It is a devastating time for GM autoworkers in Canada and the United States. On Monday November 26th, 2,500 autoworkers in Oshawa, Ontario, learned that their assembly plant would close after a century of production. The next day, autoworkers in Michigan, Ohio, and Maryland were told the bad news. As if industrial workers in Detroit and the Mahoning Valley of Ohio have not gone through enough already. The Mahoning Valley lost all five of its steel mills in the late 1970s and early 1980s, leading Bruce Springsteen to compose his mournful ballad "Youngstown."

The staggered timing of the announcements revealed much about GM's thinking. It was clearly more worried about the U.S.'s reaction than Canada's. By timing the Oshawa announcement earlier, GM tried to soften the political blow in the United States.

GM was right to worry. When told the news, Trump raged on Twitter, channelling his inner autoworker: "Very disappointed with General Motors and their CEO, Mary Barra, for closing plants in Ohio, Michigan and Maryland. Nothing being closed in Mexico & China. The U.S. saved General Motors, and this is the THANKS we get. We are now looking at cutting all @GM subsidies, including...." (November 27, 2018.) His anger and defiance resonated, with the tweet receiving an astonishing 124,000 likes and over 31,000 retweets.

As expected, resignation and platitudes prevailed north of the border. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau tweeted his thoughts and prayers: "GM workers have been part of the heart and soul of Oshawa for generations — and we'll do everything we can to help the families affected by this news get back on their feet. Yesterday, I spoke with @GM's Mary Barra to express my deep disappointment in the closure. (November 26, 2018.)

The contrasting tone, if not substance, between the two leaders tells us a great deal about our political moment. If we didn't know better, one might think Donald Trump was the more "progressive" of the two. The rise of right-wing populism in the United States and Western Europe has upended politics as we knew it. The right is left and the left is right, depending on the issue.

How else do you explain Trump, not Trudeau, ripping up trade deals on behalf of the industrial worker and negotiating stronger North American content rules in auto manufacturing and even a clause that states 40 per cent of the content of new cars must be made by workers making at least $16 an hour? True, these changes are more cosmetic than real, and 60 per cent of North American autoworkers can still earn less than $16 an hour, but even this modest effort is more than neo-liberal centrists have offered industrial workers. Bill Clinton gave us NAFTA, and Barack Obama and Justin Trudeau, the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

THE LEFT BEHIND AND THE POPULIST UPHEAVAL

There are many reasons for this populist upheaval, but chief among them is the working-class rage born of despair in deindustrialized areas. In 2016, for example, the "Rust Belt 5" of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin and Iowa propelled Trump into the White House. All five of these deindustrializing states voted for Obama twice only to flip to Trump. It is therefore difficult to blame racism alone.

Post-election analysis from Michael Zweig and others has revealed that households earning less than $50,000 per year deserted the Democratic Party in massive numbers. Many deindustrialized areas saw a 20 per cent swing, and Trump even carried union households in Ohio — the same households that Obama carried by 26 per cent in 2012.

America is not exceptional in this regard. Brexit and the rise of right-wing populism in Europe are part of the same pattern. Deindustrialized areas that historically voted for left-wing or liberal parties are shifting their political allegiance in many countries, mainly because of the failure of "progressives" to respond energetically to the crisis, or worse, facing industrial communities.

