Dear Our Times readers: Due to possible disruptions because of the COVID-19 pandemic we will be publishing more stories than usual online from our Spring print issue. Though the issue was completed before the pandemic was identified as a global health threat, we hope you'll be inspired and bolstered by the stories inside. As frontline workers, and so many other workers, are forced to risk their health every day in the face of the pandemic, all the while dealing with increasing precarity, the deep inequities in our society are thrown into ever sharper relief. We hope these articles show that we can and must continue to organize in deeply uncertain times, even if that organizing must happen in novel ways. — Our Times

_____________________________

It’s a tough grind where each day begins like it ends: with you pounding the pavement of the warehouse floor, moving package after package between conveyor belts. You work as quickly as you can manage, risking injury, just to keep up with the demands of your high-stress, low-paying job.

This workplace — which could easily be one of Amazon’s fulfillment centres — is the setting for GigCo: Escape from the Gig Economy, a mobile game created by the studio SpekWork. Game co-creator Cat Bluemke started SpekWork with her colleagues Jonathon Carroll and Ben McCarthy to produce video games about work.

"Jon and I were part of an artist collective in Toronto making performances about unpaid internships,” says Bluemke from Regina, where she and Carroll now work as digital program coordinators for the MacKenzie Art Gallery. “We were drawn to the audience interaction involved with video games and games as a way of discussing labour issues.” Bluemke, the lead designer, and Carroll, the programmer, teamed-up with McCarthy, who created the soundtrack.

GigCo offers a view of a dystopian near-future where gig work employment is no longer the exception but the rule. Information about your job and “self-care” strategies are smoothly integrated into a Facebook-like social media app owned by the same mega-corporation. If you play the game long enough, you begin to encounter subtle hints that an organizing campaign may be underway.

“We started reaching out and tapped into a deep amount of energy and excitement,” says Emma Kinema. PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY EMMA KINEMA

Grassroots Self-Organizing

SpekWork brought an early version of their game to the annual Game Developers Conference (GDC) in San Francisco in 2018, an auspicious year that saw the launch of the pro-union advocacy group Game Workers Unite (GWU). GWU formed as a collective response to a scheduled panel at the 2018 GDC on the “Pros, Cons and Consequences of Unionization.”

The GDC is the world’s largest games conference. It caters to an industry with $43 billion in annual revenues in the United States, surpassing global box office figures for film. However, video game workers are increasingly speaking up about the price they pay for the industry’s double-digit annual growth: long periods of mandatory or tacitly required overtime known as “crunch,” unchecked racism and gender discrimination, unequal pay, and abrupt layoffs even after games make record profits.

According to GWU co-founder Emma Kinema, who is based in California, “The panel was clearly slanted towards being anti-union. Myself and some others started organizing online, figuring out how to get some of us out there, how to make buttons and zines, and have a pro-union voice in the crowd.” Kinema, a queer trans woman, has worked in the games industry for the better part of the past decade for everything from small indie studios to mobile game developers, virtual reality companies, and large “AAA” studios who make blockbuster games. “We started reaching out and tapped into a deep amount of energy and excitement. It felt like we could make this a turning point in the industry.”

The games industry is not historically associated with unions; however in 2016, voice actors with SAG-AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild - American Federation of Television and Radio Artists) struck against 11 video game companies over demands for better pay and protections from vocal stress. A month before the 2018 Game Developers Conference, game developers with the Syndicat des Travailleurs et Travailleuses du Jeu Vidéo (STJV) in France went on strike against their employer Eugen Systems for pay irregularities and failure to pay overtime.

GWU’s intervention and the resulting press coverage brought an unprecedented level of attention to the question of unionizing the games industry. “We made new connections at the GDC, then took that energy and brought it back to our respective cities and studios. Now we’re part of an international movement with 29 local chapters,” says Kinema.

GWU has a presence in 12 countries, including groups in the Canadian game production hubs of Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, and Vancouver. There are nearly 600 studios in Canada with over 20,000 full-time employees. Sixty per cent of these employees are concentrated in 26 large studios with 100 or more employees, while 25 per cent work in 241 small studios with five to 25 workers.

