Suzanne MacNeil is a woman at the crossroads of the labour movement's past and future. She's the Nova Scotia Federation of Labour's vice-president for young workers, and also the first female president of the Cape Breton District Labour Council. A casual worker in the registrar's office at her alma mater, Cape Breton University, she says, "It's not really my main gig." Her primary interest is helping the labour movement tune in to the realities faced by younger workers and recent graduates, while revitalizing itself in the process.

MacNeil first connected with the labour movement while she was a student at CBU, editing The Caper Times, the student newspaper, and doing freelance journalism. Working alongside other students, some of whom were aspiring to become full-time journalists, MacNeil observed the sacrifices people were making in order to become employable. "At the time, a lot of us were told that the jobs weren't necessarily here in Cape Breton anymore, like they were a generation ago," says MacNeil. Students keen to start freelancing, in order to start a portable career, found they had to do a lot of unpaid and unrecognized work.

MacNeil saw a similar pattern among her student-newspaper counterparts, right across Canada. The political science major says she noticed a trend toward employers expecting a pool of freelance workers available for "any kind of media work," and she learned, firsthand, how this kind of arrangement can be used against freelancers. "The very first article that I had a byline for under my name, I never got paid for," she recalls with a still-incredulous laugh. "I didn't think too much about it at the time. But, as I became more active, I saw that this was actually a major issue for a lot of folks in the business."

The experience didn't just make her get mad or get even — it made her join a union. The Canadian Freelance Union, to be precise. It is now a community project of UNIFOR, but started out as Local 2040 of the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada.

MAKING UNIONS WORK FOR MILLENNIALS

Although her parents weren't union activists, MacNeil says she was drawn to the role when she was too young to know much about how unions worked. Issues attracted her to the movement: "Not getting paid, or having to sign over more and more rights for less and less remuneration — a lot of those kinds of issues," she says.

After becoming the only Canadian Freelance Union member in her area, the Glace Bay-raised writer wanted to connect with other Cape Bretoners who were active in their unions, and that's how she became involved with the Cape Breton District Labour Council.

"I'd always been politically minded," says MacNeil. "I already knew what unions were, but I didn't really know how they applied to me until I came to understand what their role might be in terms of my writing and how I wanted to earn a living." Still, after becoming active in her union and labour council, she observed that most of her union peers were considerably older than she was, and she felt that this significant age difference was problematic. "The labour movement is running into challenges in terms of getting younger people involved in the struggles that the unions are facing," she tells Our Times from her Sydney workplace. "And there are a couple of reasons for this."

The Nova Scotia Federation of Labour's recently elected VP representing young workers says she is exploring the factors that have led some of her generation to view unions as unsuited to the distinct employment issues of millennials (those born between 1980 and 2000).

"When you're younger and starting a family and working, you don't think of yourself as having much time for unions," says MacNeil. "One of the other things is, a lot of people, when they become a union member, don't go to meetings right off the bat," and don't necessarily know what a union is.

She notes that younger workers appreciate real-life demonstrations of what a union can do, and that rhetoric from movement elders is not enough to win the interest and loyalty of the under-35 demographic. "Oftentimes, for young people, there needs to be that one experience that gets them involved: it might be a strike at work, or that they were in trouble and their union helped them out."

COAL MINES OF CAPE BRETON

In a place like Cape Breton, where unions are still commonly equated with heavy industry and mining, MacNeil's ever-present challenge is to bring present-day workers' situations and concerns to prominence. When people in Cape Breton think of unions, "a lot of them think about the industries we used to have, and of the historic labour struggles that happened around those industries and some of the battles that were won," she notes. "When we lost those industries, I think it wasn't just the loss of the jobs that hurt; it was the loss of our identity, and the ability to see how we might get to a place where we could be prosperous again."

The Sydney Steel Plant Museum website notes that, after over a century of steel production (mainly rails), the plant closed for good in 2000. The Prince Mine, Cape Breton's last operational underground coal mine, shut down the following year, after a failed attempt to procure an American buyer. The Cape Breton coal mining industry dates back to the 1720s. Both industries left an indelible mark on the island and its people.

