Please note: This piece includes details that readers may find deeply disturbing. The Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line (1-866-925-4419) is available 24 hours a day for anyone experiencing pain or distress as a result of their residential school experience or that of their family.

I’m going to talk about some depravity here but I don’t want you to avert your eyes from these words. This is the truth. And you cannot have reconciliation without the truth first.

I have been a union member for my entire adult life. Sometimes I have given more than I should have to this movement — this powerful movement that I love so dearly. And so, even though this is probably the most difficult thing I have ever written, I do so because it is necessary to speak the truth, even if your voice shakes.

On June 2nd of 2021, non-Indigenous Canada woke up to some news that shook it to its core. It woke to the news that on the grounds of schools there were cemeteries. I need you to take a minute — take a minute and picture the school nearest your home. Is there a cemetery at that school? Probably not. It would be unthinkable that there would be a cemetery at a school. And not only are there cemeteries with markers and headstones, but there are also graves full of the bodies of children who were killed in those institutions. That alone is a terrifying picture in anyone’s mind. Then imagine all of the steps that led to there being a cemetery on the grounds of at least 139* “schools” in this country that First Nations, Métis and Inuit children were forced to attend.

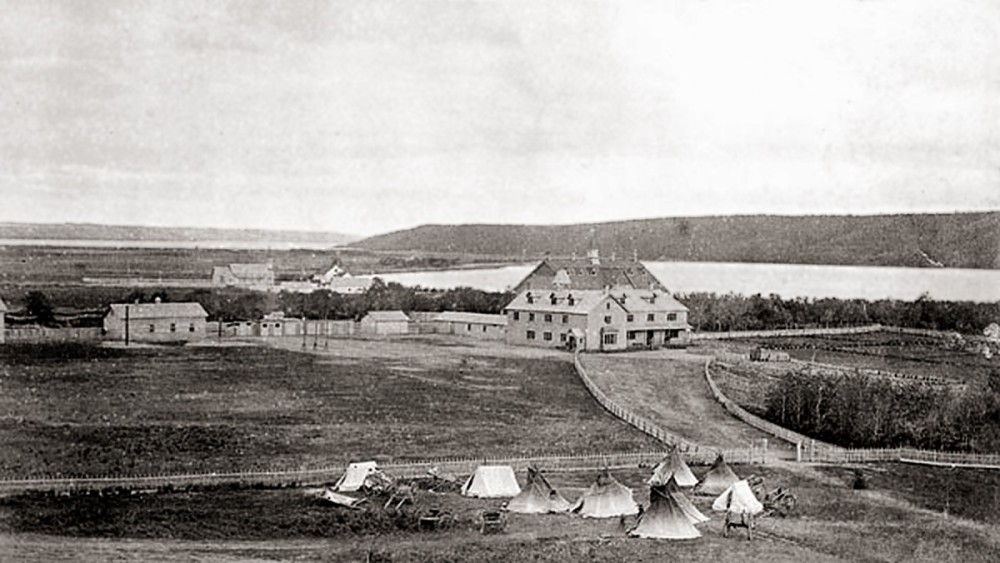

Fort Qu’Appelle Indian Industrial School. PHOTOGRAPH: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS.

The steps are mind-blowing to the average Canadian. They are in fact unfathomable. Yet they happened. Laws were enacted making it illegal to keep children safe and out of those “schools.” And those laws were enforced by Canadian workers, sometimes at gunpoint. Some of those workers were members of unions.

In Canada, the Indian Residential School, the Indian Day School, the Indian Hospital system and the Sixties Scoop are known as a great stain on our collective conscience. They are four systems that, until fairly recently, were not talked about at all and if they were discussed it was likely within the confines of the families of those who had to endure their horrors, or in circles of Survivors.

One place it is guaranteed they were discussed is in the halls of government, in the House of Commons, and in the Senate. Politicians and others convened meetings, wrote letters, made speeches, planned, funded and publicly schemed about all the ways they could destroy Indigenous cultures by destroying family units. And they would stop at nothing to achieve that goal. The architects of these systems are men that, to this day, are revered members of Canadian society — learned about and celebrated in schools that are, in many cases, named after them.

