"I can't work if I can't breathe," writes Mark Brown in the Summer 2016 edition of Our Times. Those words are central to Brown's argument that the Canadian labour movement must support the Black Lives Matter movement. His call to action couldn't be any more urgent.

"Mass Incarceration — Modern Day Slavery," a workshop held by the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists (CBTU) at the 2016 World Social Forum in Montreal, trained its lens on an essential part of the struggle Black Lives Matter has taken up: Systemic anti-Black racism is especially entrenched in the criminal justice system.

Black and Indigenous inmates are hyper-overrepresented within the prison population, both in Canada and in the U.S. As noted by the Torontoist's Catherine McIntyre in her article "Canada Has a Black Incarceration Problem", Black inmates are the fastest growing group in Canadian federal prisons — their numbers have increased by 70 per cent within the last 10 years.

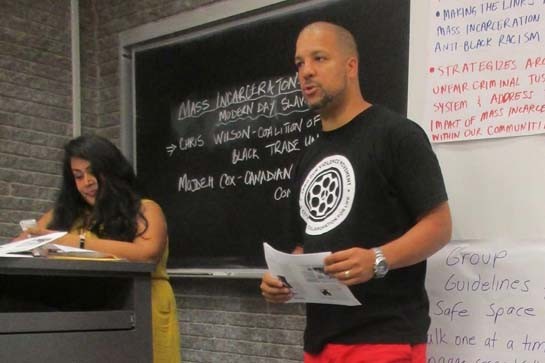

Mojdeh Cox (left) and Christopher Wilson facilitated the workshop. PHOTOGRAPH: CAROL BAKER/OFL COMMON FRONT

LABOUR MUST JOIN THE STRUGGLE

With its workshop, the CBTU built the case that labour must join the struggle to end the mass incarceration of racialized and Indigenous people across North America and throughout the world. We cannot truly combat anti-Black racism without doing so.

Designed by co-facilitators Mojdeh Cox and Christopher Wilson, and organized by Isabelle Miller, the CBTU workshop was modelled upon "Mass Incarceration: A Module of Common Sense Economics." The latter comprises part of a training program originally developed by the American Federation of Labor and Congress on Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO).

Along with integrating a Canadian perspective, the objectives of the CBTU's workshop were to:

- identify the impact of mass incarceration upon racialized communities

- make links between mass incarceration and anti-Black racism

- develop strategies to confront racism within the criminal justice system

- respond to the impact of mass incarceration within our communities

The workshop was open to all World Social Forum participants and included community organizers, trade unionists, prison abolitionists, and other social justice advocates. Beginning with a discussion about what mass incarceration means, participants shared their experiences and knowledge based upon the principles of popular education and then developed the following definition together:

Mass incarceration occurs when there is an over-representation of particular groups, especially racialized and Indigenous peoples, within prisons and other centres of detention. Discriminatory police interactions arising from carding of racialized communities are one cause of the disproportionate rates of imprisonment.

Mass incarceration is further perpetuated on a systemic basis by laws and policies designed to criminalize and warehouse so-called unwanted populations including people struggling with mental health, the poor, migrant workers, racialized and Indigenous peoples.

Mass incarceration is rooted in a racist and colonial history dating back to slavery both in the United States and Canada. Mass incarceration and capitalist exploitation are linked when prisons are privatized, such as in the United States.

For facilitators, predicting the experiences, backgrounds and knowledge of participants was nearly impossible — but that's the beauty of popular education. The workshop was enriched by activists sharing their own stories, with their experiences both setting the tone and revealing the urgency of the crisis.

TELLING STATISTICS

We looked at some telling statistics: In 2016, Canada's crime rate hit a 45-year low. Since peaking in 1991, the crime rate has been cut in half. At the same time, the number of people incarcerated has hit an all-time high.

According to the Maclean's article "Modern Day Residential Schools," the incarceration rate for Indigenous women has increased 112 per cent in the last decade. In federal prisons, Indigenous inmates account for 22.8 per cent of the total incarcerated population, while representing only 4.3 per cent of the total Canadian population.

While the Black population of Canada is three per cent, people of African descent represent 10 per cent of the federal inmate population, notes the Torontoist's Catherine McIntyre. And according to the Toronto Star's article "Unequal justice," Black boys are four times overrepresented versus white boys in youth jail populations, while Indigenous boys are five times overrepresented.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Isabelle Miller, CBTU International Executive Board Member and National Vice-President of TWU USW Local 1944; Dennnis Williams, CBTU Member-at-large, and United Steelworkers Member; Diana Farina Latif, TWU USW Local 1944

Statistics, however, do not give voice to the lived experiences of racialized and Indigenous peoples, so workshop participants also discussed the human side of mass incarceration.

One participant brought attention to the politics behind mass incarceration, saying that certain U.S. states manipulate voting districts to ensure Republicans win. Those elected officials in turn maintain harsh sentences for minor drug offences as part of the "war on drugs." Although whites and Blacks engage in similar levels of drug use, Black youth are disproportionately targeted by policies and policing deployed as part of the "war on drugs."

