This pandemic must be a wake-up call about the importance of home and why we should all have one.

Public health mantras of “stay home," "maintain six feet of distance from others” and “wash your hands frequently” are exactly what you cannot do if you are homeless. In fact, many local decisions necessitated by the pandemic to protect people have worsened day-to-day survival for people who are homeless.

Libraries and community centres have closed, leaving people without access to washrooms, a computer, free newspapers or a phone. Community meal programs have ended and people can receive a meal only in a takeout container handed to them at the door. Day drop-ins that offer showers, clothing and other programs have had to dramatically reduce the number of people they are allowing in.

The reluctance of public health officials to pay better attention to this population defies reason, given the science of disease transmission.

The historic fight for housing as a right

In 1998, the activist group Toronto Disaster Relief Committee declared homelessness a national disaster. Jack Layton, then a city councillor, went to the Big City Mayors Caucus of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities and convinced them, on the basis of our group's work, to also make that declaration. Across the country, local governments followed suit and passed similar motions. This was a time of huge housing demonstrations across the country, supported by the union movement.

Jack Layton speaking at a National Housing Day rally in Toronto in 1999, organized by the Toronto Disaster Relief Committee. PHOTOGRAPH: CATHY CROWE

Our work led to a federal homelessness program that essentially provided funding similar to disaster relief for shelters and other social service organizations. It did not win the reintroduction of a national housing program. After the Second World War, returning Canadian veterans, faced with a housing shortage, fought hard for what would eventually become this country's near-universal national housing program by the 1960s, much like medicare. Through the 1980s and 1990s, though, that housing program was dismantled by successive federal governments. Provincial governments further slashed funding, and construction was handed over to the private sector.

Without the re-implementation of a national housing program it’s no surprise that homelessness has dramatically worsened. What’s needed is social housing, or more accurately rent-geared-to-income housing, along with increases to social assistance and the minimum wage.

People have been left, and left for a very long time, in overcrowded shelters. In many communities, faith groups responded years ago to the shortage of shelter beds by opening their auditoriums or basements, usually in the winter. In 2016,Toronto added three temporary dome-like structures to shelter hundreds of people. Some day drop-in centres now sleep women, some as old as 80, overnight on mats or in chairs. None of these band-aid measures meet city shelter standards, or even the United Nations’ standards for refugee camps. Last year there were reports of outdoor encampments set up all across the country, no longer in just the big cities.

Shelters are breeding grounds for infection

Shelters by their very nature are breeding grounds for infection. In the past we’ve seen outbreaks such as influenza, tuberculosis, Norwalk and Group A Streptococcus.

COVID-19 is being added to that list, with more and more shelters across the country reporting outbreaks of the virus each week.

Within the homeless population are many seniors and a very high percentage of people with chronic illness and immune-compromising conditions — exactly those people COVID-19 hits the hardest.

Housing demonstration in Toronto on October 19, 2010. PHOTOGRAPH: CATHY CROWE

Researchers predict that when it comes to COVID-19, homeless people will be two to four times as likely to require critical care as the non-homeless population, and they will be two to three times as likely to die.

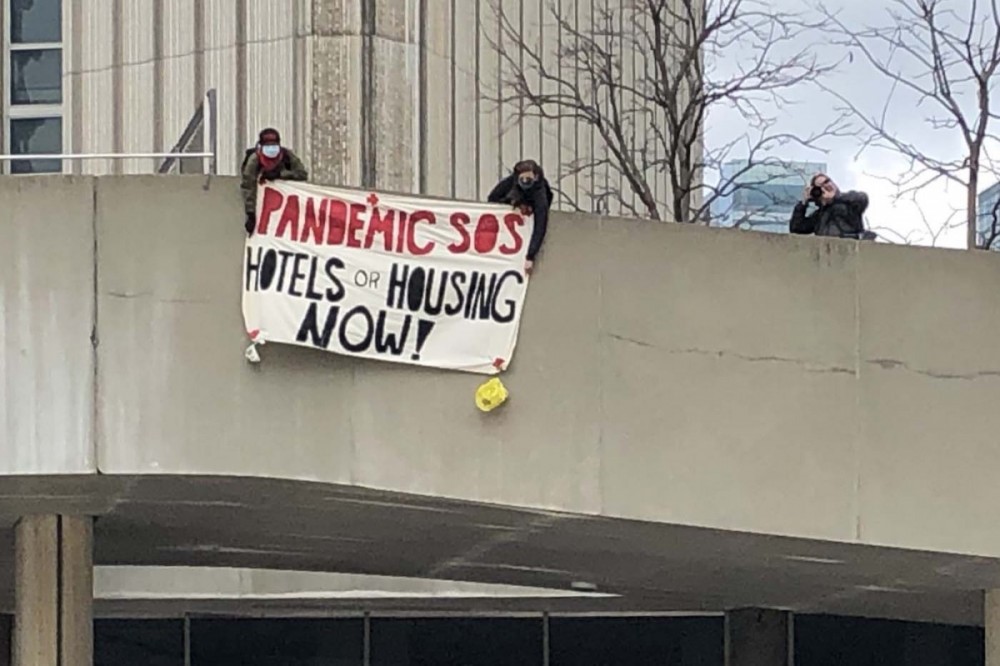

Around the world, cities have recognized the only prevention measure that will keep homeless people safer in a pandemic is "home," that is, to literally provide them with a room, either by fast-tracking people into housing or by sheltering them in hotels.

Hotels are mostly empty. They can be leased, expropriated or purchased depending on their size. Using them will keep hotel workers employed, homeless people safe and allow service agencies to continue providing their usual staffing support.

Canada has been sluggish to act. While several mid-size communities began using motels and hotels, cities like Calgary halted their initial attempts to use hotels, instead choosing to use a convention centre. Toronto led the way by promising to obtain hotel rooms or apartments with a goal of a room for every single homeless person, but their slow action belies that promise.

This pandemic is full of unknowns. How many tens of thousands of unemployed workers, facing a rent crisis, will become homeless? Will federal and provincial emergency packages be enough to protect people? Can this crisis spur enough collective action and the political will to finally build the housing we so desperately need?

Cathy Crowe is a long-time street nurse and housing advocate based in Toronto. She received the Order of Canada in 2018. Info on her memoir, A Knapsack Full of Dreams: Memoirs of a Street Nurse (FriesenPress 2019) can be found on her website. See an excerpt from her memoir in Our Times' Spring 2020 issue.