The first half of 2020 turned most people’s lives upside down. The spread of COVID-19 around the world has disrupted many things: the economy, industries, work, and family life. Nothing is normal. Everyone feels some sort of loss – of income, movement, contact. These are all things that we know will come back in some form as the country moves forward.

But there are some losses that people won’t easily recover from.

To date, over 8,700 people across the country have died due to COVID-19. Despite the early deaths in British Columbia, most of the deaths have been in long-term care residences in Ontario and Quebec. The numbers are staggering, almost unbelievable, except to those who have long known that seniors’ care has been neglected again and again by governments at every level.

Long-term care workers, unions, and seniors’ advocates have flagged the problems existing in this sector for decades. There have been exposés in the media. Health authorities have been told, governments have been told, and despite the overwhelming risk workers face each time they speak up, for-profit owners have been told.

In Ontario, it’s taken a report from the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), who in May were sent to assist in five long-term care homes, to spark public outrage and force governments to pay attention. The problems go beyond just the COVID-19 crisis. Inadequate staffing levels, lack of full-time hours, low pay, inadequate training, lack of medical supplies, the high ratio of residents to staff — these are all well known issues in the long-term care sector.

Why then are so many people and politicians asking themselves only now, “how did we get here?”

Medicare: The Vision

In poll after poll, Canadians pick health care as a top priority. During election time, it’s one issue that all politicians talk about. They pledge to invest more or to make the system more responsive. Then there are those who talk about cutting services.

Most Canadians feel that our system of medicare represents all that is good about our country: When you’re sick or injured, you can be cared for without having to first put down your credit card. Our American cousins remind us every day of how fortunate we are to live in a country where investments are collectively made for the sake of our health.

Medicare has come to mean being insured for care in a hospital or by a doctor. But that’s not what the original vision was. The origins of our health care system are rooted in Saskatchewan, with Tommy Douglas, and he saw something quite different.

As leader of the Saskatchewan Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), Douglas led the party to victory in 1944. Under the CCF, several pieces of important legislation benefitting the common good were passed in the province: public sector workers were given the right to unionize, a number of public crown corporations were created, and a program to give people free hospital care was enacted.

Medicare was Douglas’ preoccupation. He introduced medical-insurance reform in his first term and, by the end of his last term, when he left to run for the leadership of the CCF’s successor party, the New Democratic Party, universal medicine was well on its way to becoming a reality in Saskatchewan. Canadians in the rest of the country had to wait until 1966 when Prime Minister Lester Pearson created the federal medicare program.

But I fear we have lost Douglas’ original vision of a universal health care program.

In 1984, Douglas gave a speech and reminded people, “Let’s not forget that the ultimate goal of medicare must be to keep people well rather than just patching them up when they get sick. That means clinics. That means making the hospitals available for active treatment cases only, getting chronic patients out into nursing homes, carrying on home nursing programs that are much more effective, making annual checkups and immunization available to everyone. It means expanding and improving medicare by providing pharmacare and denticare programs. It means promoting physical fitness through sports and other activities.”