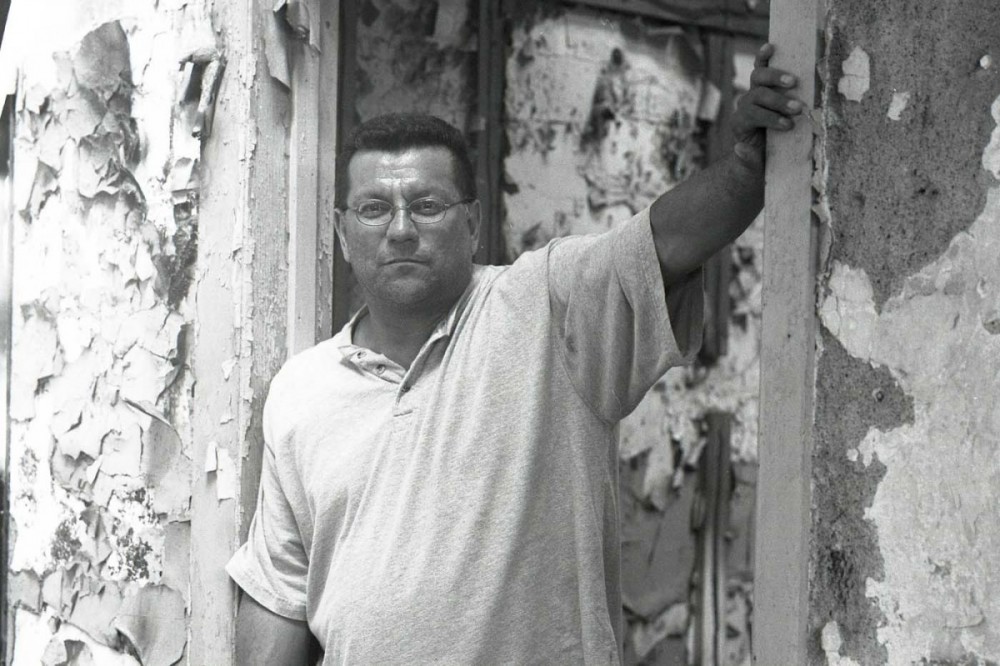

U.S. autoworker Gabriel Solano had three GM plants close out under him during the 1980s and 1990s. He is pictured here by the remains of his home plant, Fisher Guide, in Southwest Detroit. PHOTOGRAPH: DAVID W. LEWIS

These volatile events have prompted considerable debate and conjecture about the root causes and timing of the current social and political upheaval but little sustained research into those "left behind." This phrase is popular shorthand to describe people left behind economically and geographically in deindustrialized areas.

In most media reports, the "left behind" are described as older, under-educated, angry, intolerant, and white. Yet, clearly, white working-class people were not the only ones to experience the seismic shifts of deindustrialization, and there is considerable debate about the ways that race and class interact in deindustrialized areas.

Deindustrialization makes visible deep cultural antagonisms that have long divided industrial societies. Thus, in her study of Kenosha, Wisconsin, anthropologist Kathryn Marie Dudley found that in "America's new image of itself as a post-industrial society, individuals still employed in basic manufacturing industries look like global benchwarmers in the competitive markets of the modern world." In the UK, according to journalist Owen Jones, working-class people are sometimes dismissed as "the remnants of an old world that had been trampled on by the inevitable march of history."

Gabriel Solano took the author and photographer David W. Lewis to various GM sites around the city of Detroit. This abandoned GM assembly plant speaks to the destructive power of corporate disinvestment. PHOTOGRAPH: DAVID W. LEWIS

Working people have reason to be angry. Since the 1970s, corporations have shifted industrial jobs massively to low-wage areas and politicians have either stood by and watched or cheered the corporations on. Cities like Detroit were pulverized, losing 180,000 manufacturing jobs in seven short years between 1978 and 1984. As historian Christopher Johnson wrote back in 2002, "[o]ne of the great ironies of differential regional deindustrialization, which is the standard form of capitalist 'crisis,' is that it hardly leads to revolution, but rather engenders quiescence, the internalization of despair."

RESPONDING TO GENERAL MOTORS

But let's return to the GM closures. Unifor president Jerry Dias, representing Canada's autoworkers, has been nothing if not defiant in the wake of the GM announcements, blasting government inaction and calling on Canada and the United States to work together. He has rhetorically wrapped himself in the Canadian flag, while simultaneously adopting Trump's populist style. Will it work?

Since the closure announcements, industry experts and the commentariat in the media have dismissed resistance to plant closings as futile, saying that this is nothing more than the post-industrial world we now live in. We must accept this reality. Others have pointed to the urgency of fighting climate change, suggesting that these GM plants were victims of a changing world. Both premises are false. The world is not deindustrializing. Everything around us is made somewhere — the question is where will these things be built and how much will workers be paid for their labour?

The environmental issue is little more than a deflection strategy, as there is no reason why GM can't build the next generation of electric vehicles or hybrids in Oshawa or Detroit. Instead, it has chosen to move auto manufacturing to low-wage areas in Mexico and China. Though China is transforming its environmental policy, legislation and enforcement, too often multinational corporations expressly seek out locations that have poor or non-existent environmental regulations. How does more freedom to pollute lead us to a green future on a shared planet

CANADIAN NATIONALISM AND PLANT CLOSINGS

None of this is new. We have been living with deindustrialization since the 1970s. In my first book on the subject, Industrial Sunset: The Making of North America's Rust Belt, I examined the contrasting political responses to plant closings in the U.S. and Canada. The 1970s and 1980s were a period of political and economic uncertainty, as two oil crises resulted in hyper-inflation and massive industrial restructuring. Every other day a major auto, steel, or tire factory closed permanently, putting thousands out of work. The old Keynesian prescriptions seemed to no longer work.

The closed Atlas Steel plant in Welland, Ontario. If Ontario has a rust belt, Welland would be ground zero. PHOTOGRAPH: DAVID W. LEWIS

The Canadian labour movement responded energetically with protests, boycotts, and plant occupations. Many unions adopted a tough no-concessions stance with employers. Plants continued to close, but labour won major concessions from departing companies that softened the blow. Severance packages were fattened and early retirements extended.

