Prince George, British Columbia, 1991

The very first bush camp I planted trees out of was located on a flat, dry clearcut of 40,000 hectares (400 square kilometres) just east of Prince George.

Some clearcuts are covered only in “litter” (chipped wood and branches) but many are covered in deep “slash” — trees not good enough to be milled but which are cut down anyway to make way for machinery.

Clearcutting is done all over BC and Alberta — the two provinces I planted in — but most takes place on the backs of mountains so as not to disturb the public.

The pickup truck bringing us to camp from Prince George that day lurched off the highway and bumped down a dirt road at a steady clip. For a while the roadsides were a blur of dense evergreens. Eventually the trees gave way to the clearcut, and with the exception of bone-dry, sharp-edged slash piles lying constellated every 50 metres or so, it was flat brown landscape as far as the eye could see.

The truck let us out near the mess tent: a peak-roofed, white plastic shell fitted over a large collapsible frame. “Home Sweet Home,” James, the driver, said. He waved us towards the colourful village of planters’ tents pitched nearby on the dirt, but I could not stand the bleakness of the cut. I fled down a nearby embankment and set up my tent among leafy trees growing on an island of river rocks pushed up between two legs of a shallow river.

I was very pleased with that spot on the riverbed, but the following morning, the sound of the cook ringing the breakfast bell was drowned out by the sound of the river, and I slept in. James had to come down and get me. “You know the water might rise here,” he remarked while turning to go. But the water looked far down enough to me, so I didn’t move.

Up the embankment I scrambled after James. I dumped my gear outside the mess tent, then dashed down the line at the sandwich table, stuffing slivered vegetables and cheese in a bag. I got my gear in the back of James’ “FIST” (fibreglass insulated seedling transport truck) just as his and five similar trucks began kicking up dust and starting down the road.

“How come we don’t just plant here?” I asked the young college guy sitting next to me in the back of the crew cab as I did up my seatbelt. The guy had curly hair, a freckled nose and a fishing hat.

“We’ll do this last,” he said, “just before we decamp. We’ll plant right up to the mess tent, then take everything down and plant directly there. But the whole area won’t be fully planted for years.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“What you’re looking at” — he swept his hand casually at the miles of clearcut whizzing by — “is the Bowron Cut. Largest clearcut in the world. It’s a cut so big it’s visible from space.”

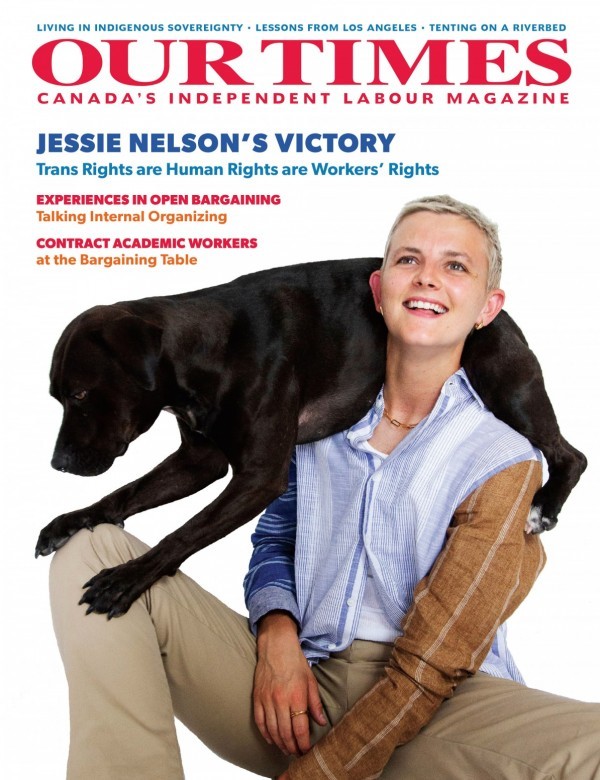

This story appears in the Summer 2022 issue. Head to ourtimes.ca/magazine to see what’s in the latest issue!

The cavalcade of boxy FISTs did a stint along the highway, then three trucks turned right and charged down a minimally marked road. We did not follow them. Instead, we drove the highway another 50 clicks before James veered right to start climbing a dirt logging road cut diagonally across the forested slope of a shallow mountain.

“Entering Forest Service Road 33: two pickups at zero clicks,” he said into the radio.

It was a protocol I would not understand until three weeks later when we turned onto a logging road and James discovered his radio wasn’t working.

He slowed down rapidly, pressed and pressed the red button on the handset.