In May and June of 2021, we received loud, firm confirmation of what Elders had been telling us for years — that there were children beneath the grounds of every one of these houses of horror that the government had built to confine Indigenous children and adults. In 2021, organizations of every size and political orientation felt the need to comment. We read and heard expressions of grief and shock and even surprise. Some organizations made gestures of reconciliation as well.

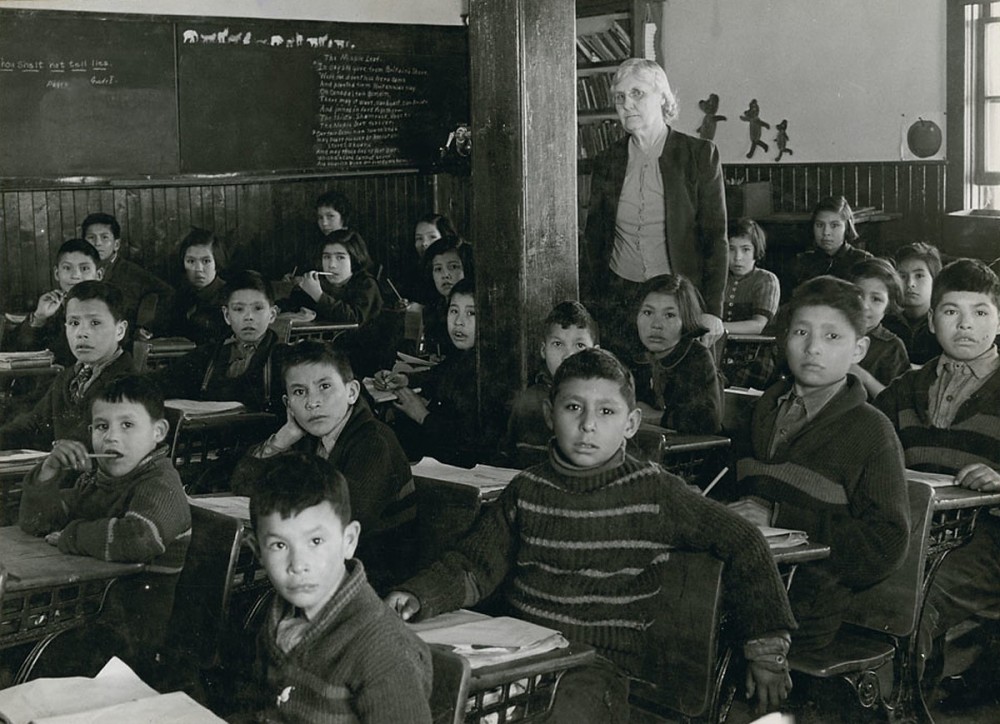

Cree students and teacher in class at All Saints Indian Residential School, (Anglican Mission School), Lac La Ronge, Saskatchewan, March 1945. PHOTOGRAPH: Bud Glunz. Library and Archives Canada, PA-134110.

There are some organizations that have apologized for their role in the creation and upholding of these institutions, but there is one group that hasn’t — at least not that I have heard. Unions. Unions have not only not apologized for their role — both direct and indirect — in the attempts to wipe out an entire group of people, they have barely acknowledged their role in a state-sponsored genocide.

The movement that we all belong to, the labour movement, offered kind and generous words and swiftly admonished the government for not doing more. They scolded the government for being too slow to implement the 94 Calls to Action or the 231 Calls for Justice. They demanded an end to boil water advisories on some 60 First Nations and they implored the government to end their appeals of court decisions. They created orange logos, featured Indigenous art; they encouraged members to share orange squares and wear orange t-shirts. They did what unions are good at — they made noise.

These are all important gestures of solidarity that we have come to expect from unions and union leaders. It’s easy to point to someone else and assign responsibility and culpability. What is much more difficult, and far more rare, is for us to look inward.

I’m going to say it plainly. Union members were involved in the building, the maintenance and the horrors that took place in Indian Residential Schools, Indian Day Schools and Indian Hospitals in Canada from 1828 to 2000. And they were and still are participants in the Sixties Scoop, the present-day child “welfare” system and birth alerts. Unions are still participants (albeit involuntary ones) in the destruction of First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples and their lives.