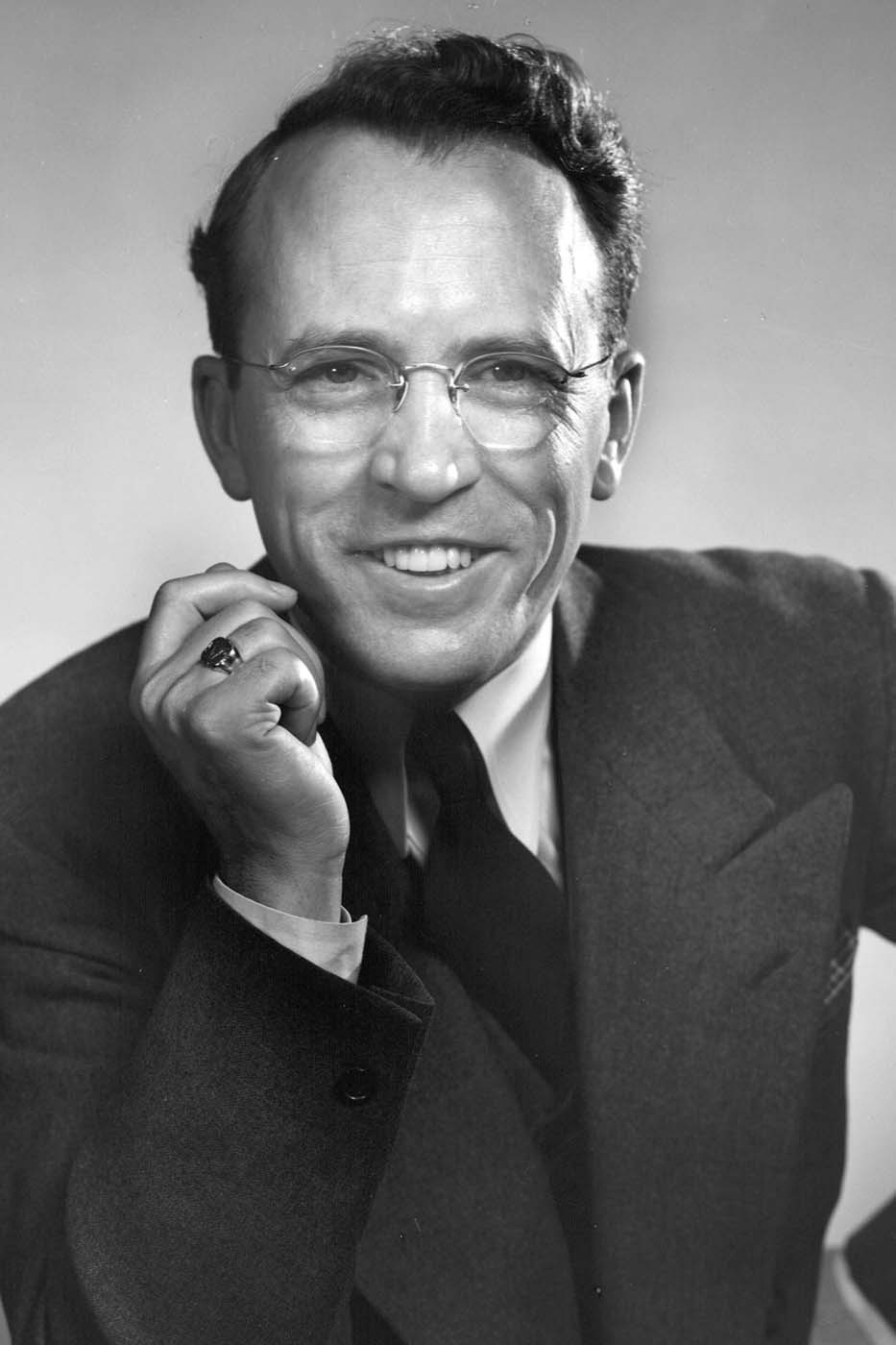

PHOTOGRAPH OF TOMMY DOUGLAS: COURTESY DOUGLAS-COLDWELL FOUNDATION

This holistic vision of what our health care system was meant to be hasn’t come to fruition. A federal government website asserts that the Canada Health Act’s primary objective is “to protect, promote and restore the physical and mental well-being of residents of Canada and to facilitate reasonable access to health services without financial or other barriers.”

Despite this comprehensive-sounding description, many of the things Douglas thought should be included are not. Home care, prescription drugs, and dental care are some of the services that have been left out of the Canada Health Act (CHA). Deemed not medically necessary, these services do not have to adhere to the conditions of the CHA: public administration, portability, accessibility, comprehensiveness, and universality. Nor are there any national standards that must be met before service providers receive public funding.

These exclusions have cost Canadians dearly.

Enter For-Profit Care

In Canada, long-term care has a “mixed-model” system: the sector operates with a combination of government funding and private funding, the latter in the form of private insurance or personal savings.

While the federal government provides funding support to the provinces for sectors like health care, education, and income assistance, the provincial governments determine how much money goes to what services.

Over the years, the federal and provincial governments have severely cut public funding in order to fund other priorities, among them major tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy. While the population of seniors grows, the number of beds in public long-term care homes is not keeping pace. Inadequate spending has opened the door wide to allow for-profit investors to fill the overwhelming need.

According to the Canadian Health Coalition (CHC), a national organization advocating for universal health care, 44 per cent of long-term care homes in the country are for-profit, but the rates differ depending on the province. In Ontario, the rate is between 60 per cent and 70 per cent. In BC, 62 per cent of homes are owned by for-profit businesses or non-profit organizations.

Non-profit homes are generally facilities owned and operated by non-governmental organizations, such as religious and community groups or agencies. Non-profit societies are formed to manage and deliver services. The expectation is that any extra revenue or cost savings will go back into the budget for care of residents, instead of into the pockets of shareholders.

