The U.S. presidential election is fast approaching. In this special series, six writers focus on workers, deindustrialization, and the rise of right-wing populism in the United States, England, France, Italy and Germany.

_______________________________

His own delusional self-conception notwithstanding, no one has ever accused Donald Trump of being particularly stable or having a consistent position on complex matters. It would however be excusable to find his love-hate relationship with the American Rust Belt particularly inconsistent. On the one hand, Trump clearly recognizes its political importance. He spent virtually the entire 2016 campaign there lamenting how China and Mexico had stolen the jobs of good people in the region.

Among his most popular photo ops since becoming president are those staged in Midwestern factories, featuring Trump crowing about the ostensible return of manufacturing. When even the most execrable people in the region show up with assault rifles and threaten to rape, murder, or kidnap the Governor of Michigan for closing the state down for COVID, he makes a point of supporting these “good people.”

On May 20, Michigan barbers gave free haircuts to protest Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s emergency orders. Republican State Senator Kevin Daley (centre) sat for a haircut. PHOTOGRAPH: JIM WEST

This, of course, stands in stark contrast to his messaging and behavior toward the big cities of the Rust Belt. Despite these cities sharing the challenges of deindustrialization, Trump goes out of his way to demonize them. Chicago, Detroit and Flint are “hellholes” and “war zones” — their residents are lazy, entitled, violent and need to be treated with zero tolerance.

In July, Trump and his Justice Department initiated Operation Legend and began sending federal agents into some of these Rust Belt cities, as well as others, to “fight crime” in a highly theatrical way intended to help him win re-election. To sell himself as the “law and order” candidate, Trump is waging war on these cities. It is, in fact, a war on the “Black” city.

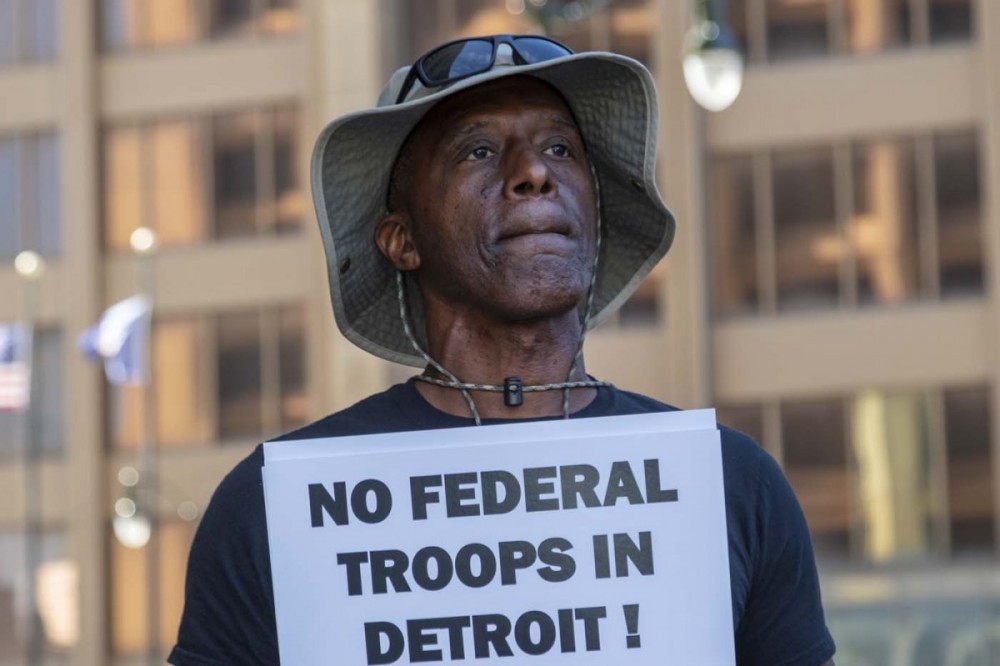

A rally in Detroit on July 31 to oppose President Trump’s plan to send federal police to the city. Protesters said federal money should instead be used for health and income support during the pandemic. PHOTOGRAPH: JIM WEST

What does it take to be a “Black” city? This isn’t a careful act of analytical sociology, so it certainly does not require a city to have a majority Black population. It’s an act of symbolism: It need only be coded as Black by white conservatives. A city with visible Black poverty in a single neighbourhood — that counts. A city where an uprising occurred after an act of police brutality — that definitely counts. A city that is led by a Black mayor — that makes it official right? A city that is home to America’s first Black president — this is too easy.

Trump’s war on the Black city is a last-ditch way to restore his credibility ahead of November’s election. What does it mean when this is the safest strategy he has? Attacking the Black city pays electoral dividends for conservatives. Trump understands that many of his followers are animated by these performances of brutality — such displays confirm their long-held beliefs that these places are filled with criminality, vice, and danger.

My recent book Manufacturing Decline (2019; Columbia University Press) details the ways that reactionary hatred of the Black city in the region has exacerbated the pain of deindustrialization there over the past five decades.

Every region has demographic differences between its urban and rural areas, but the Midwest is unusually polarized on this count. Its rural and suburban areas are unusually white; many of its cities are unusually Black. This creates a binary template for “us/them” politics, one that does not exist to the same degree in other parts of the country. This template has been actively exploited by conservatives (in both parties, but mostly Republicans) since the Civil Rights Movement.

Documented disparities in employment access, housing finance (past and present), and treatment by law enforcement suppress the majority Black spaces in the region. Politicians situated outside the principal cities in Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois run on the “pathology” and “corruption” of Cleveland and Detroit, and when they get into office, they actively pre-empt local laws there, limit the power of the cities’ mayors to attract businesses, and incarcerate more of their citizens. This, of course, makes the pain of deindustrialization worse and the prospects of economic reinvention more remote.

Public displays of cruelty toward the Black working class and the places they live have long worked to shore up the loyalty of the white working class. Sending troops into Detroit or the south side of Chicago under “law and order” battle flags is not even a particularly disguised theatre of that war. The fact that it is the president’s safest pathway to re-election — and is currently keeping his base together — should speak volumes about the role of anti-Black racism in the modern Conservative Movement, and the American Rust Belt.

___________________________

This series is sponsored by Concordia University’s “Deindustrialization & the Politics of Our Times” research project, funded by Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Jason Hackworth is Professor of Geography at the University of Toronto.