More importantly, perhaps, the union movement was able to politicize the plant-closing issue forcing provincial and federal politicians to legislate, in 1970, advance notification of mass layoffs, after the closing of Dunlop Tire in Toronto's East End, and mandatory severance pay and pension re-insurance as a result of a wave of plant occupations in 1979-1980. The most famous occupations were at Bendix Automotive in Windsor, Ontario, and at Houdaille Bumper in Oshawa. At Houdaille, workers occupied the plant for two weeks in 1980, hanging Canadian flags out every window, until they won early retirement for long-service workers and a better severance package. It was also a labour struggle that generated frontpage news.

During these years, Canadian union leaders effectively wrapped themselves in the Maple Leaf flag — setting up a nationalist contrast between Canadian workers and American bosses. This message resonated in the days before free trade. During the occupation of the Tung-Sol plant in Bramalea, Ontario, workers defiantly sang "O Canada" alongside "Solidarity Forever." Quebec workers meanwhile were wrapping themselves in the Quebec flag to the same end.

The favourable political environment in Canada was also important because it forced, or at least encouraged, policymakers to be proactive in their defence of industrial workers. Thus, when Chrysler came begging for a bailout in 1979-80, Canada required that the company reinvest hundreds of millions of dollars in Canadian manufacturing. The U.S. government, instead, demanded steep union concessions (President Jimmy Carter was a Democrat, another betrayal). The contrasting approaches said much about the very different politics then prevailing in the two countries.

The Canadian nationalism of the 1960s and 1970s also led government to nationalize failing industries in some cases. Canada would not have an aeronautics industry today had not the Canadian government taken over de Havilland in Toronto and Canadair in Montreal during the 1970s. Eventually, the plants were sold to Bombardier. Despite recent layoffs, thousands are still employed in the sector.

A THIRD WAY?

However, by the 1980s, public ownership was no longer on the political table, even in Canada. The 1988 federal election, a de facto referendum on free trade with the United States, broke the back of left-nationalism in Canada. The old nationalist rhetoric no longer resonated with the public as it had. Even the New Democratic Party turned away from economic issues.

In my recent book, One Job Town: Work, Belonging and Betrayal in Northern Ontario, I speak to how the Ontario NDP responded to the economic downturn of the early 1990s, which saw another tidal wave of plant closures. Northern Ontario was particularly hard-hit with paper mills in Kapuskasing, Sturgeon Falls, Sault Ste. Marie, and Thunder Bay on the ropes as well as the steel mill in Sault Ste. Marie.

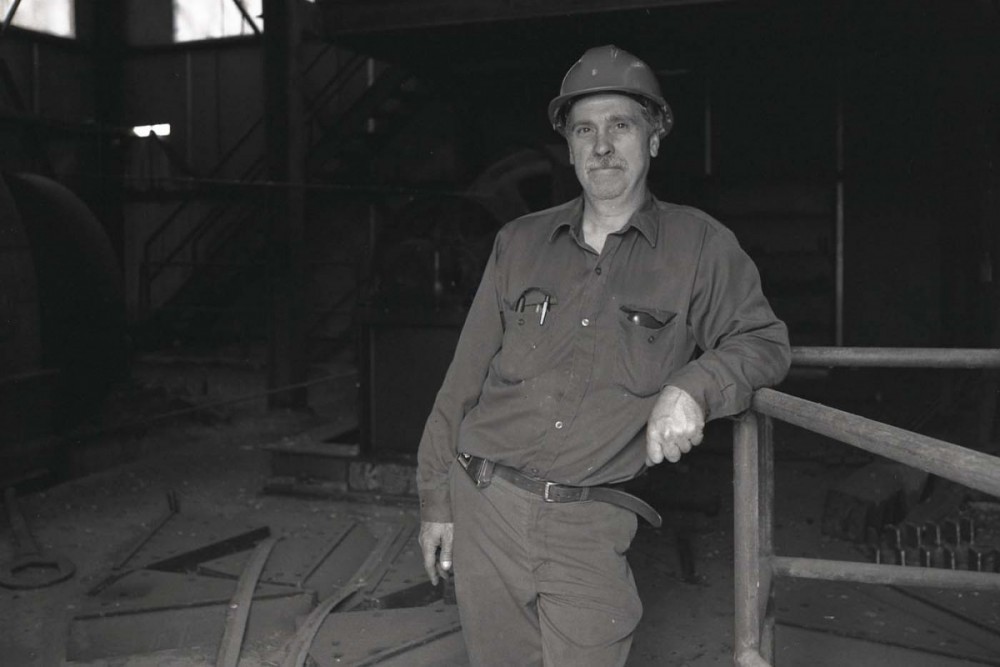

Henri Labelle gave the author and photographer a semi-official tour of the closing of the Weyerhaueser paper mill in Sturgeon Falls, Ontario. PHOTOGRAPH: DAVID W. LEWIS

To stop the hemorrhaging of jobs in the North, but unwilling to consider outright public ownership, the Bob Rae government sought to find some middle ground. The government became a facilitator and chief financier for a series of hybrid schemes to save the plants through a combination of employee or community ownership.

