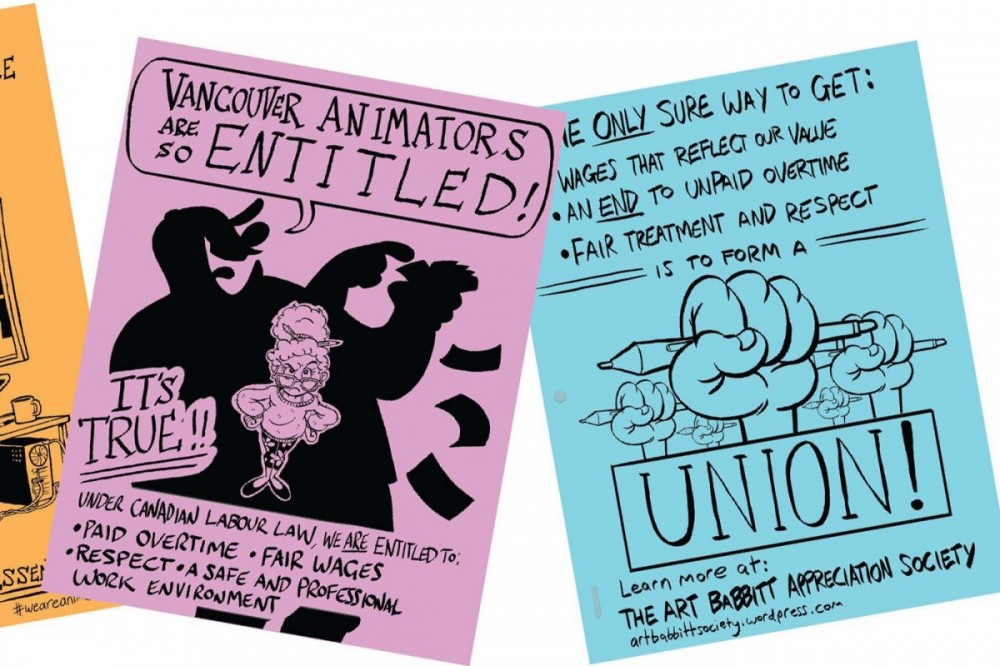

FLYER IMAGES: ABAS ORGANIZERS

Vanessa Kelly, along with union representatives for both IATSE International and the Media Union of BC, Local 2000 of Unifor, opens the studio door and gives us a look inside. Our Times also interviewed “Ken,” “Mark” and “Jane” — not their real names. All three are studio employees currently on contracts, and have requested anonymity.

“There is no future in this work,” says Ken, a special effects compositor for live-action effects in Vancouver. His work in visual effects (or “vfx”) involves using software to combine visual elements from separate sources into single images. Ken, at age 52, is an anomaly. Most studio artists “age out” by their late 30s due to low wages, lack of benefits and job instability. “You can make more as a barista,” Ken says. A cursory online search shows employers promise higher salaries than what they actually deliver: actual starting wages are barely above the BC minimum wage of $13.85 an hour. “A junior-intermediate artist makes $14.25 an hour,” Ken confirms. Contracts range from one year to 18 months and benefits are not guaranteed.

The “big six” studios, Warner Bros. Pictures, 20th Century Fox, Paramount Pictures, Universal Pictures, Sony Pictures Entertainment and Walt Disney Studios, do not hire artists directly. In the case of BC, seven companies with offices in the province bid for each studio contract, with the winning bidder then hiring the artists for that project. This system sometimes results in unrealistically low bids — and tight production budgets.

Ken has seen a lot of changes since getting his first contract after graduating from a fine arts program at a college in BC’s Fraser Valley in the 1990s. Artists are hired from around the world, he notes, and work on short-term contracts, moving from studio to studio. Those studios vary dramatically in size, employing anywhere from 200 to 1,500 workers.

