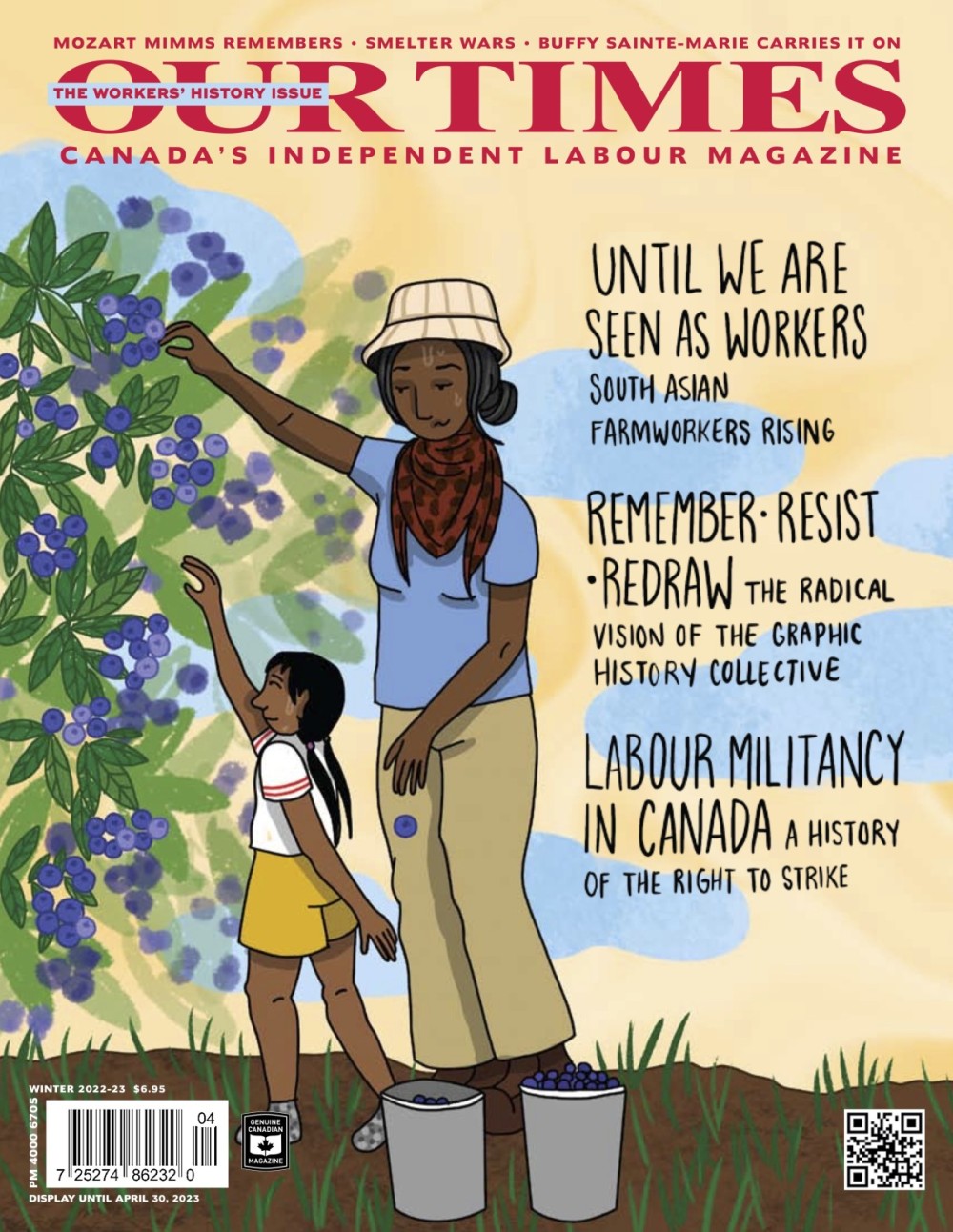

A partnership between the South Asian Studies Institute (University of the Fraser Valley) and the BC Labour Heritage Centre led to the groundbreaking Union Zindabad! South Asian Canadian Labour History in British Columbia. The book explores the stories of South Asian workers in BC over a period of more than 100 years, including the pivotal work of the Canadian Farmworkers Union (CFU).

