Arranging an interview with Tanya Ferguson involves a little scheduling. When first contacted, she's travelling back home from the United States; a few days later, she's out of town and apologetic because she's committed to helping with a collective-bargaining class at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario.

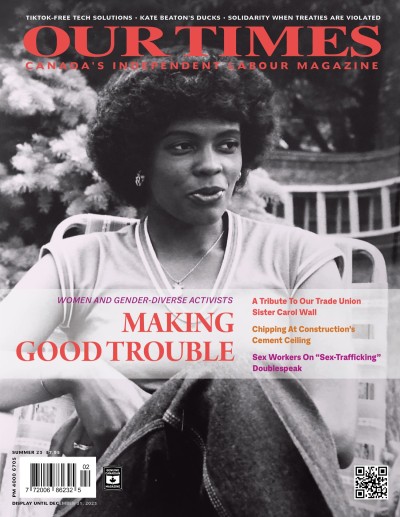

It's on a Friday evening, when many of her peers would be unwinding at a bar or in front of the television, that Tanya finally has a moment to chat with me for Our Times. This advisory member of the Our Times board is nothing if not busy and dedicated.

"My friend teaches collective-bargaining formulation and I've always gone every year," explains the organizing coordinator for Workers United Canada. "The students actually have an assignment where they have to get a collective agreement by the end of their semester, so you're supposed to stay and be a resource for them."

KNOCKING AT THE DOOR

Ferguson has been a logical choice to help with the exercise over the past few years: she has worked for Workers United and its affiliates for the better part of a decade. "We have, at this point, five staff organizers, and then I coordinate our programs," she says of her position. "Our organizers do work with people who are non-union, who we're trying to help organize into a union, and we often work with our existing members to do that, so I'm at work sites at least once a week. We have an office downtown, but it's not really an office job."

Workers United Canada is a union in which members and issues come from both traditional and non-traditional sectors. Though it began by organizing in the clothing and textile industry, the union now also represents workers in social service organizations, restaurants, hotels, the retail sector, and in manufacturing and distribution. And the diversity of occupations represented only continues to grow.

When it comes to how workers in these often-marginalized occupations initially get in touch with Workers United, Ferguson says some respond to union outreach while others initiate contact themselves: "We have people calling our office and, you know, we run with those often. But we also have our own strategic targets in sectors where we want to grow, or there are employers where we represent the members at some locations but not others. But we also have people knocking at our door, like a recycling facility out in Mississauga that wanted to form a union, and they contacted us. We had somebody at a Starbucks café in downtown Toronto who contacted us. GoodLife instructors and trainers — we're working with them right now."

The organizing effort at GoodLife Fitness took even Ferguson a little by surprise. "That is something that totally would not have been on our radar at all, but they got in touch with us and they're trying to form a union," she reports.

KEEPING CLOSE TO THE GROUND

Organizing in precarious occupational sectors like those represented by Workers United is no easy feat. "Basically, we walk people through what the steps are legally, and then we walk people through what it takes to organize their co-workers, because most people have the impression that if they have majority, there are laws in place to sort of take them from A to Z," she cautions. "But a lot of times with union organizing, it's completely underground, so people have to know all the risks involved and do all the groundwork: trying to map out the workplace; trying to find out what issues people outside their own department have; trying to find out if they truly do have the support of people in their workplace, beyond their friends."

Her role is to offer support and information by "coaching" throughout the process, but also by "inoculating" employees to withstand unpleasant, even threatening, actions by employers or co-workers who disagree with their organizing efforts.

Day to day, Ferguson's routine includes "getting out there and talking to the people who our committee doesn't have contact with or who don't yet trust us. It's a lot of follow-up."

She was a staff organizer before she became a coordinator with Workers United, a role she calls enjoyable due to its broad scope. Every staff role and elected role there has "worker outreach" built into the job. That expectation suits Ferguson fine, since she admits she appreciates all aspects of helping workplaces organize.

"In the early stages, I think that the big picture is more fun, because you get to step back and see all the potential, but once you get closer to running a campaign or getting to a vote, the closer you are to the ground, the more rewarding it is."

GETTING TO KNOW LABOUR

She initially became involved with Workers United when hired as an intern in 2002. The union was doing outreach at York University because Marriott, the provider of campus food services, had controversial investments in private American prisons. She was a York University Black Students' Alliance (YUBSA) member-at-large who was already working on that specific campaign.

"The Black students' association was really critical about it because of the number of African-Americans in the U.S. who are in these private prisons," Ferguson explains. "So the union reached out to us, and I applied for this internship. And I found out exactly what organizing was." She was 20.