British Columbia has been a favoured Canadian location for Hollywood studios since the 1990s, encouraged by BC government subsidies and legislation. While Vancouver is the main centre for animation and gaming studios, towns around the province benefit too, especially as set locations for filming live-action movies and TV shows. BC overtook Ontario for the title of “Hollywood North” when its film and TV production reached $3.6 billion in 2018, according to the Canadian Media Producers Association. The weaker Canadian dollar also provides an economic incentive. Travel from California to BC is convenient and in the same time zone.

“Vancouver has some of the best film schools in the world,” Ken says, citing Lost Boys Studios – School of Visual Effects, and Vancouver Film School. But tuition can be costly. Ken says that to mitigate this, some schools, like Masters School of 3D Animation, offer a 12-week introductory course, which allows potential students to see if the work suits them before they pay thousands of dollars in tuition for a two-year program.

He says though there were opportunities to organize a union as the number of vfx employees increased in the 1990s, that didn’t happen because these artists were considered outsiders. A division grew over the decade between unionized studio employees and this new occupational group. Unions were unaware of how integral vfx employees had become, Ken believes.

Coping with Precarity

Besides coping with precarious employment, artists are subject to employers’ creative demands, and often lack reasonable control over the work they produce. “The demanding schedules,” insists Vanessa, “take their toll artistically.”

Employees work long hours, especially during “crunch time” when there is a rush to finish a film project. “An employer could say ‘you must work Saturday and Sunday,’” Ken says, “and it’s up to the workers to say ‘I can’t.’” Employees usually don’t refuse because they’re seen as part of a team. “It’s hard to be the only one who gets up and leaves.”

“Employers have been known to fill out their employees’ time sheets without including overtime hours,” Vanessa says, “and even changing employees’ time sheets.”

She describes the burnout among artists. Vanessa herself has left the industry and now teaches cartooning classes to children. “Studios lose skilled workers all the time. There’s a high turnover rate. It stops animators from learning more.”

Pressure from studios to work faster and put in longer hours proliferates down the pipeline to animators who might have four days to do work that should take two weeks, Vanessa says. These pressures lead to all kinds of health issues, including anxiety and panic disorders.

Animators frequently work from dual monitors because of the amount of content involved. Long hours spent on two screens can lead to back strain and vision problems. Vanessa says she temporarily lost sight in one eye while employed as a storyboard artist. (After consulting a specialist, she purchased glasses and began performing eye exercises. Eventually, she recovered her sight.)

FLYER IMAGES: ABAS ORGANIZERS

Ken notes that technological change has also increased the sense of precarity and affected the quality of his work life. “It’s become assembly line work,” Ken says about vfx work. “Employees are increasingly easy to replace. The pipeline is changing as the technology changes,” he notes. “Jobs are being eliminated.”

He compares the trajectory of vfx work to that of desktop publishing. “At one time there was specialized equipment and training, and eventually it became more affordable and the pay was less and less.

“The job was different when I started. It was fun and creative. I had a passion for the work. Now the work has been deskilled. I’m professional, but the excitement isn’t there.”

Originally from France, Mark has been working as an animator in Vancouver for five years. Before that, he spent three years working in studios in England. As part of an animation team, he manipulates digital characters created by designers using commercial software. He moves or “animates” the figures on a drawing tablet and/or computer screen with a stylus or mouse.

While Mark has worked in digital special effects, he prefers animation. “I don’t see technology interfering with the skills needed for animators,” he says. “Special effects work is harder. There is more back and forth. You can work on something one to two months and have them [the supervisor or director] come back with ‘no.’ There are no limits to the back and forth.”

Of animation, Mark says, “The job itself is fun. Everyone enjoys it. It’s very rewarding to see people laugh in the theatre. We are passionate about the work and feel lucky to work in the industry.”

Passion and Pressure

Mark is critical, though, of how little control animators have over their work. When an animator completes their task, Mark says, the work is reviewed by the lead animator or supervisor. If it isn’t satisfactory, the animator receives written feedback. This process is repeated until the lead animator gives approval. The work then goes to the director, but if the director returns with notes, the animator must start again.

The employer, he says, can take advantage of an animator’s passion. Like Ken and Vanessa, he feels “It’s hard to balance artistic expectations and pressure, especially during crunch time.”

