"We want to ensure that the new green economy is inclusive of racialized people," says Christopher Wilson, a member of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists (CBTU), and Ontario regional coordinator for the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC). "Climate change is at the forefront of a number of policy discussions, and we want to be part of that process. If we're not, the transition to a new green economy is not going to be just, and we're going be left on the margins."

Wilson, along with PSAC Ontario union negotiator Jawara Gairey, is leading a groundbreaking research project called Environmental Racism: The Impact of Climate Change on Racialized Canadian Communities: An Environmental Justice Perspective. The initiative was launched in 2017 by York University's ACW project, in collaboration with CBTU. Adapting Canadian Work and Workplaces to Respond to Climate Change (ACW) itself grew out of the university's Work in a Warming World research program, founded and headed by professor Carla Lipsig-Mummé.

“We’re very much inspired by the Idle No More movement and activism among Indigenous peoples who protect the water, protect the earth, protect treaty rights,” says Christopher Wilson. PHOTOGRAPH: ROSE HA/ PHOTOGRAPHY FOR SOCIAL GOOD

REDUCING RACIAL INCOME INEQUALITY

"It's an action-research project meant to equip Black trade unionists and racialized activists with the tools they need to influence the public-policy debate over climate change," says Wilson.

"So what we've been using as a framework for our project is the fact that you're seeing a lot of discussion, a lot of policy commitments at a national and provincial level, about reducing greenhouse gas emissions and slowing climate change, but not necessarily linking that analysis to reducing structural and racial income inequality."

According to Wilson and Gairey the subject of environmental racism is a dramatically under-researched topic in this country, despite being a longstanding issue. But there are those, like Ingrid Waldron, an associate professor at Dalhousie University, who have been working to change that.

INEQUALITY AFFECTS HEALTH

Waldron explores how inequity and discrimination impact the health, both mental and physical, of Indigenous and racialized communities in Canada. She also focuses on the social determinants of health in Black and immigrant communities in Halifax.

Her new book, There's Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous and Black Communities (Fernwood), highlights the grassroots resistance against environmental racism and uses Nova Scotia as a case study to examine how environmental toxins have been disproportionately stored and released within racialized communities.

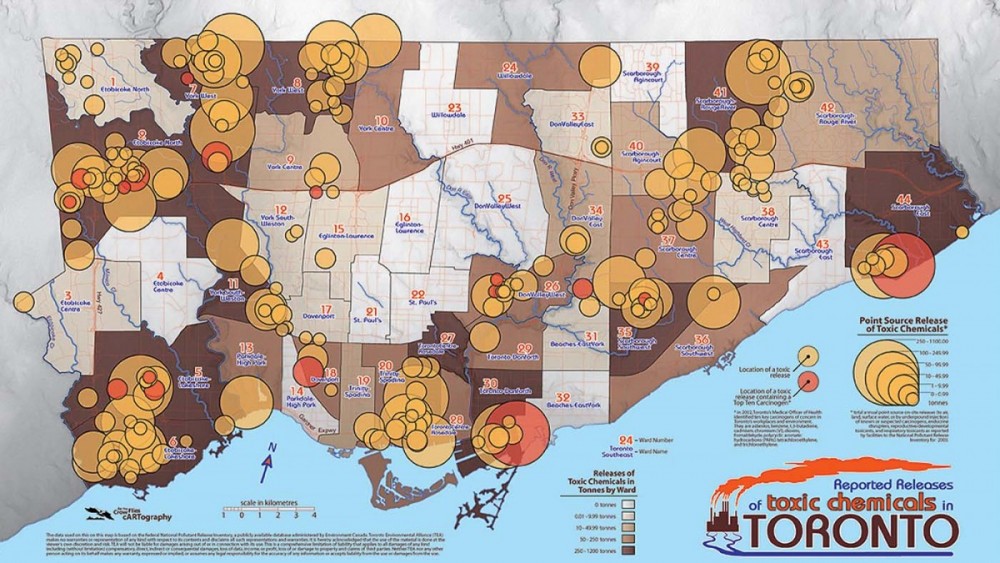

Wilson and Gairey also point to the work of the Toronto Environmental Alliance (TEA). The group's 2005 Toxics in Toronto Map illustrates the reported releases during 2003 of over 7,000 tonnes of toxic chemicals in the Greater Toronto Area. The map serves as stark visual evidence of the correlation between levels of air pollution and the location of racialized communities. Part of TEA's "Secrecy is Toxic Campaign," the map was used as a tool by community members to press their local city councillors for stronger legislation around pollutants.

MAP: COURTESY TORONTO ENVIRONMENTAL ALLIANCE

There are countless examples of environmental racism in Canada. In Northwestern Ontario, mercury leaking from a long-shuttered paper mill has been poisoning the Grassy Narrows First Nation community for over 50 years.