In my work as a labour educator, I have learned that truth comes in many forms and from many places. This case is no different. Many years ago, I saw a photo that we have likely all seen from the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. It was a picture of Black children and young people being assaulted with water from fire hoses. It’s 1963 and water is pounding on their little bodies as they are thrown around like rag dolls from the force of it, and they are holding on to the trees for dear life. We’ve all seen those pictures but this particular day I saw a picture with a firefighter in the foreground holding that water hose. I don’t know why it never occurred to me that it would be a firefighter holding that hose. Of course it would be. But seeing that man in his firefighting gear with the letters “BFD,” for Birmingham Fire Department, emblazoned on his back stopped me in my tracks. He was a city worker, a firefighter, a union member.

A few months ago, I saw a picture of a train carrying Canadians to the interior of British Columbia to be interned because they were ethnically Japanese. The train had the words Canadian Pacific emblazoned on the side. Why had it never occurred to me that those railway workers were members of the union that I belonged to? And what role, responsibility or benefit had my union incurred as a result?

Ever since that day I have been thinking about the role that union members as workers have played in the oppression of IBPOC people in our society; and the impact that that has had on unions. Equally, and maybe even more, important is understanding how unions have benefited from that oppression. I’m going to bet all the money in my wallet right now that those firefighters were paid overtime to be in that park on that day to commit those acts of brutality against Black children fighting for freedom.

There were 139 Indian Residential Schools listed in the Truth and Reconciliation report released in 2015. The last of these institutions, Grollier Hall, closed in 1997. It was located in Inuvik and run by the government of the Northwest Territories from 1970 on. During the 38 years it was open at least six children died there. One child died as recently as 1993.

There were at least 699 Indian Day Schools throughout Canada from 1863 until the last one closed in Kanesatake, Quebec, on September 1st, 2000. If you’re reading this, I’m pretty confident that you were alive when institutions that purported to be schools and had graveyards on their grounds were open in this country.

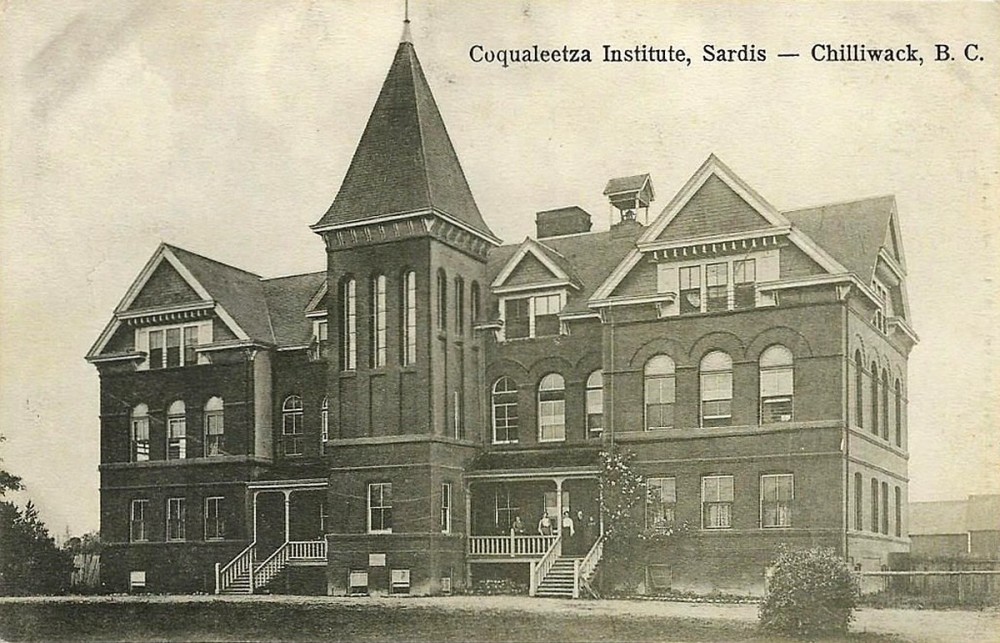

Coqualeetza Industrial Institute. PHOTOGRAPH: United Church Of Canada Archives, Indian Residential School History & Dialogue Centre, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

There were at least 29 Indian Hospitals in this country. The actual number is difficult to pinpoint. What is known is that they were segregated federally run institutions that, under the guise of treating people for tuberculosis, conducted experiments of various types on Indigenous adults and children without their knowledge. What is also known is that patients were often there involuntarily and spent years separated from their families. Many parents, children, sisters, brothers never found each other again.

