As Canadians, we are often invited to join in the national exercise of glorifying Canada. But we should first carefully consider that many of our preconceptions may be influenced by nationalist narratives. Without using a critical lens to understand concepts like nationhood and citizenship, or state and newcomer, those of us who are racialized settlers may unwittingly perpetuate the same oppression already meted out to us and to our forebears.

Those of us who see ourselves as beneficiaries of the settler-colonial state have the responsibility of doing the deep, hard work to decolonize. That work requires a redistribution of power and resources, with Indigenous struggles and calls to action always in the foreground. If we occupy any position of power and leadership at all, we must use our power and lead the struggle towards liberation. Being in the boardroom, though, as the token Asian or as a proxy to white power is a lonely and soul-crushing place to be. So we should instead take care to connect and organize with like-minded IBPOC (Indigenous, Black and People of Colour) co-conspirators.

Race-making, in part an institutionalized way of organizing people into racial and economic hierarchies, is fundamentally tied to colonialism. In light of that, how do we, the Asian diaspora, understand the colonial crumbs thrown to us in exchange for our loyalty, and our votes? And by accepting those crumbs that benefit a few of us here and now, how do we harm others who will come after us?

For instance, should we accept that family reunification is considered a privilege within the current immigration system, or should we claim it as a human right?

Similarly, both the myth of meritocracy and the myth of the model minority may have us believe that we deserve our positions and privileges because we earned them through hard work. But it’s important that we look critically at these beliefs and ask ourselves questions like the following:

- What amount of work can validate any settler’s claims?

- How do we measure merit?

- What is our relationship to the land?

- What kind of justice do we aspire to, when Canada is founded on, and continues to benefit from, stolen land, bodies, and labour?

- Since “Asian-ness” is a colonial construct, and racism exists also within the Asian diaspora, how do we build solidarity without internalizing and perpetuating colonial ways of being and doing?

What is “Asian” Anyway?

What does being “Asian” — a category as wide as a continent and beyond — even mean? Though the category is a construct imposed on us, increasing anti-Asian hate and our experiences of that hate are very real. So let us take a moment to reflect on the causes and effects of the uptick of anti-Asian racism in Canada and in all white settler colonial states.

We must first anchor our understanding in history and systems. What came before becomes the present and, without intervention, history's trajectory into the future is only predictable. Without people actively and consistently challenging the status quo, history has a way of repeating itself.