Aamjiwnaang Nation struggles with heavy air pollution from Southern Ontario's Chemical Valley. (Located in Sarnia, Chemical Valley is home to more than 60 plants and refineries that release millions of kilograms of air pollution each year.)

In Northeastern Alberta the Athabasca Oil Sands leak toxic residue into the Athabasca River, profoundly affecting the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation. And Shoal Lake 40, a community on the border of Manitoba and Ontario that was cut off from land access 100 years ago to build an aqueduct carrying fresh drinking water to Winnipeg, has, ironically, remained under a boil-water advisory for over two decades. Shoal Lake 40 is only one of many Indigenous communities under boil-water advisories throughout the country.

Gentrification, air pollution and other toxins are also disproportionately affecting racialized communities in Canada.

RAISING AWARENESS, ENGAGING IN STRUGGLE

The Environmental Racism Project aims to change all that. The main goals of the project, as articulated by Wilson, include:

* Raising awareness on how environmental racism is having a disproportionate impact on racialized communities

* Talking about how climate change can serve as a catalyst for social change

* Talking about public policy commitments to climate change

* Exploring what kind of responses to climate change have come from the labour movement

* Creating spaces for racialized communities to engage in the struggle

* Talking about developing strategies so a "just transition" is inclusive of racialized workers.

"Just transition" is a central theme of the project and ensuring the roles, policies and practices created during this transition are inclusive of racialized communities is one of its chief aims.

CLIMATE CHANGE AS A SOCIAL CATALYST

"Climate change can serve as a social catalyst through the creation of new economic opportunities for Canada's racialized communities," explains Wilson. "But if we're not active, the transition to a green economy will again leave us on the margins. The way we say it is: we don't want the new green economy to look like the old white economy."

The first phase of the participatory research project included research led by Carla Lipsig-Mummé, as well as a review of that research, both of which are now completed. "Participatory research as a methodology is based on the popular education model used within the labour movement and the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists," says Wilson.

The objective is to engage people in a co-learning process: "The experiences of participants are integral to the learning and research processes." And those experiences help shape which concrete actions will then be taken in the fight for environmental justice.

The second phase, designing and facilitating workshops, is now underway, with the project recently receiving the funding to develop a full-day workshop. The goal is "to develop activists from racialized communities in the environmental justice movement by giving participatory workshops on the topic of environmental racism," Wilson continues. The first of these was a half-day workshop presented by Gairey, in December 2017, to the Elementary Teachers of Toronto (ETT).

With the Environmental Racism Project “we want to ensure ‘boots on the ground,’” says Jawara Gairey. “We’re really pushing for structural change within our communities.” PHOTOGRAPH: ROSE HA/ PHOTOGRAPHY FOR SOCIAL GOOD

TORONTO TEACHERS TAKE FIRST WORKSHOP

Forty members of ETT attended the first session, which included a presentation by Gairey, interactive activities with participants and feedback to be used in the development of future workshops. Participants also submitted their own ideas for "creating intentional action" with their students.

According to Gairey's summary of the workshop, the teachers offered ideas like teaching children to grow food gardens at school, promoting local consumption practices, and creating free cycling hubs so children could commute to school. They also suggested developing strategies to equip racialized students from Kindergarten to Grade 8 with the skills needed to participate in the green economy.

Wilson notes that the team intends to make the facilitation notes public through the ACW website so that labour unions and community organizations can engage their members and communities in the struggle.

"A lot of times this academic research is done and then the policy papers or whatever just sit on the shelf," says Gairey. "Used as a sort of footnote in the next big paper, but we want to ensure 'boots on the ground;' we're really pushing for structural change within our communities."

ENGAGING THE LABOUR MOVEMENT

According to Wilson and Gairey, the labour movement can be integral to this effort. "The Canadian labour movement represents four million workers across Canada and plays a key role in shaping, or having a voice in, the economy. So our hope is that by engaging our community, by engaging the labour movement, we can effect change and reduce racial income inequality. We're trying to work from our strengths, to where we can make a difference.

"Unions also play a key role in shaping workplace policies, including policies intended to facilitate and support diversity and racial equality," Wilson explains. Additionally, unions can play a major part in implementing greener policies in workplaces.

For example, through the collective bargaining process: "One of the initiatives of the ACW project is to develop a database of contract language speaking to climate change. And we intend to add to that database by adding clauses that specifically speak to environmental racism."

COALITION OF BLACK TRADE UNIONISTS

According to Wilson, CBTU, which has members in both Canada and the United States, is uniquely situated to lead this kind of initiative and this kind of advocacy. "CBTU is rooted in community, in the Black community, in a way that no other affiliated union is. We have a specific mandate to give voice to Black trade unionists, so CBTU is well positioned to engage Black trade unionists in this struggle. That's one advantage and that's one of the objectives of this action research project.

