It seems only fitting that a highly infectious virus has exposed some of the worst symptoms of capitalism. Workers at the Cargill meatpacking plant in Alberta were forced to double-shift at long-term-care homes to make ends meet, spreading COVID-19 between sites, to give one example. Cargill refused to send home potentially sick workers or provide even unpaid sick leave. Meatpackers at the plant were given financial incentives for showing up to work as the number of workers testing positive for COVID-19 continued to climb. After repeated pleading by UFCW Canada (the United Food and Commercial Workers), the plant ended up closing its doors for 14 days before promptly reopening. Three deaths have since been linked to Cargill, giving just one more example of the callous disregard many employers have for workers.

Now, lockdowns, closed borders, lost lives and economic turmoil have all sparked national discussions about how to recover and, more importantly, how to treat some of capitalism’s worst symptoms to prevent the next crisis.

Some, such as UBI Works, argue that a Universal Basic Income (UBI) will accomplish this. A standard UBI would provide a regular, minimum cash payment to all Canadian citizens with the intent of covering their basic necessities. With the Canadian government currently providing a benefit to workers who have lost their income due to the pandemic, a basic income feels like a logical next step.

From CERB to UBI

On April 6th, the Liberal government began paying millions of Canadians the Canada Emergency Response Benefit of $2,000 per month.

The original terms of the CERB, however, failed to account for nearly a third of unemployed Canadians, leading NDP leader Jagmeet Singh to argue instead for a temporary UBI that would see $2,000 go directly to every Canadian and Indigenous person within Canada right away, not just those who lost work in the pandemic.

On March 23, NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh called on the Liberal government to provide direct assistance to everyone in Canada. PHOTOGRAPH: JOSHUA BERSON

Many argue a UBI can replace discriminatory, means-tested programs meant to restrict the necessary criteria in order to benefit as narrow a group as possible. They also argue that a UBI would lift tens of thousands of people out of poverty and place more power in the hands of low-income workers to seek better pay, benefits and safer working conditions.

In 2017, the Ontario Liberal Government announced a three-year UBI pilot program. The program paid up to $16,989 for a single person and $24,047 for a couple, less 50 per cent of any earned income. Despite being scrapped after one year, by the Ford government, the pilot generated enough data to show how a basic income can potentially help workers.

A joint report by McMaster University and Ryerson University, in partnership with the Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction, found that rather than short-circuiting participants’ motivation to seek or retain employment, as many argued a UBI would, more than three-quarters of people in the program continued to work. Many managed to secure better, higher paying jobs. Nearly 80 per cent said their health improved, with a majority reporting better mental health, more self-respect, and reduced drinking and smoking.

While Ontario’s UBI pilot still applied restrictive criteria, the findings illustrate what many in the labour movement have known for decades: the fight for better working conditions and a robust social safety net is about dignity and security, not laziness.

Workers' Historic Struggles

In 1959, many in the world of medicine declared the war on infectious diseases over. Penicillin and other antibiotics, they believed, had eliminated the need for further study. Less than two years later, however, antibiotic-resistant staph infections appeared, and the war was back on.

Like these mutating infections, capitalism has, for many years, proven its ability to adapt. Still, workers fought hard for treatments meant to eradicate its most debilitating symptoms.

In 1872, for example, at a time when unions were illegal, the Toronto Typographical Union (TTU) Local 91 went on strike as part of the nine-hour movement. Subsequent arrests and protests forced the government to pass the Trade Unions Act, giving workers in Canada the legal right to unionize.

A slew of lawsuits in the early 20th century forced a government report recommending the first instance of a government workers’ compensation program in Canada, providing support for workers hurt on the job.