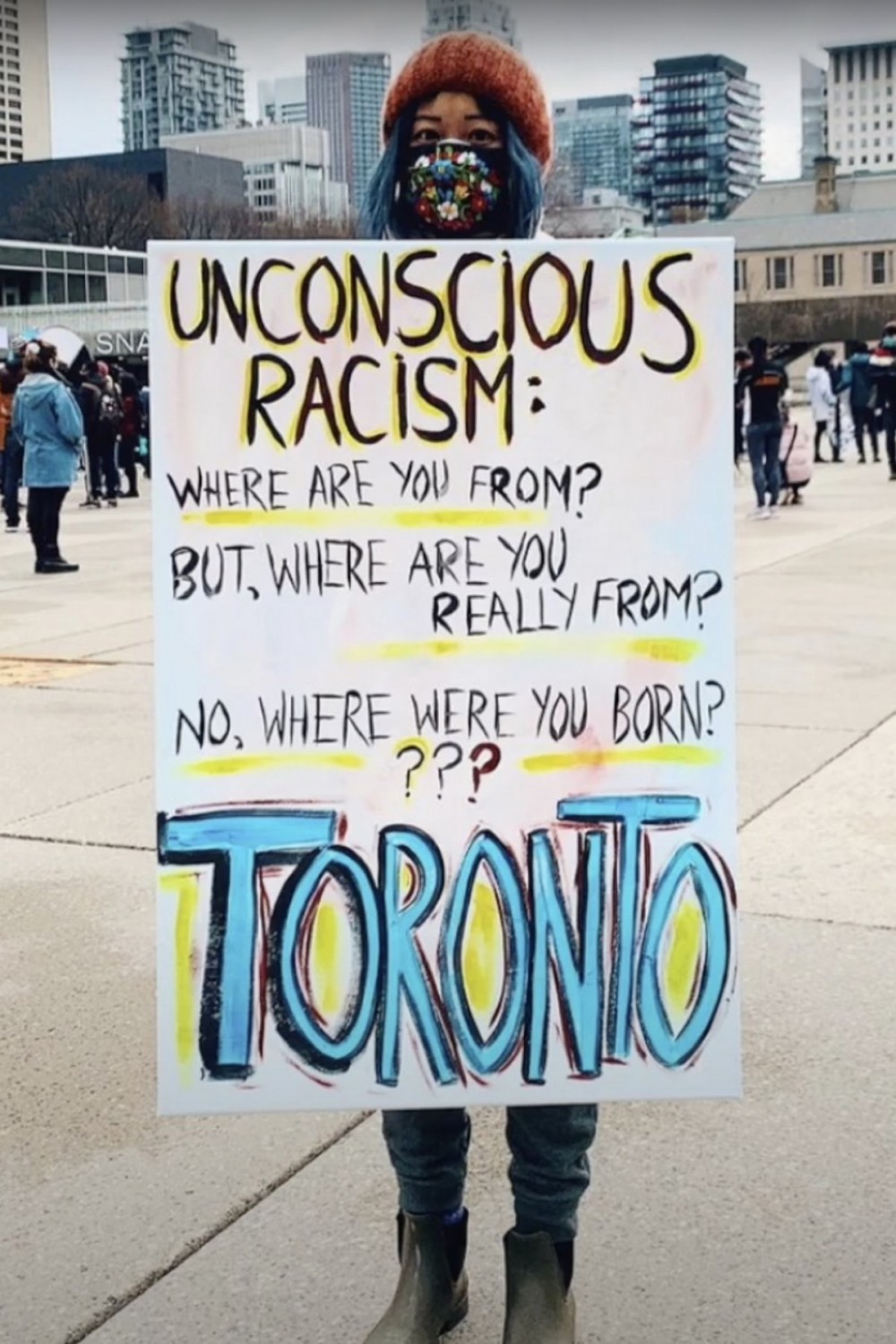

IMAGE: STILL FROM THE DOCUMENTARY TORONTO SOLIDARITY RALLY AGAINST ANTI-ASIAN HATE 2021.

Racism may seem dormant at times, but it can easily be activated and shifted into new, no less dangerous forms. So when we see political flashpoints, we must ask ourselves: Why now? We would do well to learn the relevant history and reckon with its impact on the present.

Oppression is a revenant. If you believe it is a thing of the past, I invite you to scratch the surface of your own family’s history. Which stories are revealed, and which questions are left unanswered, avoided, shushed away? Can you trace the intergenerational trauma that still haunts the living today?

One of the ways historical violence lives on in the present is through silence and denial. Both hide the truth from those of us who unknowingly inherit pain and dysfunctional patterns. No family is ever perfect, but perhaps it would do us well to investigate a little further: did the dysfunction in our family originate from colonial violence inflicted on our ancestors? Are contradicting accounts of and the inability to talk about family history a result of revisionism or amnesia, both of which may allow loved ones to avoid touching a painful open wound?

We can never heal if we cannot access truth, and that is how oppression lives on like a virus. Unless we break the cycle by first seeking and then telling the truth. White supremacy culture that imbues our workplaces, unions, healthcare, and governance systems is just another version of entrenched oppression, even though, through time, that oppression may take different forms. Slavery, for example, may be seen by some as an abhorrent practice of the past, but human trafficking and the prison industrial complex, both of which predominantly exploit racialized people, exist in its place.

And though many may point to the pandemic as catalyzing the rise of anti-Asian racism, that racism is a continuation of the colonial history of these lands and beyond. We need to adopt a long view and apply a systemic lens to any analysis of injustices such as these. We must ask: How have the laws, policies and governments over the past centuries across the conquered lands of European empires shaped the present world?

The Model Minority Myth

Many immigrants pride themselves on their resilience as they grapple with hardships and discrimination, but if resilience does not evolve into resistance, especially through generations, it can become toxic. “Putting your head down, working hard and not rocking the boat” is often necessary for survival, and to overcome immediate difficulties. But dwelling in the psychology of static resilience can lead us to embody, ever more fully over time, the myth of the model minority.