Carolyn Jong’s early academic work focused on Gamergate, a misogynist harassment campaign that targeted prominent women in the video game industry. PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY CAROLYN JONG

Unifying to Stop Harassment

Carolyn Jong and members of GWU-Montreal spearheaded GWU’s first zine, a self-published strategy guide that playfully advertises “tips for beating all the bosses” with a cover that mimics the aesthetic of the classic video game magazine Nintendo Power.

Jong studied the games industry in graduate school, then started making games through an incubator organized by Pixelles, a non-profit with a focus on supporting women in game development. Her academic work focused on the phenomenon of Gamergate, a misogynist harassment campaign beginning in 2014 that targeted prominent women in the industry. “The main reason we see any improvement at all is because of grassroots movements,” says Jong. “That’s where you get Gamergate as a reaction to people trying to change things for the better.

“Gamergate had a big impact on my friends and colleagues. People close to me were living in fear. Some considered leaving the industry, and became hesitant about talking about things openly online or being critical,” says Jong. Alison Rapp, a Seattle-based Nintendo employee was fired in 2016 after being subjected to months of harassment and intense scrutiny of her online activities that drew the ire of anti-feminist gamers.

Jong, who now works in the industry as a freelance artist, sees an important connection between these very public cases of harassment and the growing interest in unionization. “An unorganized workforce is a workforce without any real voice in the workplace and how it’s run. And that includes marginalized workers in the industry — women, people of colour, queer folks, and people with disabilities — who have been under-represented for a long time. They face systemic barriers to working in games, and if they find work, they experience more discrimination and harassment. That makes it less likely that they’ll stay.”

Marginalized Workers Lead the Way

“For everybody, and especially for marginalized folks, being able to bargain collectively and get standardized contracts increases our odds of being able to stick around,” says Morgan. A member of Game Workers Unite – Toronto, Morgan’s name has been changed to protect her identity as a worker organizer. “We want games to be an industry where people can have long careers like in other industries where you see strong unions.”

Game companies often expect their employees to accept extreme workloads but offer little by way of job security. In a particularly galling example, game developer Activision Blizzard — one of several industry giants that are publicly traded — cut 800 jobs in 2019 despite posting record-setting revenues of $7.26 billion in physical and digital sales.

Morgan worked as a Quality Assurance (QA) tester — effectively an entry-level position in the games industry and one that involves rigorous error testing — at an indie studio in Toronto with about 15 employees. The studio had a “no crunch” policy; however, there was still a big difference in the working conditions between contract and permanent employees. Over a year and a half at the studio, Morgan cycled from contract to contract, each one usually four months in length. These were sometimes extended only a week before expiry.

“Speaking as a trans woman, it’s hard to stomach when there is an implicit hierarchy in place. QA work is treated as a lower tier of work,” says Morgan. “Benefits were never on the table, whereas permanent workers automatically received them. Raises were never on the table — until I brought it up.” Morgan currently works in tech and noted that tech jobs tend to offer more stability. “I can’t afford to return to the games industry right now.”

Remy, who also identifies as trans, and whose name we have changed to avoid reprisal from employers, worked as a QA tester with a major studio in Montreal for almost two years. Remy spent over 2,500 hours working on a multi-million dollar title yet remained a temporary contract worker for the complete duration of her employment. “At first I was hired on a one- month contract, then a three-month extension. There was talk about a six-month contract, which wound up being three months, then another three months,” says Remy.

She worked for 19 consecutive days during a crunch period leading up to the title’s planned release date. “I worked for 10-12 hours on weekdays and between 6-8 hours on weekends. It’s kind of sad, but at the time I didn’t feel like it was that bad because I heard about people who worked 30 days straight,” says Remy. “In the end, even with our whole team crunching, the title was still delayed and we had to do a second period of crunch later on.”

Remy noticed members of GWU handing out information flyers outside her workplace and later attended a panel hosted by the group at a Montreal anime convention. Now she wants workers to have a collective voice so they can address depressed wages in the industry. While “getting paid to play games” sounds nice, the reality is that pay starts at minimum wage. The detail-focused, repetitive nature of QA work bears little resemblance to casual play.

On her project, Remy spent over 120 hours on collision testing, which involves forcing characters to walk, roll and jump onto every possible surface — essentially the digital equivalent of banging your head against a wall. With her experience and the specialized skills she’s developed, Remy makes only $1.25 over the Québec minimum wage. Meanwhile, video game companies receive generous tax credits from the Québec, Ontario and B.C. governments that subsidize up to 40 per cent of their labour costs.