No sound.

Logging roads are narrow and have no lanes, and this one wrapped around a treed mountain shoulder between a tall embankment and a steep drop.

It was while James was feeling around on the bench seat for his handheld that the logging truck with its 50-tonne load of logs careened around the corner.

James pulled onto the shoulder just in time. The logging truck flew past with the driver blasting his horn and looking furious as James gripped the steering wheel and gasped, looking 10 years older from fright.

On my first day of planting, though, the radio was working, and after 15 minutes of backroad driving, we came upon a circular clearcut running up and down the mountainside and bisected by the road.

These two slashy semicircles would hold 16 planters for two days, and about 50,000 seedlings.

“Two-metre spacing,” James announced while throwing waxed cartons of trees out the back of the FIST and onto the road. “Six trees per plot.”

The planters wasted little time. They stuffed their bags with trees, clipped the bags around their waists and, with their shovels, scrambled up the dirt embankments cascading down beside the road. They grabbed at large roots, using them to pull themselves up onto the matted surface of the clearcut.

James and I drove down farther and got out again. Behind us, Lisa, James’ girlfriend, was already halfway up the mountainside wrapping fluorescent ribbon like a garland on a high stick jutting off some slash. The ribbon marked the start of her piece and the end of the next person’s.

Tree planting is solemn work, but, like most work, it is best done lightly; and lightly is how Lisa draped the flagging as she stepped on a thigh-high piece of slash with her spiked boots and pushed herself up and over it to slam a seedling into the ground.

With the experienced planters’ work underway, it was time for my training. James put two bundles of 20 seedlings in his bags and instructed me to do the same. I followed his large rattling orange spiked boots up and onto the cut. There he strode purposefully to the centre of a large crater of exposed red dirt. The crater had a black-crust perimeter.

“This crater was formed when they burned a pile of slash. Every pile on this block will be control-burned by the logging outfit,” he said, pointing to the sharp and messy 15-foot pile of dried-out waste logs lying near us. “Exposed soil like this” — he pointed back at the ochre dirt — “is what we call ‘cream.’ It’s the easiest stuff to plant.” With his thin shovel blade James parted the soil like butter and shoved in a tree.

“The pocket here,” he continued, “the logs surrounding it offer a nice pattern of spots. Remember, all your trees have to be about two metres apart, and you need six trees per plot. A plot is a circle with a three-metre radius. When I look at this area” — he swept the tip of his shovel in the direction of the downed logs encircling us — “I see six obvious places for trees, mostly in the corners where the logs touch, or nearly. You should tuck the seedlings right up beside the slash because it protects them from snow and excess sun. Put the trees on the south side whenever possible.”

James took two steps towards the crater’s edge, plunged his shovel in, tilted it forward, then back, and reached in his side bag to pull out another tree.

“Hold the plug between your thumb and forefinger with the foliage shooting up past your wrist,” he instructed. “Bend down, slide the plug along the back of your blade until it’s tucked into one corner of the hole, then stand up and step the hole closed. Make sure the plug is covered and brush away any dirt from around the bottom needles. That way the tree won’t rot.”

James repeated this manoeuvre four more times in quick succession. “Put one here,” he said before taking two more steps and bending down again, “and here.” In this way James easily planted six spruce seedlings, and they stood straight, green and happy-looking along the burned edge of the crater.

“So that’s what you do. Remember to plant near obstacles, and as you plant one tree, look around for where you’ll put the next. But take your time today and keep correct spacing. It can take weeks or even months to start making money, so don’t worry about that.”

He left me as I began to plant seedlings in a lumpy little bulge of clearcut near the treeline. It was the quietest place I’d ever been.

Area by area I planted slowly as the sun came up and started cooking the ground. Soon I was right next to the forest. Fresh air, cooled between the treetops and the mossy undergrowth, poured out onto me. For a few moments I lingered there, gazing into the fathomless expanse of evergreens. But I couldn’t tarry for long. The trees in my bags were worth 19 cents each, and idling wouldn’t pay the bills. I turned my back on the forest to plunge more trees into the steaming ground of the clearcut.

We ate supper that night on the folding chairs and tables in the mess tent, and afterwards, Jerry, the supervisor, a tall, oldish guy with a big stomach, gave a talk involving news and instructions. “Don’t drink from the streams,” he said. “We got Giardia cases going.”

“What’s Giardia?” I whispered to a tidy-looking planter twisting his blond dreadlocks, sitting in the folding chair beside me.

