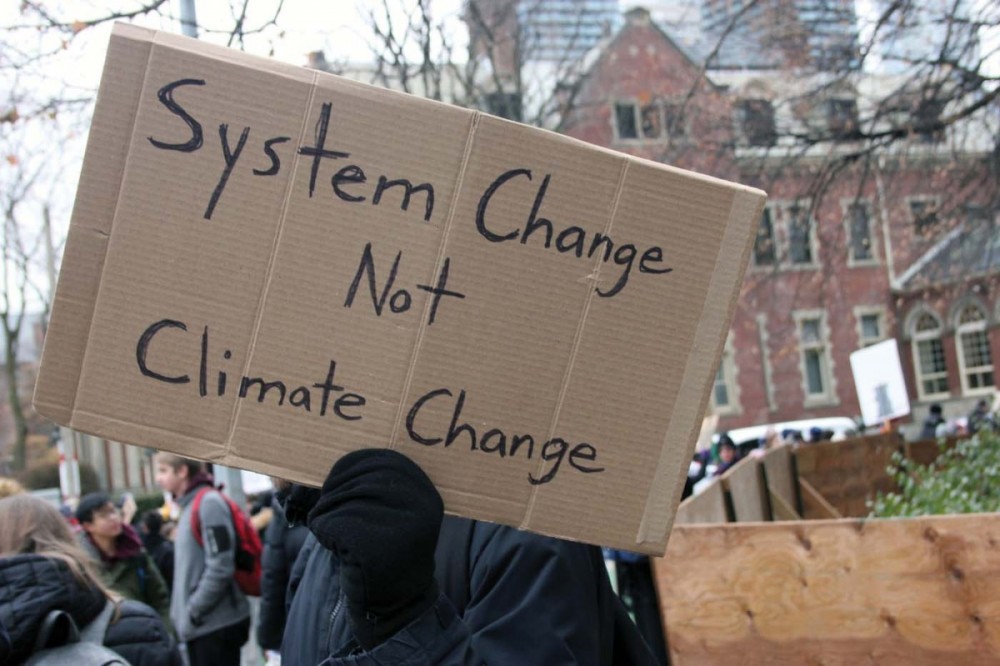

One of the largest acts of civil disobedience in Canada’s history took place just weeks before the 2019 federal election, sending an unequivocal message to politicians of all parties that people want action on climate change now. A network of young people, students, activists, and allies had already formed Climate Strike Canada earlier in the year, inspired by Swedish protester Greta Thunberg and youth around the world who began striking from school one day each week as part of the “Fridays for Future” movement. Climate Strike Canada includes in its mission the rights of Indigenous peoples and migrants, workers’ rights and economic justice, and anti-racism and social justice. “Each battle is entangled within another,” reads the organization’s mission statement.

On September 27, its members joined forces with other concerned citizens and groups across the country to protest in solidarity with that day’s global environmental action, #EarthStrike, drawing attention to the urgent need to stop the acceleration of global warming. Indigenous youth marched at the front of Montreal’s climate strike. Autumn Peltier, from the Wikwemikong First Nation on Manitoulin Island in Ontario, brought the message to New York City and addressed the United Nations just a few days later.

In 2018, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) documented that a maximum 1.5 degree Celsius rise in temperature is a hard threshold we cannot cross. There is nothing abstract about the ecological evidence around us: The IPCC has stated that CO2 emissions must be halved within a decade to prevent irreversible catastrophe. As Thunberg has famously said, “our house is on fire,” fuelled by the past century’s consumption patterns.

Tiffany Balducci, president of the Durham Region Labour Council in Ontario, is aware that change must happen on a scale that exceeds the personal, but includes the local. The organizer is heavily involved in the battle to reverse the climate emergency. Her activism, she explains, started in Flint, Michigan, where she spent her younger years.

Tiffany Balducci, president of the Durham Region Labour Council, in Ontario, has helped devise a strategy that simultaneously addresses the climate emergency and the loss of GM as a major employer in Oshawa. PHOTOGRAPH: RYAN PFEIFFER/TORSTAR

“I always say I found my American dream by moving to Canada,” quips Balducci. “Partly that’s been about finding an amazing, unionized job in the public services, but what I saw happen in Flint and Detroit, I just didn’t want to see that happen in Canada. It’s not perfect, obviously. There’s a lot of work to be done. But I thought, ‘Let’s not let that happen here’.”