For the book, labour historian Anushay Malik conducted a series of interviews. One of these was with activist Harji Sangra, who became involved in the Canadian Farmworkers Union in the 1980s when she was a university student. She taught English to women farmworkers and worked as an organizer for the union. Sangra also participated in writing and performing plays for the farmworkers’ movement, promoting the union and social justice issues.

Our thanks to the South Asian Studies Institute (University of the Fraser Valley) and the South Asian Canadian Legacy Project for allowing Our Times to condense and lightly edit the interview for publication in the Winter 2022-2023 issue.

ANUSHAY MALIK (AM): You're one of the few women who was involved in the Canadian Farmworkers Union. What were the inspiring factors that pushed you to do this? Were your parents involved in union work or political work before?

HARJI SANGRA (HS): My mom was a farmworker all her life. She immigrated in the late 1950s. And my dad, he always worked in a sawmill. He was always proud of the fact that he was in a unionized sawmill, which made a huge difference. He came in the early 1950s. Along with my mom, he always had stories of how well they worked — a lot of the South Asian men who worked in sawmills at that time. There was a lot of racism and discrimination. They did not get paid the same wages as Caucasian males. When they did become unionized with the IWA [International Woodworkers of America], that was a huge thing. So I always grew up with a union background.

AM: Can I ask you whereabouts your mom worked, and your dad as well?

HS: My parents lived in South Vancouver all their life. Most of the agricultural farms were in Richmond at that time. From 1970 on, my earliest memories are of my mom waking up at five a.m. She was a day labourer who picked cranberries for a huge, huge cranberry operation. My earliest memories were of driving my mom in the early morning to the farms over in Richmond with my dad, and then my dad dropping me at school, and my dad going to work.

My uncle, my mom's brother, and his wife, they were also farmworkers. We worked on the farms too. At about age eight or nine, during the summers, I would go with my mom, and we would be day labourers. We would pick blueberries. A lot of kids went sort of as something fun to do. We went because it was a necessity. My mom wanted me to pick berries with her, so we picked blueberries and strawberries every summer.

Children in the fields during strawberry harvesting, Fraser Valley, BC. Circa late-1970s. PHOTOGRAPH: CANADIAN FARMWORKERS UNION ARCHIVE, SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS LIBRARY.

I remember, it was really, really long hours, really tough work. But I also remember my mom having a lot of camaraderie with all the other Punjabi women. To this day, she still keeps in touch with all her friends.

My mom, after many, many years, was actually injured at work, at the farm. I still remember that there was no recourse. We spent years and years trying. And she had almost died. About five farmworkers were in a Jeep, on the farm, and there was a train coming and there were no proper markings [by the tracks]. And the Jeep went right over and these five women farmworkers, including my mom, were all taken to hospital with severe injuries. My mom had a head injury. She still has a big cross on her forehead to this day. After that, we tried to apply for disability benefits, and it was just an incredible nightmare. My mom was left with no income for a long, long time while we battled all the red tape to get her benefits. Those are certainly some of my early memories.

At that time, pesticides were quite big. When we were fighting our disability case, my mom was quite sick. She is quite sick now, too. She has a type of blood cancer. I always think back to the lack of protective gear and the pesticides being used. A lot of the women my mom's age, you know, did end up getting quite sick in their later ages.

AM: Did the other women who she worked with often come to your house?

HS: At that time, not many women drove. So my dad would pick up my mom's friends from all the way in Vancouver. I would be in the backseat, and my mom, my dad would drop them off. When I got my licence at 16, it was my duty to pick up my mom and her friends, and bring them back to Vancouver.