Union membership in Nova Scotia has largely shifted away from the industrial and natural resources sectors over recent decades. "What happened is the unionization of a lot of the civil service; a lot of public services," says MacNeil. So, even though a coal miner remains the archetype of a Cape Breton worker, frequently invoked in the public's imagination, in 2014, a teacher or nurse or other public sector employee is more representative of a typical Cape Breton union member these days. But the young president of the Cape Breton District Labour Council doesn't view the persistence of historic imagery as a bad thing for the future of the movement.

GOOD JOBS NEVER A GIVEN

"One of the things I love about a place like this is that we have such a sense of our people's heritage," she remarks. "But I think that ever since we lost those industries, it's been a bit of a blow to our collective self-esteem. So, building up what we have now as something that is worth fighting for, and worth protecting, is what I want to do."

MacNeil says she wants to let younger workers know that the regional coal mining and steel industries didn't start out providing "good" jobs. "Good jobs are never handed over on a silver platter by an employer. They become that way because people fight and organize to make them that way."

The Cape Breton labour wars of the 1920s saw thousands of workers rebel against the violent and union-busting tactics of BESCO (the British Empire Steel Corporation). BESCO called upon company police, provincial police and even the military to suppress the uprisings, but the miners, who belonged to the United Mine Workers of America, won out. Davis Day marks the death of William Davis, shot and killed by company police near New Waterford as he and other miners were entering the fourth month of the long 1925 strike. The June 11th memorial day is still dedicated to Davis, and also commemorates all lives lost in the coal industry.

"Right now, what we're facing isn't just about protecting the unionized jobs that we have; it's also about organizing new workplaces," argues MacNeil. She cites the Halifax baristas, who successfully organized two coffee shops in 2013, as "good examples": the workers decided to join Service Employees International Union Local 2 rather than accept stereotypes about what kinds of workplaces can and can't be organized. Changing these perceptions won't happen overnight, notes MacNeil. "We're still figuring out, as a movement, how to make this happen."

One campaign that's attempting to improve and broaden the popularity of unions is the Canadian Labour Congress Together FAIRNESS WORKS campaign, with its message: "The labour movement is not just about decent jobs, it's about a better life, for everyone."

The CLC defines a young worker as someone under age 30, but the Nova Scotia Federation of Labour's definition is someone under age 35, due to the prevalence of an older demographic in MacNeil's home province. She argues that settling on a precise age matters much less than addressing the distinct employment trends currently affecting Canadians in their teens through mid-30s.

A GRANDFATHER'S GOOD ADVICE

"When my mom and dad were entering the workforce, they were in their early 20s, and they weren't just entering the workforce to have a job to support themselves. They were entering it as in: 'Now we're beginning our careers.'" MacNeil's mother worked as a nurse before opting to become a stay-at-home parent, and her father works as an engineer. Such full-time, long-term positions are difficult for millennials to land, especially if they would like to stay in Cape Breton, or Nova Scotia in general. While MacNeil's parents were able to purchase a home in their 20s and attain a stable life by age 30, the 30-year-old activist says "that's not the same story that young folks are able to write for themselves today."

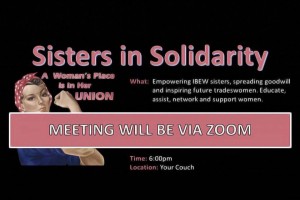

MacNeil remarks that it's not just changing times that motivated her to get involved in the labour movement — it's in her blood. She laughs that her mother jokes about "these things skipping a generation," explaining that her maternal grandfather was Glace Bay coal miner and "union guy" John Bernard Campbell. He was a member of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), and on their executive for a period of time. Winnie Campbell, MacNeil's grandmother on her mother's side, was also political and pro-union. "She was involved in the New Democratic Riding Association, on their executive," says MacNeil. "I believe the riding at the time was Cape Breton East."