Christopher Wilson (left) and Nigel Barriffe, president of the Urban Alliance on Race Relations, at the Toronto People’s Climate March in April 2017. PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY CHRISTOPHER WILSON

"Members of CBTU are also members of affiliated unions across Canada, including of all the major affiliates. We also have members who work for the central labour bodies, including the Ontario Federation of Labour and the Canadian Labour Congress, both of whom are partners in the ACW research project. So what we intend to do in CBTU is to leverage those connections."

CBTU has also worked with a number of partner organizations like the Asian Canadian Labour Alliance (ACLA) and the Latin American Trade Unionists Coalition (LATUC). According to Wilson and Gairey, CBTU intends to continue building on connections with these and other organizations, specifically those that represent workers in racialized communities in Canada, and engage them in the project's environmental racism workshops, to help supply the tools to conduct advocacy.

"In very practical terms, the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists is intended to create a space for trade unionists who self-identify as of African descent or Black; that will very much play a focus within our analysis and how we engage members and activists in this topic around environmental racism," explains Wilson. "However, our goal is to work in partnership with other community organizations who are speaking for broader racialized communities."

INDIGENOUS ACTIVISM INSPIRES

Gairey and Wilson also touch on the connection they see between the struggles of racialized settler communities in Canada and Indigenous communities with respect to climate change and environmental racism. "We're very much inspired by the Idle No More movement and activism among Indigenous peoples who protect the water, protect the earth, protect treaty rights. In our view, that level of activism can help inspire — it does inspire — Black trade unionists to similarly engage in actions, in activism, around environmental racism," explains Wilson.

"The history and the philosophy underlying Indigenous struggles around climate change is so profound within Canada and parallels can be drawn. But we also have to recognize that there are specific historical contexts for the struggle of Indigenous peoples, specifically emanating from treaty rights, as an example. That said, we believe the issue of environmental racism and climate change creates an opening to build connections."

BUILDING SOLIDARITY

According to Wilson and Gairey, that issue provides a foundation upon which they hope to build stronger solidarity between Indigenous and anti-racist movements in Canada. To that end, the project's facilitation questions, case studies, research data, materials and participant groups will all be inclusive of both racialized and Indigenous peoples, says Wilson, so that conclusions drawn and actions developed truly capture the varied lived experiences of those who are dealing with environmental racism. Engaging with other social and political movements, as well as working with labour organizations and activists, is a huge element of the project.

KIDS IN THE WOODS

Wilson is also on the board of the Kids in the Woods Initiative, known as KIWI. Over 2,000 kids have been through the program, which provides outdoor nature experiences for children and youth in Rouge National Urban Park. Commonly known as "Rouge Park," the area is made up of beaches, marshes, farms and Toronto's only campground.

A management plan for the park is currently being completed by the federal government, with a goal of having the final area span nearly 80 square kilometres, through the cities of Toronto, Markham, Pickering and the township of Uxbridge in Southern Ontario.

KIWI activities in Rouge Park are split into two types. The first includes nature games and skills like mapping and tracking. The second is mentoring, by which the organization aims to help kids build a relationship with nature, and with each other, through storytelling and physical challenges.

Its activities are offered through weekday and after-school programs as well as through half-day programs on Saturdays. There are also summer camps and field trips, with the programs accommodating kids from one to 15 years old.

"This organization," says Wilson "is an example of how the Environmental Racism Project can build links to other community organizations that are involved in the environmental justice movement in different ways. That's one way of doing it, and a very subtle way." Wilson believes it's vital to "reconnect kids to nature and build that commitment to valuing our earth. And it's also connected to environmental racism because part of the objective is to ensure that the kids are diverse and reflective of the diversity of our various communities."

With glowing feedback following the first workshop with ETT, the future of the Environmental Racism Project looks promising. According to ETT executive member Joy Lachica, "it was such an amazing workshop. I felt that the passionate hearts for these issues found resources, support and new vision for this work at their sites."

CREATING NEW SPACES

The project's goals going forward are to facilitate more workshops, as well as make all workshop and research materials publicly available. There is still a long road ahead in shifting the systems in Canada that sustain environmental racism. "This is a struggle for a reason," says Gairey. "We're trying to create new spaces in terms of labour education on environmental racism."

Wilson believes it's important to shatter the myth that Canada is a "kinder, gentler, greener nation," leading the way on climate change and racial equality. That's not true," he says. "And we intend to demonstrate that and raise awareness, but ultimately the objective is engaging activists in the struggle."

Haseena Manek is an Ottawa-based labour journalist, and Our Times’ Online Community and Outreach Coordinator. Follow her on Twitter here.