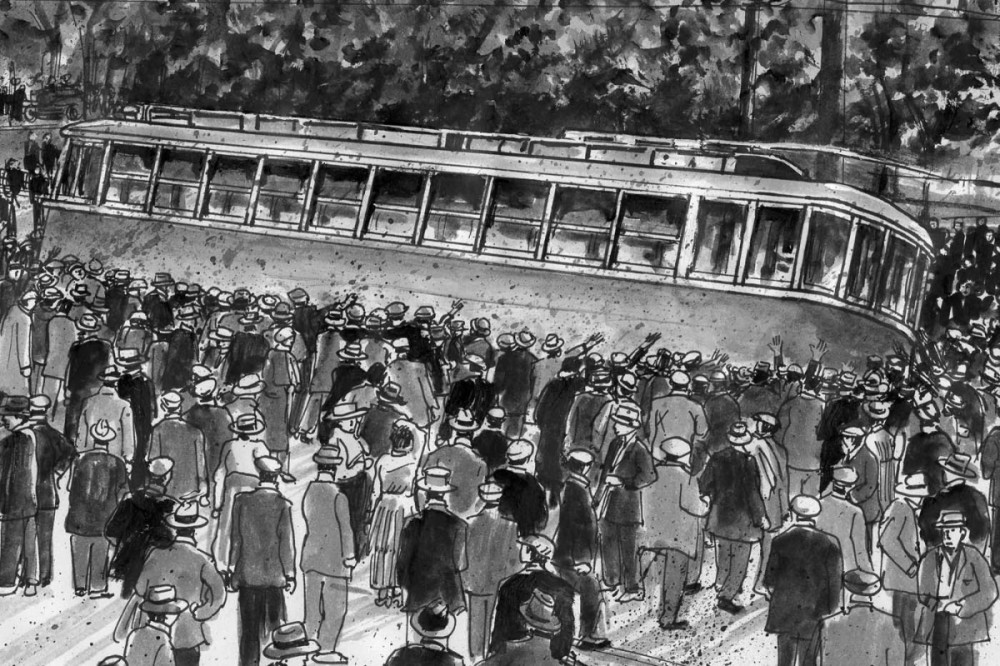

An excerpt from 1919: A Graphic History of the Winnipeg General Strike (Between the Lines). ILLUSTRATION: DAVID LESTER

The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 increased the political power of the labour movement by getting several of its major organizers elected to seats in the provincial legislature while still in jail, with one, John Queen, even serving several terms as the mayor of Winnipeg.

Workers unemployed during the 1930s protested against humiliating worker relief camps and fought evictions, forcing the government to establish unemployment insurance.

Later, building on the success of Tommy Douglas as Premier of Saskatchewan, workers fought for and won medicare, a 40-hour work week and an eight-hour workday.

Capitalism, the Mutating Virus

But the 1980s came and, with them, capitalism mutated in the form of neoliberal governments coming to power across the Western world from Thatcher to Reagan to Mulroney. Slowly, surely, progress was undone through privatization, deregulation, union busting, offshoring and finally globalization.

Taxes and regulations on businesses were relaxed, allowing employers to pay workers less for more work. Automation created greater productivity without an accompanying rise in pay for workers. Bills that curtailed the power of unions contributed to unionization rates in Canada falling from 37.6 per cent to 28.6 per cent between 1981 and 2014, with the biggest losses coming in the private sector.

The mutation of capitalism helped contribute to a modern pre-pandemic economy reliant on low-paid, temporary, precarious gig work. Were a Canadian government to implement a basic income, it would likely allow employers to keep wages and benefits low, propping up the capitalist system that exacerbated the crisis in the first place. It’s not difficult to imagine governments using the cost of a basic income to justify greater cuts to public services like those happening in Manitoba right now.

The Need for Workers' Power

The crux of the problem, then, is the lack of power wielded by workers. A UBI would help workers immediately, but as long as the structures of power are held by capital interests, the unequal power dynamic will continue to erode worker protections. Workers should absolutely fight for a basic income right now, but what we truly need is a long-term power shift.

Such a shift would require new models of unionism and greater union density, particularly in the private sector. This trend appears to have started already. The Lynn Valley Care Home, where poor working conditions helped the COVID-19 outbreak start in British Columbia, recently saw a majority of their workers sign union cards. A wave of unionizations in the long-term-care sector and other private industries could lead to essential workers having the leverage and public support they need for large union drives.

Improving the situation of unions alone, however, will not shift the balance of power firmly enough into the hands of workers. Capitalism cannot truly be cured until people have control over their own work. Perhaps it’s time once again for unions to look seriously at organizing around a transition to worker-owned co-operatives or self-directed enterprises, where businesses are owned by the workers who operate them.

Glitter Bean Cafe window, in Halifax. PHOTOGRAPH: TONY TRACY

What About Worker Co-ops?

While Canada does not have a strong tradition of successful co-operatives outside of Quebec — where more than two-thirds of the country’s co-operatives operate, mostly in forestry — there are smaller, successful examples from all over the country. The Glitter Bean Cafe in Halifax is owned and operated by workers who are unionized with SEIU Local 2. The People’s Co-op Bookstore in Vancouver was founded in 1945 by political and labour activists and has operated for the 75 years since. (They are now, like many independent bookstores, in fundraising mode to make it through the COVID crisis.)

There are also international examples of successful co-operatives that Canadian unions could learn from. The Mondragon Corporation in Spain is the largest worker co-operative in the world, employing more than 75,000 workers with annual revenues in league with those of Kellog’s and Visa. Importantly, each Mondragon co-operative has ties to a specific labour union. In 2009, Mondragon partnered with the United Steelworkers to open co-operatives in the United States. Coop Norge in Norway is run by an elected board chosen by its more than 1.3 million members. In the United Kingdom, Suma is the largest independent wholefood wholesaler while being collectively owned by its employee owners.

Some unions in North America have rejected employee ownership — and many with good reason. Businesses may be seeking to offload debt-ridden businesses by making a quick buck from employees. Likewise, employee ownership for a small group of workers might weaken the collective bargaining potential for unionized workers in the same industry who don’t own their workplace.

The success of Canadian and international co-operatives, however, and especially those which have found success through unionized workers, suggests a path forward. Workers in Canada can cure capitalism not by treating it with antibiotics and giving it a chance to mutate, but by vaccinating themselves against a fundamentally unequal relationship and fighting to control their workplaces.

Nelson Better is a writer of both fiction and non-fiction.