AM: Can you give us any insight into what the conversations between your mom and her friends were like?

HS: Oh, they would definitely complain about the conditions, in a somewhat humorous way. They were each other's best company. They would always say there was no proper bathroom. The owners had a lot of money, and the workers had to be very vigilant about their wages and not being paid on time.

There was always a sense of the weather. Women did weeding and gardening and blueberry picking, but the main thing was cranberry harvesting, and that is very laborious. It's very difficult, because you're wading in large trenches of water. Sometimes they would not have proper equipment. They would not have waterproof clothes. But there was definitely camaraderie.

This article is from our Winter 2022-2023 Workers’ History Issue. Head to ourtimes.ca/magazine to see what’s in the latest issue.

My dad would say to my mom, “don't work,” but my mom was illiterate. She can't read or write Punjabi. But she wanted to bring in an income, and those were the only jobs available at that time. There was a lot of exploitation, but there was also that “feudal” kind of sense [in relations with the employers].

Sometimes I tried to advocate on behalf of my mom, because we knew the farm owners. They weren't from our village, but they were people we knew, so there was always this sense of “you need to respect them.” And that we don't want to cross any limits. And that we don't want to say too much. You should just be thankful you have a job and they pay you.

AM: How did you then go about pursuing your studies and your career and becoming involved with the Canadian Farmworkers Union?

HS: It must have been 1983 or 1984. I was a UBC [University of British Columbia] student, in sociology. I was always interested in social justice. I was always interested in global issues. So I was always looking for opportunities, even when I was on campus, to be more involved in my community.

We come from a large extended family, and I always had lots of conversations with my cousins. We all grew up in humble situations. My grandfather came in 1907, so we were quite established, you know, but I was wanting to do more community work. I had a very good command of Punjabi — my grandparents lived with me, and that was a big focus. I was one of the few in my family at that time who had more language skills. I was quite proud of that.