The two Michigan cities are often held up as symbols of urban decay and the social malaise that accompanies losing a major employer. While General Motors is still headquartered in Detroit, the automotive manufacturer filed for bankruptcy protection in 2009 and subsequently restructured, closing over a dozen U.S. and Canadian manufacturing plants and accepting tens of billions in financial aid from the U.S. and Canadian governments. GM was founded in Flint, a city hit hard as the company eliminated tens of thousands of jobs over the last four decades. The population, and municipal services (ranging from public schools to water treatment facilities), collapsed in Flint and Detroit; meanwhile, political corruption and crime rates soared.

Balducci represents the first in four generations of her family to have never worked for GM, even as a summer student. She worked as a librarian in Oshawa after moving to Canada and currently works with the University of Toronto Education Workers Union (CUPE Local 3902), on full-time release with CUPE Ontario as a member organizer with the Communities Not Cuts campaign. But with so many friends and relatives who worked for the automotive manufacturer, either in Michigan or Ontario, the labour council president is attuned to their struggles. In conjunction with the Green Jobs Oshawa group, which she described as “a coalition of workers, youth Climate Strike organizers, community leaders, environmentalists, labour and social justice advocates,” Balducci has helped devise a strategy to simultaneously address the loss of GM as a major employer, and the climate emergency: “We’re all working towards the common goal of placing the plant in Oshawa under public ownership, in order to repurpose it for socially beneficial manufacturing, like electric vehicles.”

Welcome to the Green New Deal, Oshawa-style — an idea with American origins, making inroads north of the border. Activists throughout Canada have also drawn tremendous inspiration from Quebec’s Pact for Transition (Le pacte pour la Transition), a pledge to mobilize, both individually and in groups, for climate action. To date, over 285,000 people, and counting, have signed. Another motivation for climate activism has been the Leap Manifesto, which was created in Toronto in 2015 by 60 representatives from Indigenous, labour, environmental, and other groups linking human rights and ecological justice. The Leap petition has evolved through input from subsequent contributors and drawn 52,584 signatures from people pledging to follow its lead, “A Call for a Canada Based on Caring for the Earth and One Another,” which originated in Naomi Klein’s 2014 book This Changes Everything.

PHOTOGRAPH: LORRAINE ENDICOTT

In the U.S. the “New Deal” was rolled out by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to boost good jobs and create public infrastructure during the Great Depression; Naomi Klein’s latest book, On Fire: The Burning Case for a Green New Deal (2019), summarizes some of what it accomplished:

“During the New Deal decade, more than 10 million people were directly employed by the government; most of rural America got electricity for the first time; hundreds of thousands of new buildings and structures were built; 2.3 billion trees were planted; 800 new state parks were developed; and hundreds of thousands of public works of art were created.”

The American and Canadian Green New Deals have not originated from either country’s leader, but from voices critical of the Republican and Liberal parties’ common ground: inaction on the climate emergency. In February 2019, Democratic Congresswoman Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey submitted their “Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal” legislative proposal to the U.S. Senate, laying out a 10-year plan working toward “net zero” greenhouse gas emissions, plus renewed investment in public infrastructure projects. It was voted down without discussion a month later, although it has since served to motivate some Democratic leadership candidates and also activists in other countries, including Canada.

Balducci is one of those activists. Also a vice-president of CUPE Ontario and vice-president (labour councils) at the Ontario Federation of Labour, she sees unions as a perfect catalyst for helping advance the movement in Oshawa and elsewhere. “We’re already really good organizers, so if we could organize around climate justice, use our skills in that way, and help create fair, unionized jobs, it just makes sense,” she explains. While her earliest awakening to ecological concern involved her becoming a vegetarian, she realized that individual action was not enough. Balducci says that the Green Jobs Oshawa group has empowered its diverse members through collective action towards a specific, attainable goal:

“We actually raised money for funding a feasibility study, so instead of just speaking about what could be possible, we actually had an engineer research what is feasible, the material that we currently have, how much it would cost, all the stuff like that. So there’s a tangible plan there. It’s almost criminal, in my mind, not to give it a shot. The answers are right in front of us, the way to make the Green New Deal a tangible thing in Canada. We always say we can make Oshawa the engine of the Green New Deal!”