When it comes to actual sick days and vacations, studios paying for them sometimes lead employees to believe those days are “borrowed time” and that employees must make up for them by doing unpaid overtime, adds Vanessa.

That creates yet another stressor for animators. When Mark’s co-worker, for example, requested time off for surgery but became concerned the employer would fire him, Mark shared that concern: “I told him to save all his material [correspondence with the employer], in case of an unfair dismissal complaint.”

Still, not all employers are exploitative. Mark recalls receiving proper overtime pay at a small Vancouver studio. Another larger studio also paid him overtime, but did not follow the letter of the law, paying time and a half only after the first two hours of overtime had been worked. Mark acknowledges that when a studio does take advantage animators feel there’s little they can do. “You always hope the next contract will be better in terms of quality of work and conditions.”

Less Money, More Work

“I like the artistic part of the work and the problem solving. It’s a creative environment,” says Jane. With a background in graphic design, she has been an animator in Toronto since 2004, after working in studios in both Vancouver and Montreal. Her current position involves lighting and compositing — the final steps of the animation pipeline, as animators call the chain of production. After Jane’s work is complete, the director gives final approval and the film goes out to a company for grading and colouring.

“The main challenge is the budget,” she continues. There is less than needed, putting pressure on the workforce, with less time and money.” The story is a familiar one: “If you don’t want to do the overtime work, your contract might not be renewed.”

Companies also pay the individual artists they hire wildly different sums.

“There can be a discrepancy of up to $20 an hour,” Ken says about wage differences among highly skilled workers doing the exact same job but at different studios. The wage gap from top to bottom is glaring, too. Higher-end workers such as Ken can make $45 to $65 an hour, while junior animators make as low as $14.25 an hour.

In 2014, an anonymous group hacked Sony and posted, among other documents, the payroll information they found, Ken remembers. While widespread media reports drew attention to the hackers’ alleged intentions as well as Sony’s exposed contracts with top executives and celebrity actors, the files also revealed pay inequities among studio employees and blatant gender discrimination.

The workplace culture of paycheque secrecy — at all levels — serves the employer’s interests. “We don’t talk about wages,” Mark says. The Sony hack, in part, cut through that secrecy, Mark believes, and gave animators more leverage to bargain their contracts because they saw what was being negotiated.

Of gender discrimination in both BC and Ontario, Jane says the male-to-female employee ratio among animators is fairly equal but VFX work is male-dominated. “It’s more egalitarian in animation. In vfx, with more males, it’s a different dynamic.

“A sexist man (in charge) might not promote a female or give her good shots,” Jane adds.

Many employers, Mark observes, also readily exploit the vulnerabilities of those who aren’t yet established. “Armies of junior animators out of school are hired by some studios.”

Vanessa sees the same pattern. “Animators are hired out of school for depressed wages,” she notes. “It takes years to get a livable wage.” She estimates about 60 per cent of the workforce is made up of school graduates. “They haven’t developed the skills and speed. They are young and don’t know their labour rights.”

Taking advantage of workers coming into Canada is another huge issue. “There are lots of South Americans in one particular mid-size Vancouver studio,” Mark says. “They do a crazy amount of overtime. I would never go to that studio.” He says animators there quit as soon as they receive a permanent residency card.

Jane agrees that, though employees are diverse, they are not always treated equally. “I have seen some people hired on visas and paid less.”

Though most animators are young, Jane notes that supervisors can be over 35. “It’s a pyramid like any other industry,” she says, and “the base does fill up with younger, cheaper animators just out of school.”

Sausage Party No Party to Make

In 2016, the film Sausage Party was released. Co-written and produced by Canadian-born actor Seth Rogen, with BC’s Nitrogen Studios managing the animation, it was a box office hit, grossing $140.7 million and becoming the highest grossing R-rated animation film in history.