But, in the 2016 paper, Observational Evidence of For-Profit Delivery and Inferior Nursing Home Care: When is There Enough Evidence for Policy Change?, the authors point out that, “in predominantly for-profit environments, some not-for-profit groups, despite their mandate, operate more as competitive market entities, with the focus often shifting towards increasing revenues at the expense of quality.”

This can happen when, for example, non-profit societies contract out the operation of residences to private companies to run as a business. Over the last few months, attention focused on several of these residences due to the number of deaths attributed to COVID-19. The Ina Grafton Gage home in Scarborough is a non-profit home managed by a subsidiary of Responsive Group Inc., a private company. Media reports indicate that 21 residents have died from COVID-19, while 40 others have been infected, in addition to 25 staff members. At the Villa Colombo Senior Centre (Vaughan), managed by Universal Care Canada Inc., 11 residents died. At the Harold and Grace Baker Centre, managed by Revera, at least 13 residents died.

Profit Compromises Care

It’s not just anecdotal evidence: research backs up the contention that profit compromises care. The 2016 study’s authors reveal that “where comparisons of quality have subdivided non-profit ownership into governmental (publicly owned) and non-profit groups, there is often a hierarchy of outcomes, whereby public models are superior to both for-profit and non-profit models and for-profit models are inferior to public and non-profit owned organizations.”

So, no matter how you couch it, for-profit ownership means the same thing no matter where you live. And it’s something all Canadians should be concerned about.

As the Office of the Seniors Advocate in BC pointed out in its 2020 report, A Billion Reasons to Care: A Funding Review of Contracted Long-Term Care in B.C. “for-profit care homes, by the nature of their business, expect to demonstrate a profit/surplus; this underlying fact sets in motion incentives that may, at times, conflict with the best interest of the resident.”

To make money from a long-term care home, its owners need to spend as little as possible, so staff are paid poorly and many workers are given only part-time hours. Positions come with few or no benefits. The central imperative to control costs adversely affects crucial supplies, like wipes and gloves, needed if the home is to operate safely. Corners must be cut somewhere to ensure profit. When that happens, the quality of care suffers — research again backs this up.

In that same study, researchers also reported that “all nursing homes must balance their revenues and expenses to survive. For-profit organizations operate on the principle that profits or net income (revenue in excess of expenses) is directed to the owners, investors, and shareholders. In non-profit organizations and publicly owned facilities, net income is used to benefit clients.”

The paper goes on say that “in order to generate profits, for-profit homes tend to have lower staff-to-patient ratios than non-profit facilities. Money delivered to shareholders and investors leaves less money to pay for staff, and in turn, having fewer or untrained staff is associated with lower quality.”

But what does for-profit care really look like?

An example from the report by the BC Office of the Seniors Advocate noted that the province’s for-profit long-term-care businesses collectively “failed to deliver 207,000 hours of funded care…and to put that into context this means, while the shortfall of 207,000 hours in the for-profit care homes represents only 2% of their funded hours, these hours would be enough to fully staff a 168-bed care home at 3.36 hours of direct care per resident, per day for one year.”

The report also found that “the for-profit sector spends an average of $17 less per worked hour; and wages paid to care aide staff in the for-profit sector can be as much as 28% below the industry standard.”

Low Wages in Long-Term Care

Low wages are a major concern in long-term care. Being poorly paid forces workers to take multiple jobs to care for themselves and their families, and it creates higher staff turnover, which in turn affects the quality and continuity of care that residents receive. During the pandemic, having workers moving between different long-term care homes created an open door for the virus. The B.C. government understood this and quickly restricted people to working at a single site. At the same time, wages were increased: workers could still earn a living, while residents were protected. The spread of the virus was arrested and there were fewer deaths. It took the Ontario government three weeks to make the same decision.

This pandemic has clearly shown the public that for-profit long-term care is a business. Understanding that makes the reporting by non-profit Canadian news organization PressProgress somewhat unsurprising. In a May 2020 analysis of the four biggest for-profit long-term care chains, Sienna Living, Revera, Chartwell and Extendicare Inc., it was noted that only three out of 35 current board members are certified health care professionals. Most board members have backgrounds in real estate, private health services or pharmaceutical companies, or other corporate sectors like finance and insurance.

The presence of directors with no actual experience and little understanding of how these facilities should be run, or what should govern decision-making when it comes to caring for other human beings, explains a lot about the existing problems in the system.

Hard-working People on the Front Lines

It must be said that not all for-profit facilities are in the same situation as those named in the military report. Incredibly hard-working people on the frontlines are caring for residents with respect, with dedication, and doing their best to make life in these homes as comfortable as possible. They do this all while battling conditions they have no control over.