Even though she grew up in a family in which one of her parents (her mother) belonged to a union, and she had worked in unionized positions herself as a teenager, Ferguson recalls not really understanding their relevance until years later. Her internship with Workers United Canada changed her relationship with unions. "I was active at an early age, through high school and stuff, but I didn't really have any knowledge of unions or where the labour piece fit in," Ferguson elaborates. "I had been a union member, at that point, for at least five years."

THE TURNING POINT

Working at a hospital and a grocery store didn't educate her on the larger labour movement or the specifics of personal involvement in her own union, a contradiction she says still puzzles her today. "I had zero knowledge of it. I often reflect on that now and say, 'How was that possible?!' I've worked since I was 14. I think my first union job, I was 15, and after that, I was always in a union, and it wasn't by choice."

After all, Ferguson says it was very clear that when her mother joined a union, the family's life changed for the better. Her parents immigrated to Canada from Grenada before she was born. Her mother worked in a Newmarket, Ontario, nursing home as a personal care worker, always on call, before her employment conditions improved significantly when she was hired for a related position in a hospital.

"She became happier and was earning more," remembers Ferguson. "When she became a union member, she did tell us it was a positive thing. We saw the changes in our life, when she went from a bad job to a good job. I think we all look back and see that was kind of a turning point, for our family."

EYEWITNESS TO INJUSTICE

She admits that both her parents were skeptical when she took her first organizing job. They didn't fully understand what their daughter's work entailed, or why she worked such long hours.

"Now they've both been out to picket lines and they've heard all the stories and see that it's part of my life, and they appreciate it. Our whole family has seen how people have struggled with being treated unfairly at work, so I think there's a different appreciation for it now," says Ferguson. "As a family, we can see a difference between being in a union and not being in a union."

Her father found out firsthand, after being laid off, in 2009, from the job he had held since coming to Canada. He had worked as a press operator in a print shop at Quebecor Printing for 30 years, during which a few unsuccessful attempts had been made to unionize the Quebecor workplace.

"We always have these political debates in our family, and back then, my dad was always like, 'Unions are outdated.' But after going through that, he saw that it's the typical story where you think you have more protections than you do, and you're just at the whim of the company," offers Ferguson. "It's just a whole different economy than it was when he started working at Quebecor." Her father is now a unionized printing press operator at the Toronto Star. "I think my dad today is more pro-union than any of us, because he's seen so many injustices."

CLiFF CAN CHANGE THE WORLD

Tanya Ferguson sits on the board of the Canadian Labour International Film Festival (CLiFF). She joined nearly four years ago, after a fellow member of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists resigned.

"Once I got involved, I really liked it — I like the group of people that are running CLiFF and what they're trying to do," she says, adding that one film, Betrayed: The Story of Canadian Merchant Seamen, spoke to her with particular strength.

Produced and directed by documentary filmmaker/photographer Elaine Brière, the film tells the story of the Canadian Seaman's Union (CSU), which won the eight-hour day, sick leave and pay increases for seafarers. "It was such a simple and great way to explain. Why, for example, did I not even know I was in a union as a teenager? I was taught by union members for 20 years — didn't even know what a union did! It's just so hard to explain big concepts, so when I saw this movie, I felt like, 'This is perfect!'

Tanya Ferguson with fellow CLiFF board member Frank Saptel. PHOTOGRAPH: LORRAINE ENDICOTT

"We need movies about unions or the labour movement that people have occasion to sit and watch, movies that are well done and interesting." Not a filmmaker herself, Ferguson says she values the way a good film can share a message or provoke critical thinking among diverse and far-flung audiences.

"In the past, I've helped with the logistics, sent the DVDs out [to screen at venues across Canada] — at most locations we can't rely on people being able to screen movies, because of internet-access issues and things like that, so there's quite a lot of logistical work, fundraising and promotions."

Submissions for the latest CLiFF competition have been steadily coming in, notes Ferguson. About half of the entries so far have made it into the current festival. This year, because of technical improvements introduced by new board member and working filmmaker Scott MacDonald, CLiFF can accept online submissions and make DVD-free screenings possible.

NEVER ENOUGH TIME

With her tendency to overextend herself in her passionate support of social justice, Ferguson has recently had to step back from a few commitments. Doing work for the organization Justice for Migrant Workers, for instance, is something she misses.

"I was able to balance it better before than I do now," she sighs. "There's just not enough time." When she and her parents lived in the agricultural community of Bradford, Ontario, she was more able to participate. "In the past I helped with going out to some of the workplaces and the farms, reaching out to migrant farm workers," explains Ferguson.

"I started taking some courses in adult education and health and safety. I started them several times and then I dropped them, and for me, it's just 'stop wasting tuition money,' on dropping things halfway through," she admits. "I haven't been able to manage my personal goals, along with everything else. I need to make room for people that I want to see."