But is political will and timing on the side of a Green New Deal for Canada? As Patricia Chong, an Asian Canadian Labour Alliance member and co-facilitator of “Green is Not White” environmental workshops, notes: “It depends on what Green New Deal vision we are talking about.”

Labour educator Patricia Chong notes that wherever elected representatives do not embrace a Green New Deal, the labour movement offers opportunities to collaborate on concrete plans for workers and the planet. PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY PATRICIA CHONG

Chong observes that the federal government’s ability to pass legislation supporting any version of the plan was unclear. “As a minority government, the Liberals need the support or some combination of support from the NDP, Bloc Québécois, Conservatives, the Green Party, and/or now Independent Jody Wilson-Raybould to avoid a no-confidence vote,” she points out. “Given their lacklustre support on climate initiatives in their first term, the Liberals must be pushed hard to put forward the needed initiatives to combat climate change with an environmental justice focus.”

The Liberals’ minority government status is, at least in part, the result of Alberta and Saskatchewan voters fearing an economic downturn and job losses resulting from even moderate proposals to address climate change.

In Quebec, public sentiment at the polls confirmed a different view: The Liberals were not doing enough for the environment. The Bloc Québécois more than tripled their seats (from 10 to 32) in the October election, narrowly second to the Liberals in that province; party leader Yves-François Blanchet’s successful platform focused more on keeping oil pipelines from crossing Quebec than traditional themes of separatism. There is broad commitment within Quebec to “just energy transition,” based on clean electric power driving the Quebec economy and on selling that power to the U.S. or to Ontario. According to John Cartwright, of the Toronto & York Region Labour Council, the Quebec Federation of Labour (FTQ) has been instrumental in bringing together the province’s main business council, farmers, co-ops and Indigenous leaders, among others, to address the climate crisis.

PHOTOGRAPH: LORRAINE ENDICOTT

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau named Jonathan Wilkinson minister of environment and climate change in November; the National Union of Public and General Employees (NUPGE) sent the former fisheries minister a letter shortly thereafter, strongly recommending that Wilkinson prioritize just transition. The Saskatchewan-born minister has publicly stated that his objective is “a long-term transition strategy that will get us to net zero [CO2 emissions].” In the short term, he has voiced continued federal support for the controversial Trans Mountain pipeline, designed to transport Alberta crude oil to markets outside the province. Jobs are again pitted against the environment, at least for the moment.

Wilkinson replaces Catherine McKenna, who was re-elected in October, but reassigned to a new portfolio (infrastructure and communities). In her time as environment and climate change minister, McKenna was frequently subjected to online and verbal attacks; her 2019 campaign office was vandalized with misogynistic graffiti. As Naomi Klein has identified, conservative white men have a record of turning to sexism, racism, and other forms of injustice to defend their affluence; nowhere is this more pronounced than in current debates about climate justice: “One of the most interesting findings in studies on climate perceptions is the clear connection between a refusal to accept the science of climate change, and social and economic privilege.”

No Jobs on a Dead Planet

A Green New Deal cannot privilege workers based on unfair criteria like race, nationality, sex, or class. “We always say that there are no jobs on a dead planet,” says Tiffany Balducci, directly clarifying why ecological considerations can no longer be separated from concerns about employment. When corporations and governments are primarily tasked with reinforcing the capitalist status quo, they benefit a small fraction of people worldwide, at the expense of workers and ecosystems. A Green New Deal must be radical enough to reject this model of “business as usual” and invite input from marginalized groups.