Interviewed by Catherine McIntyre in the Torontoist, Anthony Morgan, a lawyer and activist formerly with the African Canadian Legal Clinic, notes that it's tempting for many to think of mass incarceration as an American problem. He points out, though, that the overrepresentation of the Black population in prisons is slightly higher in Canada than it is in the U.S.

Morgan goes on to say that part of the problem lies in "the myths we tell ourselves about multiculturalism, and thinking that we have it all figured out. The truth of the matter is, when you look in our prison systems, if you go to our courthouses, if you go to Children's Aid offices, to school detention halls, it is overwhelmingly Black kids who are being criminalized and punished. I think the generalized silence has to do with what we want to believe about ourselves as Canadians."

REAL-LIFE SCENARIOS

Workshop participants reviewed case studies of real-life scenarios, among them the story of a formerly incarcerated African American man who had been convicted of marijuana possession with intent to distribute, following a plea bargain. Jeff, not his real name, sought to find employment and to reintegrate in society but faced mounting barriers as a result of "the box" that employers use to question job applicants on their criminal background.

That the cycle does not end with the prison system itself was reinforced by a participant who noted that, regardless of the nature of the job, some employers in Canada also do criminal background checks and discriminate against candidates with criminal records.

THE NEW "JIM CROW"

Mass incarceration is increasingly being labeled the "new Jim Crow." Michelle Alexander, U.S. author and civil rights lawyer, traces an unbroken line from the Atlantic slave trade, to the institution of slavery, to segregation, to mass incarceration and deliberately discriminatory policies — what Alexander deems "racial control under changing disguise." Her book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, highlights both the scale of the crisis and the deeply rooted nature of it, and illustrates how a new host of discriminatory policies were instituted, not by accident, at just the time civil rights gains were being made.

The workshop concluded with a discussion on the question: What can the labour movement do to help change this unfair criminal justice system and mass incarceration? Participants also brainstormed about individual,community, and political actions they could take after the workshop to address the issue.

Although positions varied, consensus was reached on one crucial point: racism has no place in our movement.

Facilitators handed out a supporting document, a statement from Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) president Hassan Yussuff calling on mayors to address systemic racism in policing. One participant succinctly took issue with Toronto Mayor John Tory, Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson and other apologists for state-sanctioned violence, saying: "We don't want 'em."

"I thought it was a particularly important workshop because CBTU was leading the discussion," said participant Tanya Ferguson, an organizer with Workers United, and a member of Our Times' editorial board. "I'm really interested in figuring out how to expand the labour movement to include these big problems that heavily impact upon our community, but tend to be lower on the list of priorities of organized labour."

Change will not occur because of a single workshop. Ongoing conversations, regardless how difficult, are needed among rank-and-file members to truly engage the labour movement in the Black liberation struggle — and for members to become truly aware of what is really at stake.

As a community organization rooted in the labour movement, CBTU is encouraged by working with the Canadian Labour Congress, and open to working with any affiliated union interested in delivering this workshop to confront anti-Black racism within the criminal justice system.

"We shall not be moved," BLM activists chant. "We believe we can win."

— Our Times Magazine

PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY CBTU

SIDEBAR

WHAT'S THE WORLD SOCIAL FORUM?

Each year, tens of thousands of social justice activists from over 100 countries come together at the World Social Forum (WSF). The shared objective of the forum is "to build a sustainable and inclusive world, where every person and every people has its place and can make its voice heard."

Although the Battle of Seattle protests against the World Trade Organization's Ministerial Conference of 1999 are often seen as the moment that galvanized the anti-globalization movement, it was actually the World Social Forum with its rich history of mobilizing global resistance to neo-liberalism, neo-colonialism and imperialism that was first conceived of in 1996 as an alternative to the yearly World Economic Forum held in Davos, Switzerland.

The World Social Forum grew out of a longstanding tradition of Latin American radical activism and aimed to bring people together from all around the world. First held in Brazil in 2001, the global forum has since been held in India, Mali, Venezuela, Pakistan, Kenya, Senegal, and Tunisia. Montreal marked the first time the WSF was held in North America, with regional social forums taking place across Canada and around the world to link the local to the global. Workers, as well as labour groups, are central to the movement.

Under the 2016 theme "Another World is Necessary, Together It is Possible," spaces were created through assemblies, conferences, self-organized workshops and demonstrations to challenge capitalist exploitation, racism, environmental destruction and all forms of systemic oppression.

Overshadowing the 2016 forum was the Canadian government's denial of visas to many participants from Latin America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East — an especially troubling development, since the WSF is meant to highlight voices from the Global South.

Going forward, many are calling for the forum to be held in countries where international attendees will not be subject to the kind of "institutionalized prejudice and injustice against non-Western peoples" that they experienced from the government in Canada.— CW, MC, IM

If your union is interested in delivering CBTU's workshop, visit their website for more information.

Christopher Wilson and Isabelle Miller are international board members with the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists. Mojdeh Cox is with the Canadian Labour Congress, and is the founder of Women in Colour.