And it can’t be said that all the problems in long-term care relate to privatization; but privatization, combined with a lack of funding and government neglect, is a major contributor to the problems.

These warnings are not new. They have come in the form of research papers, system reviews, complaints from family and residents, and even commissions like the one held in Ontario after Elizabeth Wettlaufer confessed to killing eight long-term care residents under her care between 2007 and 2016.

It’s just taken a pandemic to expose how pernicious the current system is.

What Can We Do About It Now?

On April 17, 2020, the National Union of Public and General Employees (NUPGE) wrote to Prime Minister Trudeau calling on him to act to extend the provisions of the Canada Health Act.

“It is time that the federal government stepped in to end the travesty that is private for-profit long-term care in Canada,” wrote Larry Brown, NUPGE’s president. “I am calling on your government to extend the provisions of the Canada Health Act to include Canada’s long-term care residences. By doing so, you would ensure that they must meet the 5 principles of the CHA: public administration, accessibility, comprehensiveness, universality, and portability.

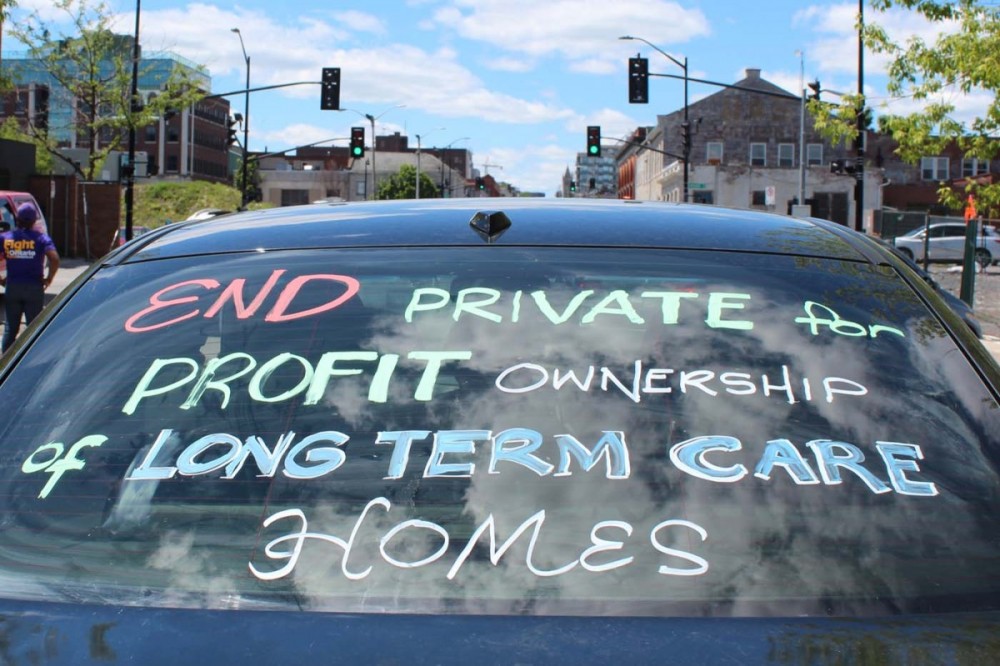

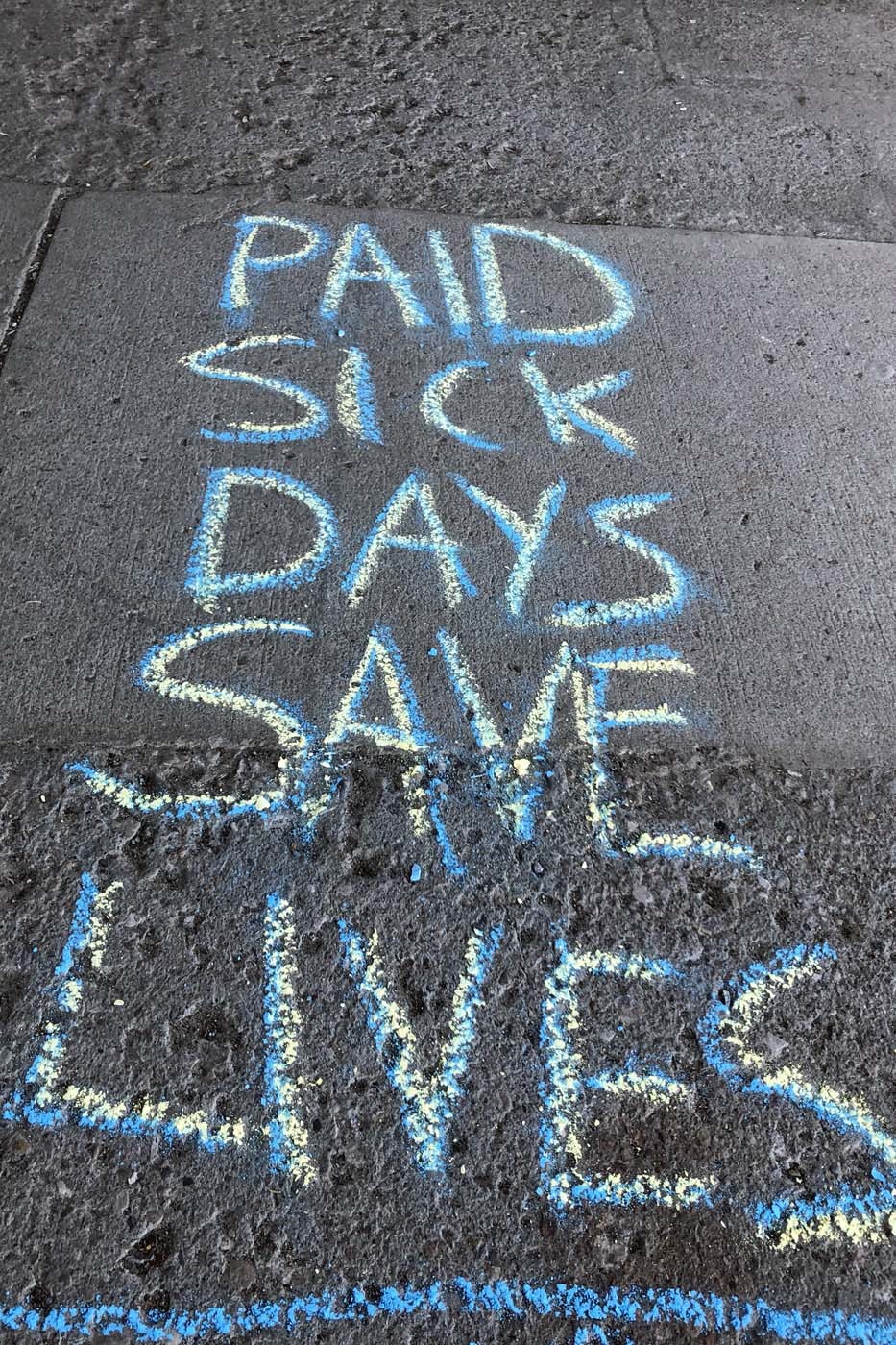

PHOTOGRAPH: BRYNNE SINCLAIR-WATERS

"In addition, your government should take all the steps to adequately fund the necessary support that workers and residents in long-term care in this country desperately need. This funding needs to be ongoing to ensure that a quality public health care system exists in Canada.”

In fact, a recent poll conducted by Abacus Data, on behalf of NUPGE, found that 86 per cent of Canadians support moving long-term care under the Canada Health Act. Eighty-one per cent support the government investing whatever money and resources it needs to rebuild health care and other public services that have been cut. Finally, 77 per cent of Canadians support the government increasing funding for long-term care.