It's no minor adjustment for a woman who, not that long ago, moved to California to help a large public sector union there, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), with a strike, for three years.

"I had worked on campaigns in the U.S. and I thought that I would like it," she explains. "It was University of California workers and it was beautiful when I went out there. I fell in love with California." The strike involved workers at the University's teaching hospitals, as well as cafeteria workers, janitors, groundskeepers and other people employed in campus-based services.

THE PERFECT LEARNING GROUND

Despite all her previous union experience, the situation was an eye-opener, in a positive way. "It was like the perfect learning ground, because that local union, they had a model where there was an organizer and a rep, so I got to learn everything all at once: I got to learn about contract negotiations, about contract fights, about representing workers, while still doing organizing. It was a three-year campaign; first we had to get workers paying into a strike fund and then we had to start building the story about what kind of changes could be in this contract. Then, we went on strike."

Ferguson says the University of California employees fought for wages based on a campaign they called "Steps," which promoted a fair, graduated pay scale, as opposed to the favouritism they witnessed in the workplace. "We were successful in getting that."

California has a "Fair Share Law," whereby workers who are represented by a union, but who have not paid dues to or joined that union, must still pay it a "fair share fee." An infusion of money under this law made it possible for AFSCME to undertake the battle.

The Workers United organizing coordinator expresses admiration for the rank-and-file union leadership and workers involved, as well as the students who supported the unionized employees: "These are people who committed to a multi-year campaign, and they saw it through. I still get their email blast, and they're doing good work out there."

TAKING THE TIME TO GROW

A bad experience with some intra-union conflict and six unenjoyable months of working in Michigan convinced Ferguson that she wanted to be organizing, not embroiled in internal politics surrounding existing members. The Toronto resident left Michigan and returned to work as a union representative with nursing home workers, with the Service Employees Union International (SEIU). "It was fun, but I liked the organizing," says Ferguson of her time there. "UNITE was always my home, it's where I wanted to be," she notes, naming the union that was the precursor to Workers United.

A director invited her to return and take a position with Workers United; she accepted. That was three years ago. Ferguson says she loves being actively involved with strategy and rebuilding the union "from scratch" with former colleagues. "I feel really lucky this time, because I feel I can take the time to grow, personally. That's something that I am learning is really important. It's just an interesting time to be organizing again."

The saying "may you live in interesting times" comes to mind — the word interesting suggestive of something unpleasant or difficult, like many workers' experiences in the Canadian economy of 2015. But there's no irony when the organizing coordinator voices genuine interest in what she does. "People are calling you from all walks of life. Taxi drivers calling our office, fitness instructors calling our office. It's amazing."

SEEING THE SIGNS

There are encouraging signs. Ferguson mentions "more of a shared knowledge of the presence of sexism" in the workplace today, for instance. On the negative side, she's been hearing about the increasing number of people with no workers' compensation coverage (overseen in Ontario by the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board). "I don't remember ever coming across that until recently," she notes. "The number of workplaces that seem to be excluded, that's new to me."

Outdated job descriptions encompassed by the Ontario Workers' Compensation Act mean that unless someone has benefits through a second job elsewhere, they are without insurance for workplace injuries, even in very physical and dangerous jobs.

"Even if the employer says, 'Yes, we'll hold your job,' they are going to make it very difficult for that person to come back to work, because you're not going to be fully recovered and healthy," she argues. "On the books it looks like you have a job, but if you can't actually go and work. . . ."

A MATTER OF RESPECT

Respect is another subject she hears about on the frontlines. "When they're not being treated respectfully at work, that's when people want to organize and stick together," Ferguson says, citing the case of Mississauga recycling depot workers. "They're not minimum wage workers, but they would have contractors or delivery people come into their workplace, who were union members, who would hear the way their supervisor spoke to them and say 'You guys should form a union' or 'They wouldn't speak to you that way if you had a union.'"

Another, non-union, workplace, which she cannot name due to ongoing problems there, saw a new manager harassing older workers, especially those of Caribbean descent, into quitting. "They had all these stories, 'This is an Army guy, this is why he talks to us this way,' and a lot of the workers felt that he was intentionally pushing them out."

Workers United also just organized community-based health care providers in Simcoe, Ontario, who complained of receiving zero feedback about their clients' health between visits. Again, observes Ferguson, a matter of (dis)respect: "The families respect them; their employer doesn't."

EQUITY UNREALIZED

Ferguson notes that racism and class oppression are just two of the forces preventing real democratization of the labour movement. Workers are not yet fully entrusted with control of the movement; historic blights linger as a result.