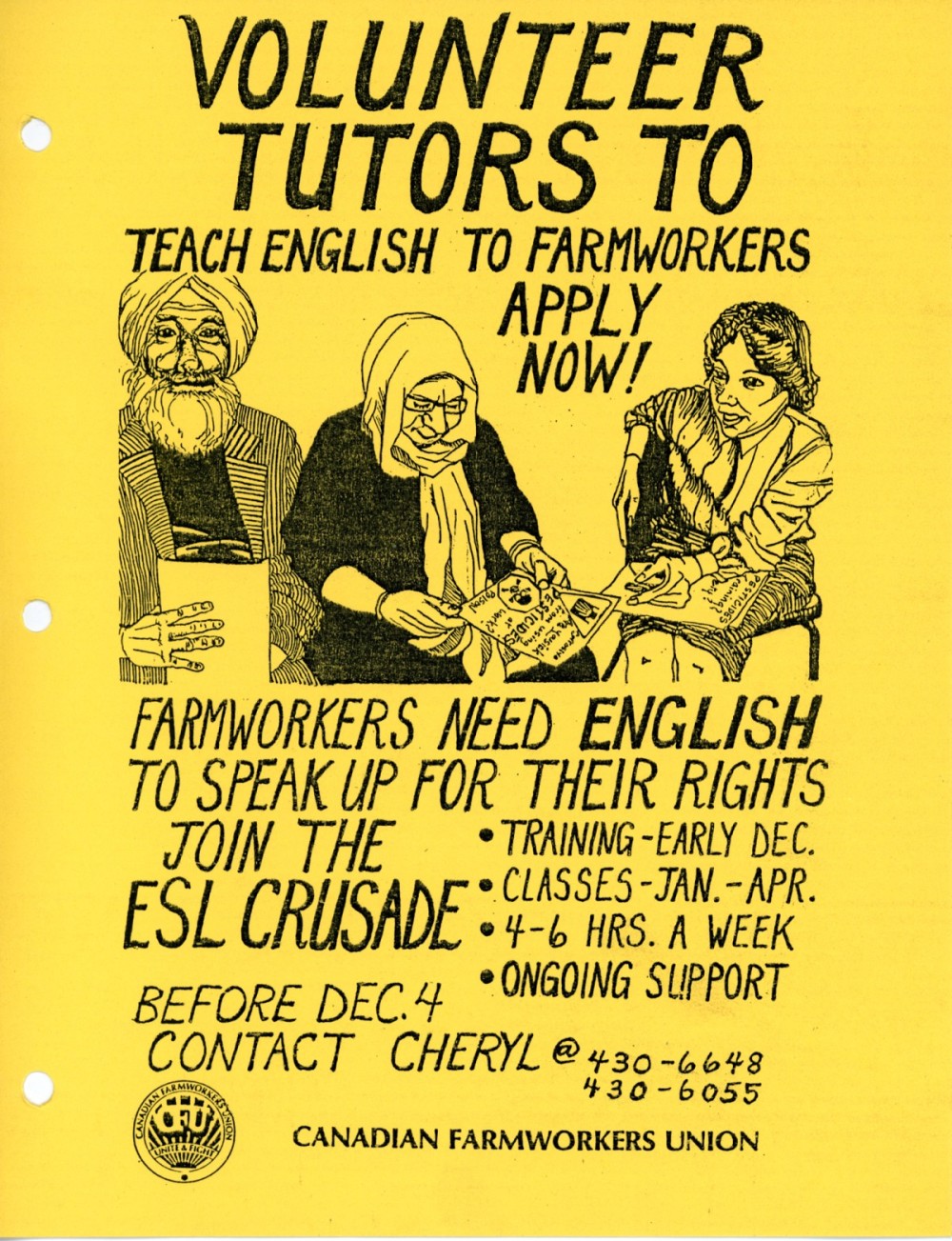

One day at UBC, in the South Asian centre, I saw a poster saying “teach English to foreign workers.” And I thought, wow, that would be really interesting. So I phoned, and that's how I was introduced to the Canadian Farmworkers Union. They had an office in Burnaby at that time. I went into the union office and met a great gentleman named David Jackson, who was an organizer [and ESL coordinator for CFU]. He was, I think, doing his master’s degree. He was the one, I think, organizing the program to teach survival, political English, to Punjabi farmworkers. It was just an incredible opportunity.

CANADIAN FARMWORKERS UNION ARCHIVE, SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS LIBRARY.

I would go to the office, and they had a big room at the back. And women would come. Very few women could come out to the union office at that time. So I would go to Punjabi women's houses. It was quite an interesting curriculum — everything from what are your rights to teaching English. It was based on the pedagogy of Paulo Freire. I found that fascinating, so I started reading more about it.

It was such a humbling experience because I connected with those women. I would just have so much fun. They'd offer me a cup of tea, and we'd always speak English. And we talked about how things were going on the farm, what kind of issues were happening and how they could deal with them.

That's where I met all the incredible people of the Canadian Farmworkers Union — Charan Gill, Raj Chouhan, Sarwan Boal. I was quite young at that time and just entering my studies. I just learned such an incredible amount. I was getting theory. I was reading a lot. David Jackson was awesome. And then I also had the practical, where I could just really connect with women, too.

Moving forward, I was hired one summer, under a grant, with the Canadian Farmworkers Union as an organizer. And that was incredible. I think it was two summers maybe. It really opened my eyes to what was happening in the industry. At that time, there were just so many tragic incidents. I still remember one of the incidents where a child had drowned in a bucket of water in a cabin. I just couldn't believe that could happen. I didn't really realize the situation of the cabins. A huge part of the farmworkers’ struggle was to improve the living conditions of people in the cabins. They had no running water.

AM: People have talked about the cabins before. Can you expand a little bit on this?