If we assume the role of a model minority, we segregate ourselves from the struggles of Indigenous, Black and other People of Colour. That self-segregation also undermines our solidarity with all marginalized peoples. To be fair, the model minority myth — just another item in the colonizer’s divide-and-conquer toolbox — was and is imposed on Asian settlers by white supremacy. And power relations, an integral part of this imposition, are skewed against those people whose own claim to power has been suppressed through the colonial theft of land, bodies and labour.

The perception that Asians as a social group will not rise in resistance also has its roots in the racist myth of the model minority. That, and the assumption that Asians will remain silent, contributes to them being targeted for racist attacks. What is scarcely taught in the K-12 curriculum and almost never featured in mainstream media, though, is the history of strong Asian resistance throughout the colonial period of so-called Canada. Our stories of joy, resistance, and transformation are largely absent from the public consciousness.

The dearth of Chinese Canadian history, for example, means Chinese Canadian youth in the public education system do not see themselves reflected in the curriculum beyond the legacy and pathos of indentured labour. What else do students learn about the history of Chinese Canadians, beyond the head tax and the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway? Of Japanese Canadians, beyond internment camps? Of South Asians, beyond the Komagata Maru?

Repeating only these stories flattens the complex, multi-faceted and ever-changing realities of diverse communities. In short, it dehumanizes them.

Into that void rush sensational cultural products like the movie Crazy Rich Asians, released even as so many people grapple with poverty, precarity and the other destructive realities of global capitalism. How are both students and workers from Asia to make sense of such reductive portrayals when there are so few other stories — varied, intricate and richly textured stories — to complicate them?

We must widen the scope of stories told about and by marginalized peoples. And, as educators, union activists and community organizers, our assumptions about “Asian-ness” must also be challenged.

Student? Worker? Immigrant?

For many Asian diasporic communities, their very presence in this country is fragile, marginalized, and can be easily erased with a change in policies.

Among those communities are the many international students from Asian countries who come to Canada intending to establish themselves here after completing their studies.

International tuition fees are increasingly funding K-12 and post-secondary education as public resources directed to these institutions continue to dwindle. Aside from the fact that such underfunding is a theft of public money, the international student visa program is inherently exploitative.

Let’s not kid ourselves that these people are students only — many of them are also workers. To afford high living costs, they must work while studying, and they can be found in any conceivable industry: retail, service, construction, culture, academic research and so on.

Indeed, the federal program hints at this logic by permitting students to work up to 20 hours per week and offering them a pathway to settlement after graduation, should the students be able to secure eligible employment within a specific time frame.

Regardless of industry, the common thread shared by these students is an unequal position of power relative to their other peers. At every step of the way, they must ensure that nothing will jeopardize their fragile ability to remain in Canada. The stakes are high and may require achieving a certain percentile in a competitive academic program, tolerating unsafe working conditions to make enough to live on, or ignoring discriminatory treatment in a practicum in order to secure a favourable reference.

The argument that these rules apply to all international students, not just those who are racialized, and therefore are not discriminatory or racist, does not stand. The growing number of international students coming from Asian countries to European countries or to the United States in recent years is well documented and nothing short of dramatic. Increasingly, these students are from middle-class or lower-middle-class backgrounds. Their families may invest their life savings and even take out loans to finance these students’ careers. At the same time, Canadian educational goods are increasingly marketed in Asian countries and government policies have shifted to provide international students a path to remaining in Canada. All this implies the continuation of a colonial strategy: provide the country with a reliable source of labour and the creation of a model minority class along with it.

IMAGE: STILL FROM THE DOCUMENTARY TORONTO SOLIDARITY RALLY AGAINST ANTI-ASIAN HATE 2021

Immigration and labour policies like the Temporary Foreign Worker Program are responsible for much of the 21st century’s version of exploitative work. Work permits issued for workers under this program mean they are beholden to their employers for at least a certain amount of time. Add to this, the feminization and racialization of certain industries, most notably in the caregiving, service, construction and agricultural sectors. Hazardous and segregated labour creates unequal status as well as dangerous working conditions for many female and Asian workers who fear that speaking out will result in gendered and racist violence, or the loss of their job or work permit. Indeed, acquiescing, being grateful to the colonial state, and subscribing to the myth of the model minority are the desired outcomes of such policies.