MacNeil says that while her grandmother passed away before she was born, her grandfather is now 95 years old and proud of his granddaughter's endeavours. "The one thing he always says to me is, 'You need to get yourself a copy of Robert's Rules of Order. It's the very best thing you can ever do for yourself: know how to run a meeting.' And, you know, it's good advice!"

COLOMBIAN SOLIDARITY INSPIRES

She says her years as a political science student also opened her eyes to the power of solidarity. "I had the opportunity to go to Colombia on a human-rights delegation and then, the next year, to assist with research that a professor at CBU was doing," MacNeil recalls. Visits with Colombian trade unionists were memorable because they expressed interest in international social movements and struggles, even when they knew that their own lives were at risk domestically, just because they belonged to unions.

"At the time that I was visiting, the number of Colombian trade unionists murdered was comparable to the total for the rest of the countries of the world, combined," she adds somberly. "When you're working in a country like that, you depend on international solidarity and the eyes of the world watching, to remain safe in the work that you do."

Back in Cape Breton, the challenges of the past are qualitatively different from the challenges of the present for workers. "Young people can't necessarily stay here and work," MacNeil points out. "They have to go elsewhere, permanently, or go to Fort McMurray, for example, and do weeks, or months, of work there before being able to come home for a while. It's still a pretty difficult arrangement." Another pressing concern is employer and government reliance on the Temporary Foreign Worker Program as a source of inexpensive, readily available labour.

BEYOND US VS. THEM

"Part of it is, when people — white people — see their kid not able to get a job somewhere but they see non-white folks working, they make certain assumptions," she offers. "But I think our movement has been making efforts to educate people on the nature of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program: what exactly it does; why workers come here; what kind of conditions they face. And I think when people have that information, their attitude completely changes."

MacNeil says that anti-racism work and solidarity with foreign workers have been important causes for Canadian labour activists and unions for many years. Still, the need for truly representative leadership in the movement is becoming apparent — MacNeil admits she's often the most diverse member at meetings she attends, on account of her age. "Most of the time when you see labour folks gathered together in Nova Scotia, you see a lot of white faces. Old white faces," she says, not without an affectionate touch of humour in her voice.

The Sydney resident is critical of the Conservative government's austerity-style spending and how it's shaping the future of employment in Canada. "Everything has been about the individual, and messages about 'what you choose to do with your life.' It gives young people the impression they have more choices than ever before, but, actually, we have fewer supports than before to make any of our goals a reality," notes MacNeil. "We're on our own in a way a generation hasn't been in a long time." Yet, at the same time, she sees recent events driving workers and community members closer together, bound by collective outrage at events like the closure of the local Veterans Affairs office in Sydney at the end of January.

"The recent rally in Sydney against the closure of the Veterans Affairs offices was spearheaded by the Union of Veterans' Affairs Employees, which represents the workers there, and it was supported by the veterans they serve on a daily basis," says MacNeil. "What was really notable about that particular rally, and the organizing effort behind it, was that the community came together in a way that a lot of people hadn't seen in a long time."

She says Cape Bretoners were also very active at a series of town hall meetings about cuts to Employment Insurance eligibility for seasonal workers. Hosted by labour councils and the Nova Scotia Federation of Labour, they garnered significant interest. "The one in Cape Breton was the biggest. We had about 300 people in attendance and probably twice that watching the livestream!"

MacNeil is a realist and a socialist. She dreams of a day when more people can live and work in Cape Breton, in environmentally sound, unionized industries. She wants to sustain the momentum of the Veterans Affairs rallies, even as she sees workers being hit by "attacks on all fronts." The end of door-to-door mail delivery by Canada Post letter carriers and looming threats to the Canada Health Accords are just the tip of the iceberg: "Just about everything that's coming down on the federal level is negatively impacting us in some way."

Rather than passively awaiting the next federal election, or strategizing personal career moves in the free-market economy, MacNeil's peers are being encouraged by the union activist to dream big, and to work with union locals at the labour council level. "I do have hope and optimism," MacNeil smiles. "But the price of hope and optimism is a lot of work and organizing."

Melissa Keith is a former radio broadcaster and an award-winning freelance journalist. She lives in Lower Sackville, Nova Scotia.