Reese, another game worker who spoke about their experiences on the condition of anonymity, attended a game development program at a Toronto college and was one of a handful of students in their class who found work in the industry soon after graduating. The boss at Reese’s mobile games studio was known for screaming at employees for their tiny oversights. Because it was a small start-up with no HR department, any worker’s complaints were directed to the same boss.

“At one point we did a month and a half of crunch where we were expected to stay every weeknight until 10 p.m.,” says Reese. After sticking it out for two and a half years, Reese eventually received a coveted promotion to a more creative role; however, it was short lived. “I lasted six months before working myself to exhaustion and they unceremoniously let me go. I later heard that they did the same thing to several people after me as well.”

Enough is Enough

Both tech and video game workers have initiated an unprecedented wave of collective actions over the past two years. On November 1, 2018, Google workers organized a walk-out over the company’s “forced arbitration” policy, which prevented employees from pursuing issues like sexual harassment through the court system and speaking out publicly about their experiences. Twenty thousand Google employees around the world, including in Toronto and Montreal, participated in the action, forcing the company to end the practice of mandatory private arbitration.

Although Google publicly adopted a conciliatory tone towards this workplace organizing, with the company CEO even “endorsing” the walk-out, two female leaders claimed retaliation and four of the seven core organizers were no longer at the company eight months later. In November 2019, news broke that Google had hired IRI Consultants, a well-known union avoidance firm, and less than a week later the company fired five employees involved in union organizing. Three out of the five fired workers are trans women.

In May of 2019, over 150 workers in Los Angeles at Riot Games, creators of the League of Legends online strategy game, walked out over their company’s use of forced arbitration and its toxic workplace culture. Later that year, Riot paid out $10 million to women who worked for the company in order to settle a gender discrimination lawsuit.

“The walkout changed the tone and tenor inside of Riot Games. This was the first public example of successful workplace organizing to come together and improve things in the industry. So many workers at different studios took note and are citing it as a source of inspiration,” says Kinema.

“Marginalized people are taking risks and leading the way,” adds Jong. “People have been organizing in those communities for a while now — against racism, sexism and other forms of discrimination, which means people have some experience with collective action and organizing. Out of necessity we’ve had to organize already. That helps. Though there’s also the reality of organizer burnout that works in the opposite direction.”

Support from the Labour Movement

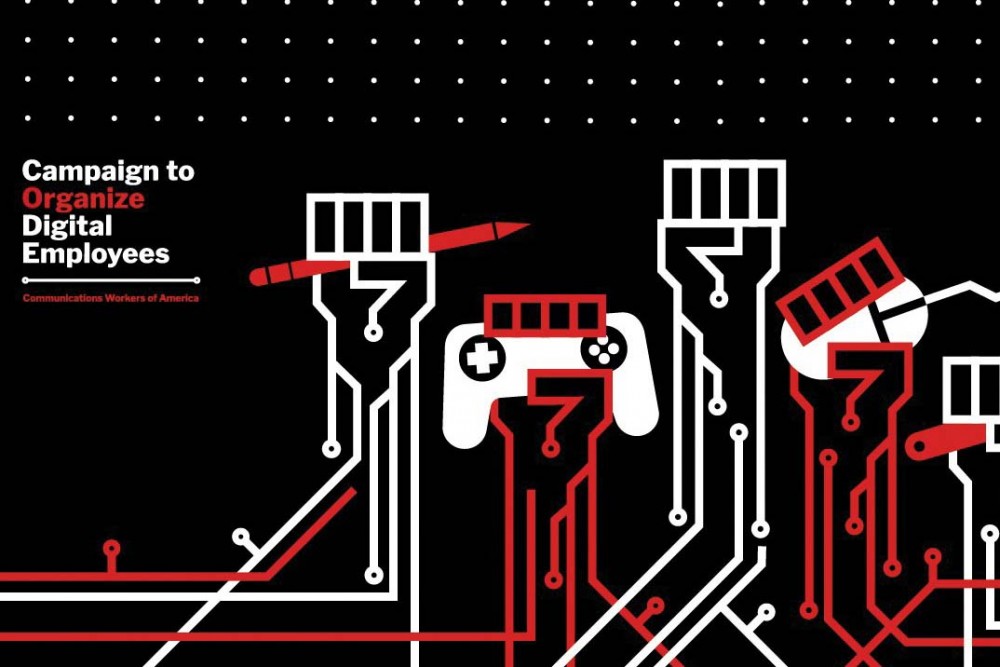

In early 2020 the campaign to unionize the video game industry entered a new stage when GWU announced a partnership with the Communications Workers of America (CWA). The CWA simultaneously launched CODE — the Campaign to Organize Digital Employees — and hired GWU co-founder Kinema to lead the initiative.