Cobbled together in the wake of plant-closing announcements, these initiatives had mixed results. Three of the four paper mills closed within seven or eight years. Algoma Steel and the Kapuskasing mill are the sole survivors, though they were quickly sold back to the private sector. Mill workers received a handsome return on their shares. So far, this decision has not turned around to bite them, as it has the mill workers in Pine Falls, Manitoba, who lost their jobs soon after the plant was handed back to private enterprise.

Though it pains me to say this, the history of employee or community ownership in North America is not an encouraging one, at least when it comes to large-scale industry. The United States experimented with Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) in the late 20th century. The biggest ESOPs were Weirton Steel in Weirton, West Virginia, and McLouth Steel, downriver from Detroit. Both plants eventually closed. Jeremy Brecher has also written extensively on the failure of industrial ESOPs in the Brass Valley of Connecticut, though he blames union reticence for this result.

DIVERGENT RESPONSES

Overall, American unions were far less defiant in the face of plant closings. Union locals forged in struggle during the 1930s and 1940s died with a whimper. There are many reasons for this. The Cold War served to demobilize the U.S. trade union movement, which purged its more radical organizers and unions. By the 1970s, union leadership had got fat and complacent, and they were unsympathetic to many of the social movements of the time. The fact that many unions faced rank-and-file insurgencies reinforced their conservativism.

There were also outside factors. While it is hard to believe today, labour law in the United States was historically stronger than its equivalent in Canada in several important respects. The Wagner Act, for example, required that companies negotiate close-out agreements after a plant closing. No such requirement existed in Canada.

This provision did not serve American workers well, however, as unions had little to no leverage during these negotiations. In exchange for something symbolic, like a six-month extension of private medical coverage or a lump-sum payment, unions agreed to go quietly into the night. U.S. labour law thus worked against a political response to the plant-closing issue. Canadian unions were free to respond politically, and they did.

Trade liberalization in the U.S. also served to channel union resistance into a fight against imports instead of a deeper questioning of the investment decisions of American corporations, which were exporting jobs to low-wage areas. This tactical mistake was hastened by a program of "trade adjustment assistance" that invited unions to apply for certification that a plant was closing due to the impact of imports. Every closure thus became a victim of imports, as only in those cases would workers get the extra benefits. While American unions gave concessions during collective bargaining in exchange for advance notice, improved severance pay, and preferential hiring rights; Canadian trade unionists won these measures politically, freeing them to take a no-concessions stance.

The political divergence between the trade union movements of the United States and Canada was such that many Canadian unions broke away during this period. There is a pivotal moment in the National Film Board documentary Final Offer when Bob White, president of the Canadian Region of the United Auto Workers, is on the telephone with Owen Bieber, the American president of the international union. Bieber was pressuring White to accept the deal he had already accepted in the U.S., but White was having none of it. The Canadians, like much of the union movement at the time, had adopted a tough no-concessions policy. Soon thereafter, the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) was born. It has since become Unifor, merging with other struggling industrial unions, including my father's old union, the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway, Transport and General Workers (CBRT & GW). With the collapse of trade unionism in the United States, from a high of 35 per cent to 11 per cent, and to a lesser extent in Canada, private-sector unions have turned to mergers as a way to institutionally survive.

SO, IS RESISTANCE TO THE GM CLOSURES FUTILE?

If history teaches us anything, it is that nothing will change unless working people mobilize against plant closings. It is a political issue and should be treated as such. For years, Canadian unions such as Unifor have used what negotiating power they have either to force corporations to reinvest in Canadian manufacturing or to extract promises not to close up shop during the life of the contract. But this is not enough, and the populist revolt is a symptom of this political failure. There is, though, reason to hope.

The neoliberal order and globalization are being challenged like never before and class politics has resurfaced with a vengeance, though not in a way that many of us want. To counter the xenophobic right, it is up to political progressives in the United States and Canada to re-engage with working-class people and with economic issues more generally.

GM's auto-assembly plants may or may not be saved, but fierce resistance will contribute to a wider rethinking of the state's role in the economy and, perhaps, trade deals. More also needs to be done to soften the blow of economic displacement, as the effects of job loss ripple outward through individual lives, families, and communities. Plant closings are an act perpetrated, so they concern us all.

Our Times would like to give a special thanks to photographer David W. Lewis for making his photographs available to us.

Steven High is a professor of history at Concordia University's Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling (COHDS). He is leading a seven-year transnational research project on the politics of deindustrialization.