"I'm not an expert, but my experience with 'equity' in our movement is that it is an invitation to fit into a box: 'Workers of Colour and Aboriginal Workers' — most people I know don't fit into these structures easily. In fact, the most memorable and motivating moments I've been a part of have happened outside of these structures."

She suggests that democratization could radically address pervasive exclusions: "We would find a way to fix the anti-Black racism that keeps so many young Black people out of jobs. And we would find a way to include First Nations people who are not nearly visible enough in our movement."

Ferguson is adamant that leaving people of colour out of most significant roles in organized labour hurts everyone. "Over the past decade, I have worked with so many brilliant organizers — almost all people of colour who are completely loyal to the union and gifted at their jobs. But in our current movement, these people will probably never have any meaningful influence," she explains.

"In turn, the new members they recruit will probably not have real influence and power. They are mostly used by the union to communicate with fellow workers in their various languages and to increase membership. That needs to change, too."

Such tokenism is a serious problem Ferguson identifies as undermining the real contributions of so-called minorities and reinforcing the status quo in the process: "Too many times, I've seen a coloured face standing beside a white person; the white person is probably the one who has most of the power and influence in their local union."

MAKING UNIONS PERSONAL

After 15 years of involvement with organized labour, the Toronto resident reflects that experiencing unions from the perspective of a staff member has been "far more interesting and more memorable" to her than her time as a young union member.

Ferguson suggests changes presently happening in the movement can make the union experience more personal for others, particularly workers looking to organize in unconventional lines of work.

"As a staff person, I came in through internships that were designed to recruit organizers, so I've always been part of unions that have a strong organizing culture. UNITE, SEIU, UNITE HERE and now Workers United (I'm sure there are a lot more): these unions really support workers who want to form a union. I think that's brilliant. There is such an unrelenting support for workers who want to stick together and organize, within the culture of a lot of unions, and that's amazing."

PHOTOGRAPH: LORRAINE ENDICOTT

Intelligently critiquing the movement will also help to revitalize it. "There is a growing pro-union, yet critical, voice that is good for our movement," observes Ferguson. "In the U.S. there's Labor Notes, and now we have rankandfile.ca in Canada. These are voices that are pro-union and independent from the union bureaucracy. They inject accountability and keep things interesting."

Listening to temps, migrant workers, unemployed people and employees in unconventional workplaces also brings valuable input to the table. "There are still too many workers who are excluded from the union movement," argues the insightful organizer. "Lots of people are organizing anyway, but we need to figure out how to unify."

What would it take to cultivate greater unity among existing union members? Ferguson says listening to members' concerns and maintaining transparency are essential.

"In our current structure, workers who have problems or perceived problems with their union structure sometimes end up trying to decertify, or they get persuaded into a raid position. Our current structure has no transparent system that takes the concerns of union members seriously."

Even when complaints originate from "puppets for management" or members simply lacking a well-developed understanding of political ideology, they should not be casually dismissed. "Unions can be a giant force for good," she stresses. "I think it's damaging that dissenters end up at the labour board, or entertaining decertifications, or with 'rat unions.'"

MORE AMBITIOUS GOALS

Not every effort meets with long-term success. Ferguson describes one manufacturing facility that organized, but then closed, in 2014.

"There are places where we are losing jobs; there's no way to get around it," she says of the changing landscape of Canadian work. Yet some communities possess a cultural climate she associates with understanding the role of unions and how they assist in hard times. The organizing coordinator says she encountered this attitude during her six months in Detroit. She says she met plenty of people who "get it" there. "Not everybody clings to the explanation that 'unions aren't doing enough'" to preserve jobs, argues Ferguson.

"My own family's experience was 'It's too bad that Dad had to go through that alone, without an organization behind him' when he was laid off, because if that was my mom, she's at a hospital and everyone's in the union, and it would be a whole different scene."

The "scene" could go further if unions reached a wider audience with their message. "I think unions are the only organizations that truly have the power to engage in widespread political education. This is severely lacking," the thoughtful activist points out. "Unions are in a unique position to educate workers and the broader public about the history of this economy. If we trained frontline stewards, staff reps and organizers about the history of our economy and the lessons of social movements, we would have much more ambitious goals, for a world without racism and poverty."

Though many Canadian manufacturing jobs have been moved overseas, to nations with abysmally low standards for wages and workers' rights, Ferguson observes an emerging trend: "There is a small niche market for high-end stuff that's being made in Canada again," such as Canada Goose parkas. Garment workers with that company, incidentally, have long been represented by Workers United Canada.

"As much as some places are closing their doors, other doors are opening," she says with conviction. Ferguson could be speaking about workers in the manufacturing sector, about the labour movement, or about her own life. Her words apply to all three.

Melissa Keith is a former radio broadcaster and an award-winning freelance journalist. She lives in Lower Sackville, Nova Scotia.