HS: It would be very basic housing. People would come from smaller communities up north to the Metro Vancouver area, and they would stay for the season and be given a room by the employers. Some or most employers took some money off the workers’ paycheques for that. And most of these cabins had no facilities. They were almost like slave conditions. One huge aspect of the Canadian Farmworkers Union was to improve the living conditions of the people who lived in the cabins. Many of them came with young children. They would come for the summer or the season with their families, and they would work under slave-like conditions for farmers.

AM: Can you describe what the organizing work involved?

HS: Well, me and a girlfriend were hired as organizers that summer. We just thought, “wow”!

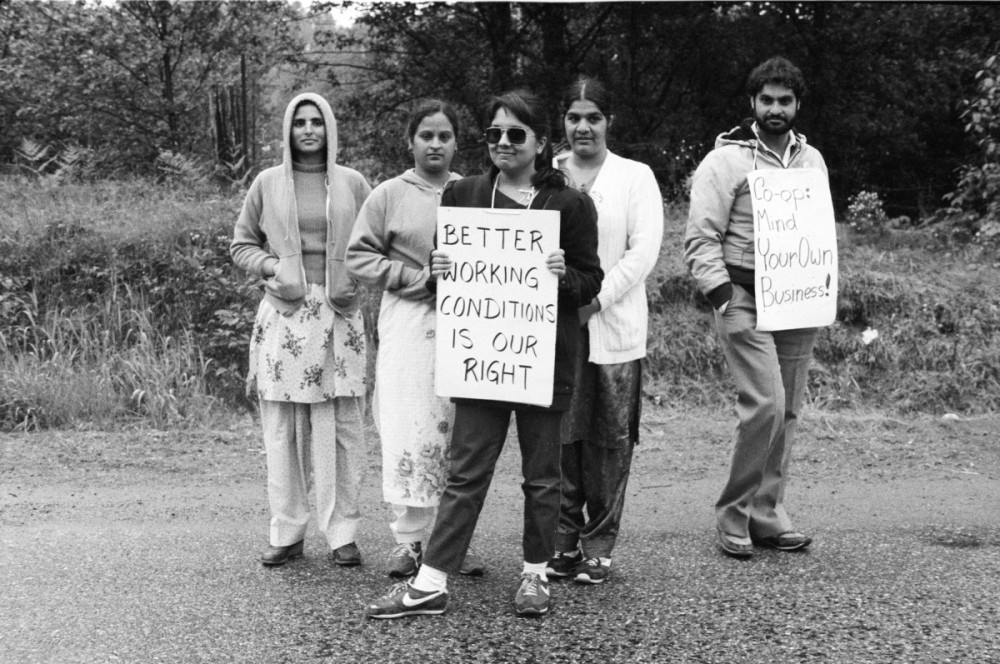

We had some training, and our job was to go to the fields. We would pose as berry pickers, and then we would talk to people. We would get a sense of what's going on. And we, in our own ways, very subtly tried to encourage them to join the union, explain the benefits of the union, make some personal contacts, leave some information. It was very interesting. One time [the farm owners] found out these girls are union workers, and we were literally chased off the farm.

AM: Were you ever scared?

HS: No, no, no — we had a right. We went, and we picked berries, and it's free speech. We could talk. People didn't talk openly, but I have memories of us picking berries, and I'm always quite a chatterer. It’s easy to start a conversation with some of the workers, and you'll get a sense of what's happening.