“We are merging all the wonderful worker self-organizing we’ve seen with the deep experience and knowledge of the labour movement. The coupling of this wealth of experience with this new sense of energy and direct democracy is very exciting,” says Kinema.

The four components of CODE’s logo are a reflection of the campaign’s broad, wall-to-wall approach to organizing the game and tech industries: a wrench for hardware, a stylus for software and design, a brush for artistry, and a hand for service work. “A great many talents go into making these industries and we are stronger when everyone is together,” says Kinema.

IMAGE: COURTESY CWA-CANADA

Making this labour visible is a political project — to reach consumers, and to help workers understand that when their passion is being exploited to make them work harder, this isn’t just an individual sacrifice, but a systemic problem that requires a coordinated response. Shining any daylight on game labour runs counter to the desires of big studio heads, such as Dan Houser, the Rockstar Games executive who famously commented that games are “magical” because it’s “like they’re made by elves” and that consumers “gain something by not knowing how they’re made.”

The UK chapter of GWU was the first to announce a formal partnership with a trade union when they allied with the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain (IWGB) in late 2018. The IWGB is a relatively new union, founded in 2012 and known for its vibrant campaigns and high-participation strikes with precarious workers including university cleaners and gig economy couriers.

In Montreal, GWU has developed a close working relationship with the Syndicat des Travailleuses et Travailleurs Autonomes du Québec (S’ATTAQ), a freelancers’ union affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). They have co-hosted “know your rights” training and partnered to support individual workers with workplace issues.

“We see some overlap because a bunch of people working in games are freelancers, like myself,” says Jong. “This is part of laying the groundwork for future organizing efforts: getting folks feeling confident and prepared to do the hard work of having conversations with co-workers, and planning out collective responses to problems they are identifying at work.”

Katherine Lapointe, a union organizer with CWA Canada, started meeting with members of GWU in Toronto soon after the group formed in 2018. She sees a connection between the issues game workers are identifying and the issues CWA’s members are facing in digital media organizations like VICE, Buzzfeed and the National Observer. “Launching the CODE campaign is a way to bring workers together to figure out how a union like CWA could offer material support,” says Lapointe.

With financial assistance from CWA Canada, GWU-Toronto was able to have a presence at the Hand Eye Society Ball, a marquee event attended by hundreds of game makers and video game enthusiasts each year. The Hand Eye Society is a local non-profit with a mission to showcase games as a form of creative expression rather than just a commercial product. Another sponsor for their event is Ubisoft, one of the world’s largest game companies. Ubisoft is headquartered in France with North American offices in Toronto, Montreal, Halifax, Québec City, Saguenay (Québec), Winnipeg, San Francisco, Atlanta, and Cary (North Carolina).

“So many workplaces operate globally, especially across the U.S.-Canada border, which means that it’s important for unions to operate across borders and support each other with coordinated campaigns across the globe,” says Lapointe. The campaign is still in its early stages, but workers have already reached out from small and mid-size studios as well as very large international companies.

Unwritten Futures of Work and Play

Johanna Weststar is a professor at Western University who studies the games industry. She conducts a biennial survey of video game workers known as the Developer Satisfaction Survey. The results of the 2019 survey, in which over 1,100 workers participated, suggested that the frequency of crunch may be on the decline. Forty-two per cent of workers cited crunch as an expected part of their job compared to 53 per cent in 2017. The reported experience of 60-90 hour work weeks during crunch also dropped from 43 per cent in 2017 to 32 per cent in 2019.

When asked if there was equal treatment and opportunity in the games industry, 65 per cent of respondents answered “no,” which is actually up from 50 per cent in 2017. This result could be read two ways. One reading is that things could be getting worse before they get better for marginalized workers. Another possibility is that the work of these activists and their allies has served as a dramatic wake-up call. Their mobilizing has alerted the broader workforce to deep inequities and injustices within their industry.

