Has Naomi Klein ever seemed so prescient? In her 2007 classic, The Shock Doctrine, Klein lays out how neoliberal governments consolidate power and expand private interests, centring her argument on economist Milton Friedman’s observation that "Only a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change. When the crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.”

Disaster capitalism

Klein’s book produced the term disaster capitalism as shorthand for describing a host of practices and policies deployed by conservative governments in Canada, the U.S., and beyond, to weaken the social safety net, expand privatization in nearly every public service, and intentionally distance people from one another through entrenched income inequality and the erosion of workers’ rights — all under the guise of crisis response.

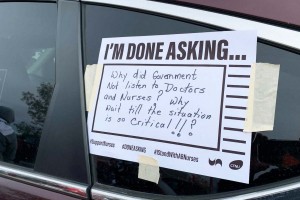

PHOTOGRAPH: LORRAINE ENDICOTT/OUR TIMES

That said, there has been a corresponding rise in organizing — from Indigenous rights to migrant workers’ rights to $15 and Fairness campaigns to climate justice — that is rooted in people, equity, and meaningful connection.

Organizing for the common good

Largely successful fights to protect public education have grown across North America, with elementary and high-school education workers leading the revolution by arguing for meaningful investment in all students and education workers, while college and university faculty have organized around equity and job security for contract faculty. Both groups have directly connected their fights to improve and protect quality education to larger social issues: this is whole-worker and whole-student organizing for the common good.

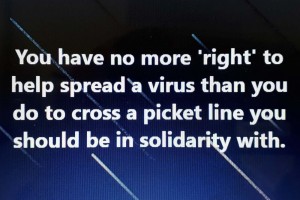

What we are seeing now in Canada in response to the coronavirus pandemic exemplifies the tension between these poles: think of it as disaster capitalism vs. disaster socialism. On the one hand, we have the federal and provincial governments employing messaging that targets the “public good” as well as workers and families. All the while, they are actively poised to support and protect businesses and industries, but are falling short when it comes to doing the same for people and workers.

They are also moving to celebrate private corporate interests as best situated to provide the services we will need to save the economy. In the meantime, they are preparing to trample, or are already trampling, collective agreements and Charter rights, while propping up polluting industries (think oil and gas, airlines, and cruise ships), landlords, and the stock market.

PHOTOGRAPH: LORRAINE ENDICOTT/OUR TIMES

On the other hand, “caremongering” groups are popping up in neighbourhoods and workplaces to provide support to those who need it — offering to make, deliver or pick up food, run errands and get medication, and provide other services. Advocacy groups are calling for rent relief, access to health care and enough income for all.

Most heartening is that the left is beginning to reap the benefits of decades of organizing around anti-poverty, migrant, and workers’ rights, and that the conditions we all face in the pandemic have brought these issues into sharp relief for many more of us. People care, and are starting to see that care must be a fundamental organizing principle in our economy. (This is beautiful.)

Shift to a better world

The excuse that there is not enough money to fund decent work, quality health care, schools and education, social housing, and a fair minimum wage is being proven false. It’s now clear that governments can direct resources to meet their priorities. For the moment, public health is the priority, but what’s also become clear is that ensuring any semblance of economic stability long-term means supporting workers now. The question facing us is how we expand these protections to ensure no one is left out, and to use this knowledge and momentum to shift permanently to a better world.

PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY JP HORNICK

I am a worker in the Ontario college system, and a parent to a kid in Grade 5. From where I sit, these two public education systems are an excellent example of where we face these tensions, and where we can truly shape the future. As college administrators scramble to finish this semester and adapt for the next, key issues have come to the fore.

Top-down online learning models

College administrators are attempting to move curriculum material online largely without faculty input, using a top-down model that may not work for all program areas. For example, faculty teaching in the trades or in nursing need to be intimately involved in discussions about how to best address practical learning in labs during these days of social distancing. Intellectual property protections need to be in place so that faculty can share teaching loads and work in order to make up for the inevitable increase in professors off work due to quarantine or caregiving responsibilities.

Currently, faculty are at risk of having their materials used without their knowledge or consent. Contract faculty will play even more crucial roles in the development and delivery of curriculum, but will need better job security and guaranteed hours to provide seamlessness and stability for students.

For the current semester, all teaching faculty are working on a just-get-it-done model so students can finish their year and demonstrate that they’ve met the vast majority of required course outcomes. That means we must now, and possibly during the fall semester, rely increasingly on online courses. Those courses, though, should be developed by faculty who were actively teaching in classrooms before the pandemic shut down schools: They are experts in their fields, but they also know what students need to know and how students best learn that material.

Some colleges, however, are looking toward publishers and private curriculum-development companies as a quick fix to provide standardized curriculum — companies that are also likely to provide kickbacks to those colleges using their material.

PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY ETFO

The over-reliance on recruiting international students to make up for years of government funding shortfalls now means that $1.15 billion dollars in Ontario college tuition is also at risk, particularly as travel restrictions are imposed, restrictions that will likely remain in place for some time.

To maintain international-student enrolment levels (which at some colleges account for more than 50 per cent of all student enrolment), the pressure will increase to provide low-cost online learning that can be accessed from anywhere. The temptation to rely on prefab curriculum will be strong.

Relying on private companies may seem like an easy, short-term solution to providing new curriculum and addressing funding shortages, but it doesn’t address the larger issues that will arise down the road when the standardized content becomes increasingly disconnected and irrelevant, and a professor is reduced to little more than a replaceable curriculum delivery agent. The erosion of both quality education, and quality employment both within and outside the education sector, will accelerate dramatically.