With large doses of dark humour, the made-for-adults film tells the story of a sausage named Frank living in a supermarket who goes on a journey with his friends — a bun, a taco and a bagel — to escape their fate as someone’s next meal. In doing so, Frank faces his nemesis, who wants to kill the four friends. Praise was showered on the high-quality animation, delivered on an uncommonly low budget, but it seems the cost-cutting was at least partially done on the backs of animators.

During the project, animators went through a challenging journey which included a real-life nemesis, not unlike the one in the story they were drawing. Troubles developed, with as many as 30 animators quitting because they were forced to work unpaid overtime, given impossible deadlines, and subjected to a toxic environment created by a threatening supervisor.

Any employee’s refusal to work unpaid overtime allegedly led the supervisor to repeatedly threaten to reassign their work to someone who would stay late. The same supervisor also threatened to terminate employees and block any chance of their being hired in the future across the industry.

About 20 of the animators hired to replace those who had quit continued to protest the unfair conditions, writing a letter to the employer. “We tried to word the letter in a reasonable way and to be positive,” Mark, who was one of those newly hired animators, says. “We also talked about loving the movie and our work.”

The group detailed their experiences of unpaid overtime and of being subjected to “pressure and scare tactics.” The letter was not well-received. But when a copy was given to co-producer Annapurna Pictures, a representative interceded and made sure the animators got paid. “It was an exceptional case,” Mark says, though negative feelings lingered. “Many of the 20 people involved have left Vancouver and many who didn’t work to the end of the project didn’t get credit (on the film) and were upset.”

In 2000, the BC government introduced a change to the Employment Standards Act (ESA), excluding “high technology professionals” from receiving overtime pay. The provision has long been seen as a loophole which allows employers in the high-tech industry, as well as others, to exploit workers. But the definition of these professionals in the Act was challenged in 2017 when Jennifer Moreau, secretary-treasurer of Unifor Local 2000, filed a third-party complaint with the province’s Employment Standards Branch after learning about the treatment of the Sausage Party animators. Some of these former employees had commented anonymously online about their experience, drawing Jennifer’s attention and motivating her to make the third-party complaint.

Jennifer Moreau, secretary-treasurer of Unifor Local 2000, filed a complaint with BC’s Employment Standards Branch after learning about the poor treatment of animators working on the film Sausage Party. PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY JENNIFER MOREAU

It took until early spring of this year for the ruling to come down: Animators, special-effects and gaming employees are not “high tech professionals” and cannot be excluded from receiving overtime pay. Nitrogen, now Cinesite Studios, was instructed to open its books and pay the animators overtime, but records had not been kept by either the employer or employees, so no payouts have been made to date, according to Jennifer.

Still she says the decision was important. “The studios will have to think twice before claiming their employees are high-tech and ineligible for overtime,” she stated in a media release in March.

So what will be the tipping point that leads artists in Canada to join a union?

Organizing studio artists is like “catching water with a net,” Ken believes, because the work is migratory.

“There isn’t leverage (among employees). The digital industry is portable. They could move to Mumbai or anywhere else in the world.”

It’s a fear that has played out on a global scale in many industries. In 2013, for instance, Disney shut down its Pixar Canada animation studio in Vancouver, laying off 100 people and moving its work to Emeryville, California.

Ken admits a union would be a “great idea,” pointing to the opportunity for job stability. “Wages are standardized; there are benefits and the shaping of the industry [by union members],” he acknowledges. He wonders, though, who will protect workers trying to form a union, and what a union model would look like.

Mark agrees with Ken that animators come and go, and that forming a union would be difficult. He observes people are scared, too. “The UK has some momentum to organize,” he says about his previous work location, where overtime was also a major issue. “They are further ahead than here.

“Animators have a lack of education about unions,” Mark believes. “They don’t know their rights.” He thinks it is a good idea for a union representative to visit an animation school in Vancouver and talk about unions, especially since these students are vulnerable to exploitation when they enter the workplace. Unifor approached a school for this purpose, Mark says, but was turned down.

Animators in Toronto, like Jane, are also not optimistic about a union being able to organize workers there. Since animation studios started emerging, “there’s been so much anti-union propaganda, even saying the word ‘union,’” she says. “People have a negative attitude. Lots have a positive attitude, but not enough to make a shift. I don’t see it happening.”