We simply cannot ignore the intersection of race and class in all of this. As cultural theorist and activist Stuart Hall said, “Race is a modality in which class is lived.” In other words, race is complicated by one’s wealth and status, and we must develop a sharp class consciousness to understand what, in a systemic way, drives our lived experiences. The model minority myth and the term “Asian” itself mask a wide wealth gap. So, once again, we need to ask questions. Who is deemed a “good immigrant”? Who enjoys immediate permanent resident status? Who gets to apply and who successfully enters the country via the points system? What educational, social, and/or economic capital do these people possess?

Globalization has created untenable situations even for this group of “economic” immigrants. Threatened by crises at home and by market economies that negatively affect their life prospects, many choose to emigrate with the hope that they can provide a better future for their children. Yet, because of unequal status, many must toil in isolation, in substandard conditions, far away from their families.

Neoliberal policies have further devastating consequences. They create political turmoil, ecological crises, and maintain colonial legacies globally. They undermine economic stability, social security and grassroots collective action that could promote radical solutions. And they contribute to systemic factors that ultimately lead to families traveling overseas for survival, work and education, however arduous that journey may be.Of those who emigrate, refugees and the undocumented are among the most vulnerable, driven to leave their homes due to wars, violence, and environmental disasters. The bitter irony is that the countries they often settle in, like Canada, are at least partly responsible for creating the conditions which first forced them into insecurity.

Considering all this, if we enjoy relative social and economic privilege, we may ask ourselves the following questions:

- How has my alignment with institutions and the establishment — white supremacist culture — benefited me personally?

- What is my responsibility to act in solidarity with the more marginalized members of society?

- What risks am I willing to take in order to challenge racism?

- How committed am I to challenging racism, even when I don’t think it directly affects me?

- How am I building capacity and solidarity with others to collectively do anti-racism work in the workplace, at school and in union spaces?

We must also give thought to this question: Where do the aggrieved go for support when they experience racism? The poor, those who are gender nonconforming, and those with disabilities face particular challenges as marginalized groups who can suffer multi-layered and compounded discrimination.

We must also recognize that the model minority myth can place an overwhelming amount of stress on many Asian youth and students to perform. Add to that the stigma tied to mental health issues, and inequitable access (which may include language barriers and/or a dearth of counsellors who can relate to their experiences) to health services, and they may suffer in silence.

The precarity of work along with shrinking wages may also lead them to believe that the failure is their own. All this means that our job must be to educate and shine a light on systemic, rather than individual, failures.

What Do I Do Now?

To end on a forward-looking note, here is a challenge for us all as activists and organizers to put foot to pedal, and transform our thoughts into actions using these questions:

- What are our responsibilities as settlers? Knowing what they are, what tangible actions do we take?

- How do we expose and dismantle systems of oppression?

- What do we commit to do in order to advance justice and liberation, in solidarity with Indigenous, Black and other People of Colour?

- What would transformative justice look like in my workplace?

- What do we do to dismantle the model minority myth in our workplaces, schools and union spaces?

- For settlers of Asian descent, what will you do to stop reifying the model minority myth?

- How do we honour the history of Asian political resistance this year?

- How do we nourish a sustained, creative, and collective resistance?

Let’s never give up resisting, and let’s celebrate and care for each other while doing so. To paraphrase Mariame Kaba, the ardent abolitionist activist and visionary: Let’s do this ‘til we free us!

吳玨穎Karine Ng, (佢/she), is a public school educator, organizer and union activist who lives in the stolen, unsurrendered and shared territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. She is on the executive of the Vancouver Elementary School Teachers' Association (VESTA) and the Anti-Oppression Educators Collective (AOEC). She is also a core member of the BC Chapter of the Asian Canadian Labour Alliance (ACLA).

Visit ACLA at aclaontario.ca, and get in touch by emailing aclainbc@gmail.com. To get in touch with AOEC, visit aoec.ca, and @aoec_bcbipoceducators on Instagram.

For further learning about a more balanced history of BC, visit challengeracistbc.ca, watch British Columbia: An Untold History online at knowledge.ca/program/british-columbia-untold-history, and see Winnie Ng’s “Excavating Narratives of Resistance” in Our Times Fall 2020.

All the images accompanying this article appear in ACLA Ontario member Patricia Chong’s short documentary, Toronto Solidarity Rally Against Anti-Asian Hate 2021, which can be seen on YouTube.