Indigenous peoples make up only about five per cent of the world’s population but manage 28 per cent of the world’s land surface and are de facto guardians of 80 per cent of the world’s biodiversity. Eriel Tchekwie Deranger presented these extraordinary statistics at a two-day October conference called Labour Confronts the Climate Crisis. Hosted by the Ontario Federation of Labour, the online conference allowed trade unionists to dive deep into the issue and explore the unique role unions can play in shaping climate action.

Deranger, the director of Indigenous Climate Action, set the stage for the conference and cemented the vital link between Indigenous peoples and climate change. She noted that, in violation of its treaties, the Canadian government states that Indigenous peoples have control over only 0.2 per cent of the land in so-called Canada, while the other 99.8 per cent is deemed crown land, with the government deciding how it is used.

This centuries-long dispossession has always been an attempt to rob Indigenous peoples of their ability and their responsibility to be stewards of the land and water. Deranger emphasized that when Indigenous peoples lose that stewardship, extractivism and its consequences take hold, like the Alberta tar sands wreaking havoc on ecosystems all around Deranger’s home community of Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation.

She was clear: any solution to the climate crisis must be led by Indigenous peoples and requires overturning colonial systems of oppression.Labour Confronts the Climate Crisis featured an incredible lineup of political thinkers, climate scientists, economists, and researchers — people we should all be listening to.

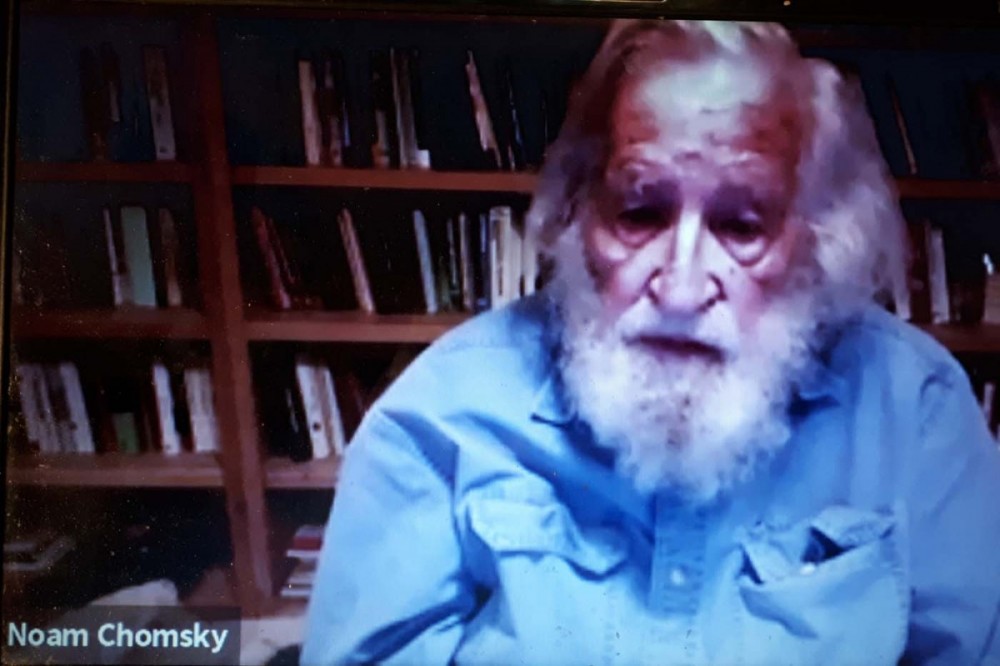

Kicking off the Friday night session along with Deranger was renowned intellectual Noam Chomsky.

Noam Chomsky PHOTOGRAPH: OUR TIMES

Chomsky situated the crisis with an eye to history, and drew parallels back to his own childhood in the 1930s, during the Great Depression, when unions had been crushed by state violence. Back then, like today, things looked bleak. But unions rebuilt and, with a wave of sit-down strikes across important industries, created such a threat to the existing social order that the ruling class was forced to implement the original New Deal that transformed American society, created new social programs and redistributed massive amounts of wealth and control to workers.

Today, 50 years of neo-liberalism have impoverished workers almost back to 1930s levels and shredded safety nets. Now the climate crisis threatens our very future. Unions will once again have to rebuild themselves in new and creative forms and wrest control of the planet away from the corporate class.

Seth Klein PHOTOGRAPH: OUR TIMES

Seth Klein, founding director of the BC office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, looked at what it will actually take to address the climate crisis, using history as our guide. His recent book, A Good War: Mobilizing Canada for the Climate Emergency, looks at how Canada completely retooled its economy during the Second World War, and did so in a matter of months. With only one third of our current population, Canada produced more military vehicles than Germany, Italy and Japan combined — and built the world’s fourth-largest air force.

Klein was clear that we can rise to the climate challenge before us, just like we did in the Second World War, but unions have to drive that effort. “Every large employer needs a convincing plan with clear dates to get to carbon zero. If governments are slow to mandate it, unions should bargain it. If it’s rejected, occupy the workplace. Think of it as the next generation of sit-down strikes, and invite local teenage climate strikers to join.”

Economist Jim Stanford, director of the Centre for Future Work, stressed that the fossil fuel industry directly employs only about 160,000 people. That’s less than one per cent of Canada’s total employment. And that industry’s profits are steadily decreasing in relevance. What’s more, we’ve already embarked on the inevitable path to eliminating those jobs, but they are not being eliminated in a deliberate or fair way.

We don’t want to repeat the devastating scenario that followed the collapse of the cod fishery in Newfoundland, so unions must be proactive. Stanford demonstrated how we could transition all workers out of fossil fuel jobs in 20 years — without a single layoff. Doing so would require investments in early-retirement incentives, retraining programs, relocation services, and support for alternative jobs.

Divesting from Fossil Fuels

The remainder of the conference focused on pension funds and how, or if, unions can use them for good. One thorny question is the role of divestment as a tool in the fight against climate change. From large charitable foundations to university campuses, the movement to divest from fossil fuels is gaining serious momentum. Days before COP26, the massive Ford and MacArthur foundations announced their plans to shift their investments out of fossil fuels.

Institutions in Canada are following suit. Just weeks before COP26, both the University of Toronto and Simon Fraser University announced they will fully divest their endowment funds from fossil fuels. U of T has further committed to moving 10 per cent of its fund into “sustainable and low-carbon” investments by 2025. These historic decisions are results of almost a decade of organizing by students.

Many speakers underlined that divestment may have limited financial impact but can be very effective as a political tool. Democratic institutions, in particular unions, can use it to make a powerful statement and undermine the social legitimacy of the fossil fuel industry.

Is Ethical Investing Effective?

When it comes to where money should go, is ethical investing effective? Speakers offered a range of perspectives and supplied critical insights on ethical investing, its limits, and that it often amounts to green washing. As well, trying to invest in less-polluting companies actually does little to impact climate change (and can often mean investing in anti-union corporations like Apple and Google). Experts were clear: ethical investing is not about what finance can do for the climate, but what the climate crisis will do to finance.

Finally, speakers concluded that there are a number of important actions unions should take regarding their pension funds, including demanding transparency and input into how funds are being invested. Unions can also advocate for investing in community-led renewable initiatives, and they can help these initiatives scale up.

The final panel recognized that while pensions do have a role to play, ultimately our true power lies elsewhere. As workers and unions engaged in the climate fight, it’s clear that we must go beyond pension-board tables and the confines of capital markets.

James Hutt is a labour organizer, writer, and climate activist on unceded Algonquin Anishinaabe territory (Ottawa).