Still, she sees some form of change as inevitable.

“As more women enter animation and the industry grows up, people will want to have families and go home to their families. They will push back so they don’t have to do long hours at the behest of the employer.”

The Time is Right to Organize

After volunteering with ABAS for three years, Vanessa believes the time is right to organize. “When studios first opened in Vancouver, we saw this as a gift from Los Angeles,” she says. “There was a palpable fear that if we join a union, the studios will pull out and the industry will collapse.”

The studio scene was much smaller 20 years ago, Vanessa also notes. “Now it’s so large and so integral to the entertainment process that animators are starting to realize our value. So to pick up and move would be a massive cost. I don’t believe the studios will take that risk.”

She is confident workers will unite, despite the transient nature of their work. “If we work collectively, we can succeed. We work in teams (on the job) and know each other. We go to social events all the time. This is a network-based industry.”

Unifor Local 2000 has been trying to organize vfx artists, animators and gamers in Vancouver for more than 10 years. “There’s a reluctance to be a leader in an organizing drive,” Jennifer Moreau observes. “There’s also a generational disconnect. We [unions] don’t have representation of young workers.” Despite the challenges, she has cultivated strong relationships with several studio artists in Vancouver and is hopeful workers will sign union cards when the time is right.

Artists became dramatically more aware of unions when Unifor Local 2000 delivered the legal win on the overtime issue this year. And when Jennifer followed up by posting an anonymous online survey, she received a hundred responses from animation, special-effects and video-game employees in Vancouver, only six per cent of them over 40 years old. More than half were interested in joining a union “but unsure what it would mean,” while about 20 per cent were ready to sign a union card.

Job Instability, Poor Management

The top three workplace complaints people listed on the survey were job instability, poor management and long hours with unpaid overtime. Additional comments from respondents included a desire for studios to have “better management, especially around scheduling realistic deadlines, and better coordination, planning and communication.” Also noted was a desire for “improved pay” and “transparency around wages.”

One respondent called for companies to “push back against unrealistic client demands and the fixed bid process, where studios undercut each other at the workers’ expense.” A few raised issues such as child care and sexual harassment. The lack of paid sick days was also noted.

Meantime, Vanessa has joined forces with Julia Neville, international representative of IATSE, from an office in downtown Vancouver. The pair issued a press release this past July, stating ABAS and IATSE “have formalized a strategic alliance in efforts to unionize animation workers in Canada.”

Vanessa had already established an annual “Animation Wage Share” online survey. In the 2017 wage-share results posted online, she showed data from 676 respondents residing in eight provinces, including BC. Slightly more females than males responded, 30 per cent from visible minorities. Sixty-one per cent worked overtime and of this group, 66 per cent said they were not paid, an employer practice Vanessa calls wage theft.

Vanessa’s collaboration with Julia, a former technician and production manager and a member of the Directors Guild of Canada, effectively brings together two organizers with studio experience. Julia says “work-life balance” is an issue across the entertainment industry. She’s hopeful “We can impose penalties,” through union contracts, “and make cost [of overtime pay] a factor, hoping this impacts project schedules.

Change is Coming

“Animators used to be scared to be seen talking at our IATSE booth at conventions,” Julia also says, noting this has changed as unions continue to focus on reaching out to all workers. She points to the success of the Fight for $15 campaign to raise the minimum wage across North America and the campaign’s union supporters. “The educational level around unions has grown and there is more positive public discourse,” Julia believes.

As things are now, some artists are so traumatized from their experiences in the industry Vanessa says, they eventually transition into completely different careers.

“To take an artist’s passion and take advantage is hard to swallow. It’s a testament to our skills that we have won Oscars under horrific and exploitative conditions.”

With the many benefits of a union, animators will stay longer in the industry and develop their skills, she predicts. And then the sky’s the limit.

“We will be the best in the world,” Vanessa says. “We are going to ‘wow’ the world.”

Janet Nicol is a Vancouver-based freelance writer and regular blogger.