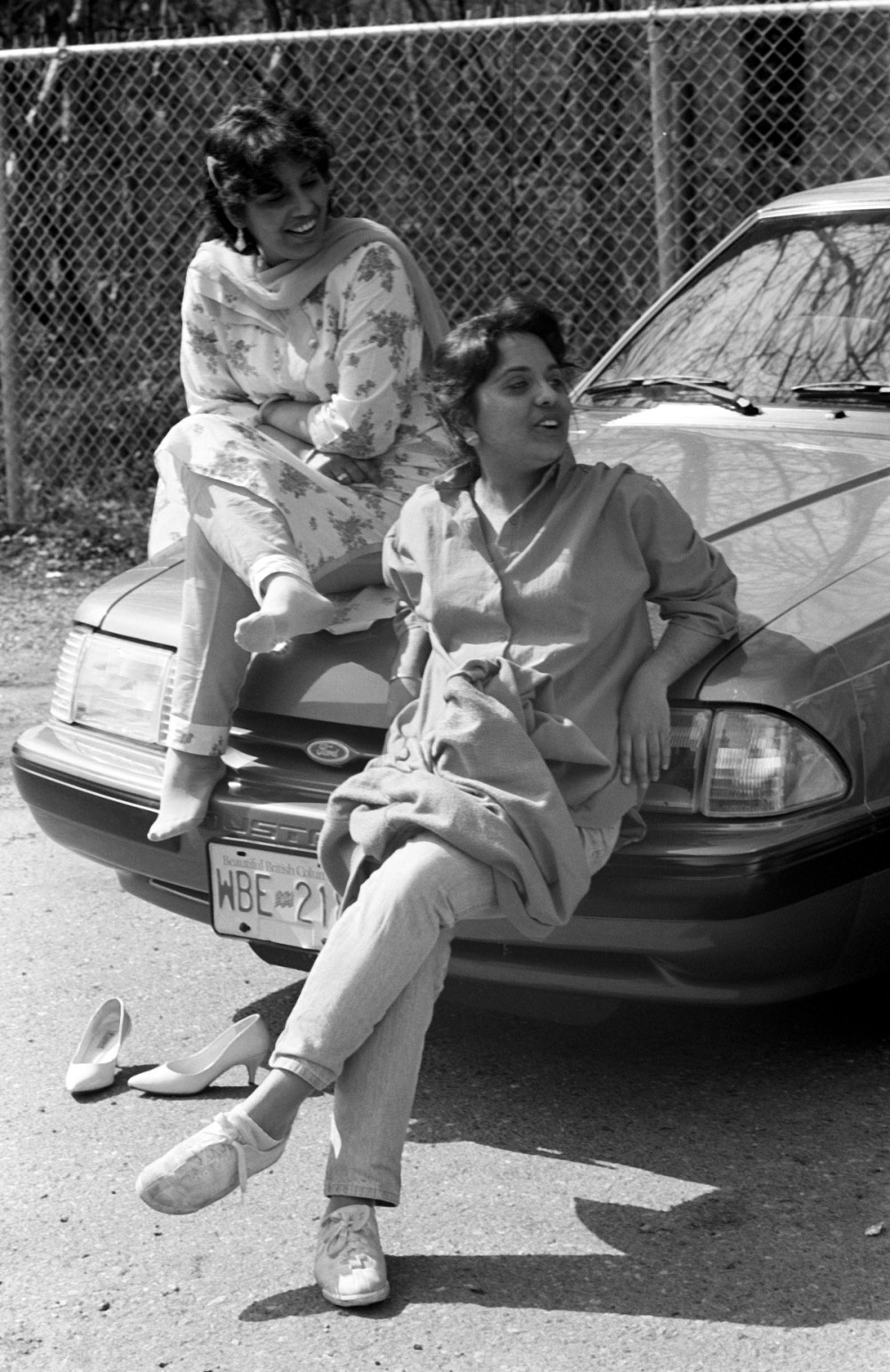

Harji Sangra (right) and Anju Hundal performed in Vancouver Sath’s theatre tour of the Fraser Valley. Vancouver Sath, a collective of South Asian writers, dancers, actors and union organizers, presented Punjabi and English theatre productions, including Picket Line, Crop of Poison and Whose Marriage?. PHOTOGRAPH: CRAIG BERGGOLD.

If people were very reluctant to talk to the union, it would, understandably, go in phases. If they knew we were union, word would get out. We wouldn't really say sometimes, but it was a mix. Even through my own family, I was really trying ways to raise awareness.