Operating and maintaining over 850 separate institutions throughout the country is an enormous undertaking. This system, which includes present-day Indigenous child “welfare,” has likely involved tens of thousands of staff over the 194 years of its existence. Again, when we look to the records of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reports or other government archives there is little information on staff to be found.

The Sixties Scoop was a depraved system where children were kidnapped from their parents and given or sold to other families that were deemed more suitable for them. The children were advertised in newspapers across this country.

The number of staff who worked at Residential and Day Schools including principals, teachers, maintenance workers, groundskeepers, cooks, nurses, administration staff, physical education staff, drivers, is unknown. There are rare instances in the volumes of reports of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission where employees are named, but very few are named after the federal government took over control of the schools. There are scant numbers of records of those who abused children and what happened to them. This is either a deliberate omission or a simple product of an extensive bureaucracy.

Based on a 2016 report from the CBC we know that thousands of people who worked in or attended Indian Residential Schools abused children. It is a fair assumption that more than a few of the workers were union members.

One shocking 2016 CBC report notes that, beginning in 2005, as part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement agreement, 17 private investigations firms contracted by the federal government located 5,315 alleged abusers. Of these, 4,450 have declined to participate. Fewer than 50 people total have been convicted.

The same report goes on to say that “The alleged perpetrators, however, weren't tracked down to face criminal charges — it was to see if they would be willing to participate in hearings to determine compensation for residential school survivors. The Independent Assessment Process (IAP), not involving the courts, was set up to resolve the most severe abuse claims.”

I’m also not simply talking about workers who worked in and administered the institutions themselves I’m talking about the ones who flew the planes, drove the trucks, operated the trains that took kids away from their parents and delivered them directly to these houses of horror. I’m talking about nurses who injected children with unknown drugs as research guinea pigs, and orderlies who put casts on the unbroken legs of children to keep them still while doctors conducted experiments on them. I’m talking about the worker who picks up the phone to call in a birth alert – beginning the process of kidnapping newborns from their mother. I’m talking about workers who mailed the bodies of dead children back to unsuspecting parents. I’m talking about the skilled trades workers who built and installed an electric chair in a children’s school.

Dr. Percy E. Moore joined the Indian Affairs Branch of the Department of Mines and Resources in the 1930s. He went on to become director of the Indian and Northern Health service programs of the federal Department of Health and Welfare in 1946 until he retired in 1965. Moore was possibly a union member early in his career. He, along with Dr. Frederick Tisdall and Dr. Lionel Pett, led the operations that conducted “nutrition” and medical experiments on First Nations, Inuit and Métis children in the 1940s and 1950s. Some of these experiments took place at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Until being called out publicly by researchers and students at George Brown College in 2018, the Hospital for Sick Children was celebrating Tisdall’s work on its website and calling him the “father of our childhood nutrition program.”

Moore has a federal hospital (that serves an Indigenous community) named for him in Manitoba.

Tisdall was the President of the Canadian Paediatric Society. Pett has various scholarships awarded in his name by a number of universities across the country. Two were awarded as recently as April 2020.

It should be noted that these experiments led to the creation of the BCG vaccine that is still used to prevent tuberculosis. The “nutrition” experiments led to the creation of Pablum at Sick Kids Hospital. If you don’t know, ask your parents what Pablum is. I mean it — ask your parents. The Hospital for Sick Children continued to receive royalties from the makers of Pablum for 25 years.

The company that made Pablum in Belleville was unionized by my union.