Faculty and students must be included

These scenarios alone have grave implications for employment equity, shared governance and intellectual property concerns — all key issues in the most recent round of faculty contract bargaining. What’s clear is that college faculty are crucial to the ongoing quality and stability of the Ontario college system.

To meet the challenges of the changing post-secondary landscape, the voices and ideas of faculty and students must be included in any restructuring. Free tuition, student-loan forgiveness, and adequate government funding are essential to rebuild our economy and to support students. Students and faculty are current and future workers after all, and their labour and wages will be the foundation that supports any possible rebound.

In mid-March, the Ontario government posted its initial list of resources to help parents support their kids’ learning while schools are closed, and nearly simultaneously announced settlements with two of the teachers’ unions engaged in provincewide strike actions. Setting aside the fact that the provincial lists were woefully incomplete, they also demonstrated a set of assumptions around access to the internet and supporting technologies that fundamentally disadvantage marginalized students.

The Ford government’s plan of initially relying on TVO (TV Ontario) and a list of links to existing online resources forwarded the premier’s already explicit agenda of forcing curriculum online and paved the way directly for private interests to become major players, while sidelining teachers themselves. As the rollout of online learning during the pandemic continues, all signs point to Stephen Lecce, Ontario’s Minister of Education, eventually using this to undermine the professional expertise of K-12 teachers (“see, it’s easy, anyone with a computer can do it”) and rolling back gains made around special-education supports and diverse classrooms.

Good, responsive curriculum can be developed only by teachers who are engaged daily with the complex needs of their students. Truly understanding a student means engaging with the whole student. Many, for example, live in communities and families that are changing or in flux, and many have needs that are often at odds with streamlined content and its pre-determined timelines for learning.

We have a chance to avoid mistakes

In Ontario, we have the chance now to avoid the worst mistakes made by the U.S .and Australia, where charter schools and standardized curricula have fueled two-tiered education systems based primarily on income. And if there was ever a case to be made for making telecommunications a public utility, access to education in a time of pandemics is it.

What faces us is a challenge to organize students, teachers, and parents around the notion that fully funded, equitable, and accessible public education is a part of the foundation upon which the collective good rests — not just from K-12, but through post-secondary, and to expand this notion to include all public services.

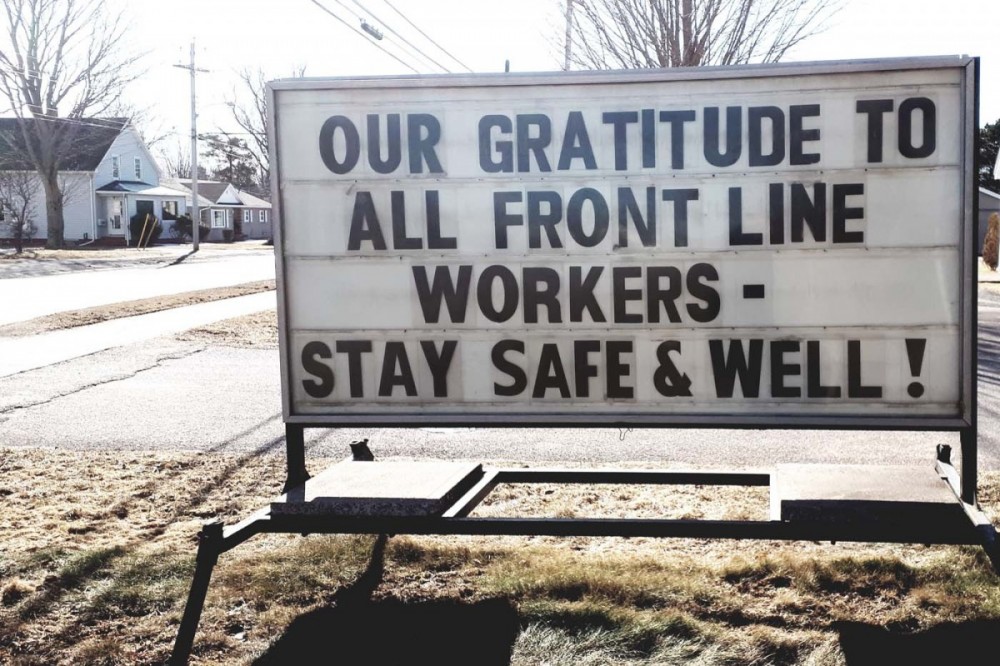

PHOTOGRAPH: LORRAINE ENDICOTT/OUR TIMES

We must resist the falsehood that innovation through privatization is the only way through this pandemic or any other emerging crisis. While there might be some initial benefits in terms of speed, the larger and long-term social costs are too high a price to pay. Right now, the value of all workers — from the superheroes stocking grocery-store shelves, to the health care workers giving their all on the frontlines of the pandemic, to the postal workers keeping communications flowing — along with the brilliance of shared and funded public services are undeniably visible.

We are all truly in this together, and we cannot in any way go it alone. This pandemic is a blow to the crass individualism fostered under neoliberal capitalism. For us to survive it, literally, collectivity and connection must triumph over profit and personal gain.

This isn’t the last time we will face a challenge like COVID-19; we are likely at the start of our new normal of cyclical pandemics. The seeds of an entirely different kind of social and economic organizing are “lying around,” right in front of us. We just need to organize together until the politically impossible, as Friedman said with entirely different intentions, becomes politically inevitable.

JP Hornick is the coordinator of the School of Labour at George Brown College, in Toronto, a long-time social activist, and chief steward for Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU) Local 556.

If you like what you're reading and want to subscribe, please go here. Thank you!