At that time, it was very much in the media here, too. There had been so many tragic incidents, so people were aware of what was happening with farmworkers.

I still remember, I was a little bit younger when Cesar Chavez came up from California. That was huge when he came up to give that solidarity. I remember the boycott of grapes in California. Chavez talked about that movement in California and how it was possible to organize farmworkers.

AM: Wow. And do you remember when you were speaking to these women — what were the one or two major issues that you heard repeated again and again?

HS: Well, one of the big things was it’s such hard, hard, labour-intensive work. It exhausted them. The really, really long hours. I even remember when we would go to the farms with my mom for the summers. You would go with contractors, right? Contractors were a big part of the whole industry. And we knew many contractors — some were family, relatives. Buses, they would pick you up at four o'clock, 4:30. My maternal aunt and uncle, they would be gone by four o'clock every single day. And they would come home at about 9 p.m. And that's just in my family. Those were vivid, vivid memories because we would go over and we would say, “Isn't Auntie back home yet? Isn't Mama back home?” And they would say, “Oh, no, no, it's summertime. They won't be back home ‘till about 9:30.” That was one huge thing. The other one was the infrequency of proper payment. There were a lot of issues around payment. In terms of employment benefits, there was a lot of abuse around that — part of your pay being cut.

AM: With all this work, I mean, you're also then friends and close with people like [union activist] Pritam Kaur, which I'd love to hear a little bit more about, by the way. But I just want to know how the transition toward Vancouver Sath* happened, not just necessarily Vancouver Sath, but also where the women are. I mean, what your story is enabling us to see is women.

HS: Well, there was a huge strike at Hoss Farm. And Craig [CFU photographer Craig Berggold] did a lot of photography, a lot of documentation of that strike. That was huge. That was such an historic strike. That was all led by women on the mushroom farm. I forget some of the names, but the picket line around Hoss Farm went for ages and ages, and it was all women who had been fired because they had organized and unionized who were at the front of that picket line.

From organizer to actor: Harji Sangra (centre), performed in Vancouver Sath’s play Picket Line at the 1987 Vancouver Mayworks Festival in Grandview Park. The play tells the story of the CFU’s organizing drive at Hoss Mushroom Farm. PHOTOGRAPH: CRAIG BERGGOLD.

That picket line was there for a long time. And I remember I went to that picket line, and I met a few people there at that time through the union.

[Members of Vancouver Sath] Sukhwant Hundal, Sadhu Binning, Jagdish Binning, Anju Hundal — they were all part of that. When the strike was happening, everybody would go to the picket line to support these women. So that’s where I got to know Sadhu and Vancouver Sath a little bit more. And we became really good friends.

And I was really, really inspired by the work of Vancouver Sath at that time. They had been publishing a magazine called Watan [a quarterly dedicated to Punjabi language, literature and culture in Canada]. And from there, they made Vancouver Sath. And then I was part of that.

It was like family, and it was like mentors, and it was people I learned so much from about social justice, about community work, and about Punjabi. And I remember still, at that time, I think they said, “I heard you were going to write a play, and we want you to be in it, in Punjabi.” And I said, “No, no, no! I can't do a play. But I'm interested in all these topics.”

They encouraged me, and that's where I really developed my Punjabi skills even further. And I really enjoyed it. We would cooperatively write plays, and then we would perform them. And it was people's theatre — based on the concepts of community theatre, power-play theatre. And it was just incredible.

We did so many plays in the community. And one of the plays, of course, was called Picket Line.

Dr. Anushay Malik is a labour historian and Visiting Faculty for History and Labour Studies at Simon Fraser University.

Vancouver Sath was a group started by politically conscious Punjabi artists, writers, other creators and community activists. Along with their many endeavours, they wrote and performed plays. Some of the group’s members were actively involved in the BC farmworkers’ struggle. To read more about Vancouver Sath, see rungh.org/vancouver-sath.

For more about the South Asian Studies Institute, see ufv.ca/sasi.