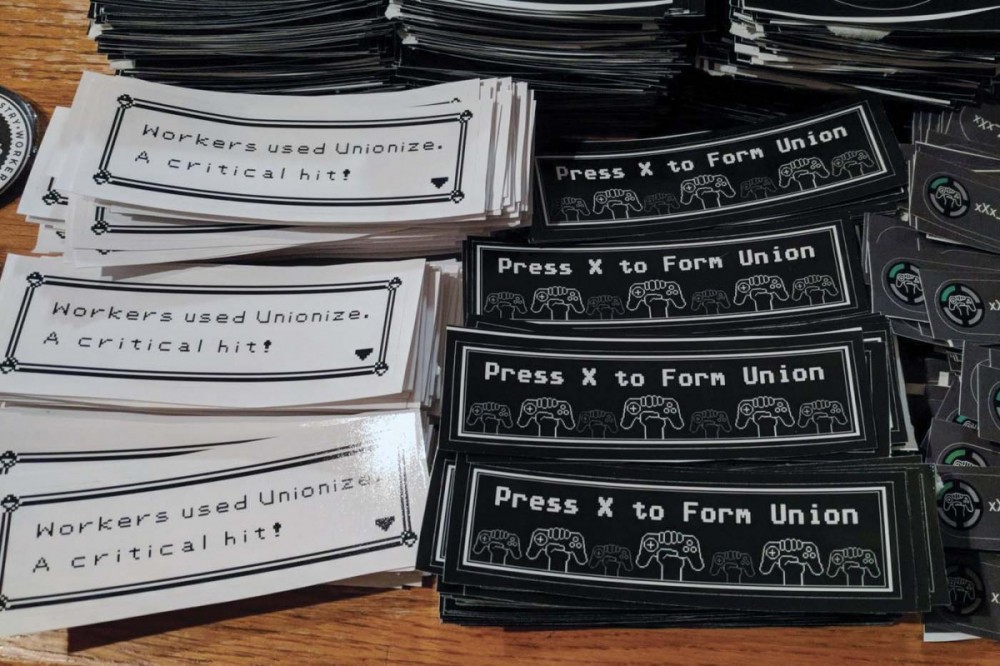

PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY GAME WORKERS UNITE

The problems are now well-defined, but how can the task of organizing together to create solutions be taken to the next level? “It feels like we are entering a second wave of organizing, where workers are increasingly connected and thinking in more comprehensive ways. They’re asking: how do we build power, not just in sheer numbers, but in relationships and leverage,” says Kinema.

Bluemke and SpekWork recently connected with GWU-Toronto. They are interested in developing a co-operative mode for GigCo: Escape from the Gig Economy, where two people can play simultaneously. Bluemke envisions having a physical arcade cabinet so that people can play together in the same space, and perhaps spark up a conversation about their own labour issues.

In the current version of GigCo, workers discreetly use the company’s own messaging app to communicate with each other about workplace organizing. They have little choice due to the lack of common social spaces. But they do so at their own risk. Bluemke’s collaborator, Carroll, highlights the real world example of food delivery app Foodora surveilling workers and using its platform to send anti-union “push notifications” to couriers in the lead-up to their union vote.

More secure alternatives exist for coordinating digital campaigns and communications, but first organizers have to meet workers where they’re at, whether that’s on Facebook, at a professional conference, a social event, outside their workplace, or at an anime convention. For this reason, the grassroots organizing approach of groups like GWU will continue to serve as the foundation of any future success in uniting the games industry.

“Game workers have analytical mindsets, so they immediately understand the value of tried-and-true labour tactics like workplace mapping, building an organizing committee, and campaigns,” says Morgan of GWU-Toronto.

Workers implicitly understand the connection between labour organizing and career sustainability. “When people approach GWU, they are usually in their late 20s or 30s, and looking on the horizon to see if it is possible to have a future in the industry,” she says. “I would like to be able to look down the road 10 years and be able to say, of course I’m still going to make games.”

Ryan Hayes is a cultural worker and researcher based in Toronto, where he is a board member with the Mayworks Festival of Working People and the Arts.

If you like what you're reading and want to subscribe, please go here. Thank you!