“We need to honour our elders with a system that respects their dignity and has the highest quality of care possible,” said Brown. “Canadians need to know that the care of their loved ones isn’t being compromised by profit-motivated decisions. We need to know that those who care for our loved ones are being treated with the same dignity and respect, which means providing good wages and benefits, decent hours of work and safe working conditions. We need a system that has standards, is transparent and accountable to the public.”

And it’s not just one union calling for this change. The Canadian Labour Congress has released a paper: Lessons from a Pandemic: Union Recommendations for Transforming Long-Term Care in Canada. The report’s first recommendation states that “Long-term care must be brought fully into the public system and regulated according to the principles set out in the Canada Health Act.”

It goes on to say, “The pandemic has shown Canadians how fragile our long-term care system has become from increasing privatization, underfunding and understaffing. The tragedy unfolding in long-term care homes must fortify our collective commitment and dedication to building a transformed, comprehensive health care system that is public, universal, accessible and fair for everyone in Canada. Canadians deserve nothing less.”

We are at a pivotal moment. The Canadian public wants to see lasting change. Now is the time.

As Tommy Douglas once said, “We can’t stand still. We can either go back or we can go forward. The choice we make today will decide the future of medicare in Canada.”

Deborah Duffy is a national representative (communications) with the National Union of Public and General Employees (NUPGE).