“Beaver fever. Death by diarrhea.”

“Death?” I exclaimed.

“Not really,” he said. “But you can feel weak and sick for months. It’s very unpleasant. Make sure you don’t get it.”

After dinner, I talked with Jerry for a while out on the brown ground next to his camper. The sky above was cool, flat and overcast.

Jerry seemed nice. “How old are you?” he asked.

“Eighteen.”

“Well, whereas I’m old and stuck, seems like you could do anything.”

It was the nicest thing anyone had ever said to me. I spent the rest of the night in my tent, wondering about “anything.”

Two weeks passed quickly, and I’d had to correct many mistakes. I’d have one good day, then get bogged down in nose-high “schnarb” (deep slash) the next.

Sometimes I’d have to replant. But though I was still planting slowly, I began to make slightly more than minimum wage.

I was still tenting on the riverbed but never felt lonely, because, after driving back from the block each evening and eating supper, there were only about two hours left to occupy before bed. One night, James came down to my tent again. “Pascal and Eloise — those older Québécois planters — they want to speak to you.”

“Me? What for?”

“I’m not at liberty to say. They’re in the big brown canvas tent.”

I must be in trouble, I thought. Had I screwed up my spacing next to their lines? Had I “double-planted” or “creamed” them?

I came up out of the leafy creek bed and crossed the dirt to the French couple’s tent, pitched just beyond the mess tent.

I’d seen Pascal and Eloise at pre-works and meals but had never spoken to them. They were “highballers,” extreme production planters. Highballers usually kept a low profile and rested hard after work.

Unlike other planters, Eloise and Pascal didn’t spend money on bright outdoor gear or colourful Guatemalan clothes. Their outfits, white-person dreadlocks, boots and skin were a uniformly drab colour, possibly from the years spent kicking up dirt and absorbing it.

I found Pascal sitting cross-legged on some brown mats outside his tent, rolling Drum tobacco. “Sit down,” he said, offering me a spot across from him on a rag rug rolled out under the tent’s extended shade flap.

Just then Eloise came back from the shower with her head wrapped in a towel. She looked clean but still not great. She waved at us but went straight in through the front flaps of the canvas tent and disappeared.

Pascal had very little energy. “Sorry.” He gestured behind himself. “Eloise — she sick. We both sick. Fucking Giardia.”

Of course! They had Giardia. Everything about them was diarrhea-coloured.

“But that’s not why we ask you to come,” he said. “This contract is underpay. Trees like this should be 25 cent. But Jerry — he don’t listen. So tomorrow at breakfast we vote for strike. We ask you vote ‘yes’ for strike. Agree?”

“Hell, yeah.”

I didn’t have any idea what a fair tree price was, but striking seemed really quite thrilling.

The following morning, Jerry came into the mess tent in his usual good spirits. He collected his standard breakfast of five sausages, three eggs and 10 strips of bacon from the cook and sat down at the management table among his rolled-up topographic maps.

But just as he started eating, Pascal stood. “Jerry, we are tired of these low price, esti. The crew vote unanimous for strike. All work is stop until we get 30 cent for tree and 30 cent back pay for work of last two week.”

Jerry blushed and stood up. “I’m between a rock and a hard place here, you guys,” he said.

But Pascal was beaver-feverish and fed up. “No one plant until price go up, Jerry. So get out of hard place,” said Pascal, “and call Vancouver on the goddamn radio!”

Jerry called.

For that whole day, as we waited for Vancouver to decide, no planting was done. The Bowron Cut waited patiently for trees, and I sat by the shallow river, then played cards in the mess tent with some university kids.

There was no lunch or dinner prepared, but the cooks put out peanut butter, cheese, fruit and bread. A few times in the afternoon the sun broke gently through the cirrus clouds blanketing the sky.

At about five o’clock, Vancouver got back to Jerry on the radio. “I got 25 cents,” he announced in the dining tent. Another vote was held and the planters agreed to take the price. I felt somewhat bad for Jerry, who looked embarrassed from both sides; but Pascal looked like he felt bad for Jerry not one ounce.

Was it that night I woke up with water flowing through my tent and into my sleeping bag?

The creek rose in the darkness, and I had to evacuate to higher ground. Luckily my flashlight still worked, and I caught my boots and socks and journal and clothes before they floated away.

Cali Haan is a writer, ex-reporter and former tree planter. Her writings and artworks have won nominations and prizes, including Finalist, BC’s Funniest Female; and First Place, Vancouver Story Slam August 2021. She lives on a boat in Vancouver.