And before you start saying to yourself “there’s no way,” “it’s not possible,” “our union couldn’t possibly have represented workers in those institutions” — I would ask you — have you checked? Have you really checked?

Chances are, no one in your union has checked. Someone should check.

My own union is full of railway, airline and healthcare workers. I would want to know that history.

Unions that represent workers in provincial and territorial and federal governments. Unions that represent healthcare workers, various medical, teaching and other professional associations had members who worked in these institutions and kept these systems going. This means that the torture of First Nations, Inuit and Métis people in this country also kept the unions going.

I will choose to believe that unions were unwitting participants in these systems, but I have questions. They often keep me up at night.

Who were the doctors, nurses, technicians, administrators, pharmacists involved in all of these programs?

Who were the drivers, pilots, ship captains and crews who operated the vessels that transported children hundreds or thousands of kilometers away from their parents?

How much did they charge the government for those services? Or were they union members who were employed by organizations that benefitted?

How many people who worked on those programs were union members? This question must also be asked of medical and educational licensing bodies.

How much money in union dues did unions collect from those members? What have we been able to build with that money?

How many times did unions defend members who brutalized children?

How many times did unions defend members who carried out policies that they knew were wrong?

Did unions attempt to negotiate protections for those who brutalized children?

Did they make “arrangements” to quietly move workers around after they had transgressed?

Did union reps encourage their members to blow the whistle about these atrocities until they had no breath left?

Did unions stop people from blowing the whistle?

Every president of every union and association (especially medical associations) in this country should be gathering their staff together and beginning the process of digging. Look in the archives, scour the documents, dig up the collective agreements, ask more questions, find the truth.

Unfortunately, the labour movement is not removed from these tragic circumstances. The dues that these members paid have contributed to the building of our unions and our movement. What Indigenous people have endured in this country is shameful and, in many cases, criminal. Unions have benefited from this. It is an awful truth, but it must be said.

I do hear the occasional reference to the importance of Reconciliation within our circles. This is encouraging but it feels fleeting. Brief land acknowledgements are not nearly sufficient. They must always be accompanied by action, and actions.

So, what’s next? I hear a lot of talk about decolonizing unions. I don’t see a lot of concrete action. At the very least we must ask some questions. Was the union that you belong to complicit? Did the union you belong to benefit?

In 2021 we commemorated the first-ever National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. I have to say, I didn’t see too many major public announcements from Unions during that time on their Reconciliation plans, and I’ll forgive that year’s out-in-public invisibility — because COVID. But this means that, by now, you have had a year, 365 days, to make a plan.

Start by:

- studying the 94 Calls to Action and 231 Calls for Justice and find ways to put them into practice;

- supporting organizations that are supporting Survivors;

- supporting artistic endeavours by Indigenous artists (without requiring a sponsorship credit).

Use the collective bargaining power we have built up to negotiate things that specifically benefit First Nations, Métis and Inuit members (I guarantee that in the long run the entire membership will benefit).

Use the political power of the labour movement to raise issues.

Support organizations working to preserve the evidence of Indian Residential Schools, Indian Day Schools and Indian Hospitals.

Invite Survivors and their families to tell their stories to your members.

There is no doubt. From here on in, First Nations, Métis and Inuit people are no longer going to remain silent about what they lived through. And the family members of those who lived through horrors but did not come home alive will not rest until justice is served and their loved ones come home to their final resting place. Unions can either be with those families or they can be against them. But they can’t be silent. Silence gives aid and comfort to the oppressor.

A few months ago, in an article I wrote for Our Times, I said, “unions must get serious about racial justice and reconciliation.” Comrades, this is as serious as it gets.

*The TRC was tasked with investigating only 139 Indian Residential Schools. These were federally run. There were others – provincially, territorially or privately run. We don’t know much about them.

Denise Hampden has been a member of Unifor for over 30 years. With ancestors in the soil of Africville and Sipekne’katik First Nation, their legacies guide her work for social and racial justice.

She has spent her entire working life as a labour educator advocating for workers, fighting for justice and dismantling predatory capitalism. Her work is guided by the principles of anti-bigotry, anti-colonialist, pro-feminist, and climate justice work that she has been doing in her union and community.