The Liberals must be pushed hard “to put forward the needed initiatives to combat climate change with an environmental justice focus,” says Patricia Chong. PHOTOGRAPH: LORRAINE ENDICOTT

Patricia Chong cautions against assuming that the current movement for climate justice automatically speaks for marginalized communities. A labour educator at AMAPCEO (The Association of Management, Administrative and Professional Crown Employees of Ontario), Chong is also a Unifor 591-G shop steward. “There is nothing inherent in the Green New Deal that addresses the structural inequities that underpin our capitalist economy,” she notes. “Even the reference to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ of the 1930s prioritizes an economic stimulus approach, and the New Deal has been criticized for largely benefitting white people at the expense of Indigenous and racialized communities. I say this while recognizing that supporters of the Green New Deal are pushing for it to include principles that include Indigenous self-determination, social justice, equity, human rights, workers’ rights, etc.” If a Green New Deal is to fulfill its dual mandate (i.e. dramatically slowing the rate of climate change while creating decent employment in sustainable industries), these considerations cannot be a mere afterthought.

Facilitators at a Hamilton, Ontario, “Green is Not White” workshop. PHOTOGRAPH: COURTESY CHRISTOPHER WILSON

The workshops Chong co-facilitates are called “Green is Not White” for a frustrating reason: in the past, environmental activism has usually been limited to people from privileged demographic strata. “Then add to this situation that while racialized and Indigenous communities disproportionately suffer from the impact of climate change, they are marginalized by the ‘professional’ environmental movement that continues to be overwhelmingly white,” she explains.

Balducci says that Green New Deal discussions have seen business-oriented unions oppose the social justice unionism of others. “Of course, when you talk about the broader labour movement and unions, I think that some difficulties in having climate justice-organizing conversations that I’ve come across is the fact that unions and workers have been oppressed through downward pressure on working conditions and benefits and pensions,” she explains. “We’re always in protection mode, so it’s a barrier to creating what a Green New Deal could look like, throughout a transition period and beyond. Because it’s really hard to embrace a vision, and a different way of working, and maybe a different economy, when you’re in survival mode. That’s the whole point: If you’re stuck on a hamster wheel, you can’t even envision what it would look like.”

So what would it look like?

Something Drastically Different

“I think what we’re seeing is, people are ready for something drastically different, a different type of politics, a different type of world than we’re used to,” responds Balducci. “But we see this sometimes where people are voting right-wing, [because] they're having economic anxieties. Instead of embracing the idea of change, of anti-capitalism, they’re embracing the right wing because it seems like a quick fix.” She adds that meaningful change will never happen if the conservative strategy of “leaving it up to the free market alone” is not challenged, and now.

Many good jobs of the future will emerge in zero-carbon public housing and environmentally viable mass transit, notes the CUPE Ontario vice-president. “I think people critique the Green New Deal for being vague and not really tangible. That’s the other reason why I like the organizing that we’re doing in Oshawa [around repurposing the idled GM plant],” she continues. Clinging to conservative values in order to preserve jobs cannot help workers or the planet in the long run, but unions are uniquely positioned to protect workers struggling to find their place in the rapidly changing employment landscape.

“Unions need to realize that we’re already experts in dealing with layoffs and retraining,” says Balducci. “We do it all the time when people lose their jobs. We can provide one-to-one support in these transitions, in addition to government support, so unions can be very beneficial in this transition to good jobs and a Green New Deal.”

Defining the Green New Deal for Canada starts at the individual and community level. At “Green is Not White” sessions, Chong helps people commonly excluded from meaningful dialogue about climate justice find their visions and voices: “The sense I get from the facilitators and participants is that there is a strong demand for change, but people often feel that they don’t know where to start. Thus, we end the one-day workshop asking: How can we as racialized, Indigenous peoples, and/or allies take action in our communities, workplaces, and unions to build environmental justice? What are our goals? What tools, resources, and allies exist?”

The Asian Canadian Labour Alliance member observes that in Canada, unions have been more active in envisioning a carbon-neutral future than their American counterparts. “The Canadian Green New Deal involved the labour movement early on — perhaps learning from the mistakes in the USA where the AFL-CIO [American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations] came out against the Green New Deal?” she muses. “Unifor supports the Green New Deal framework and is pushing for retraining, buy-outs, investment in clean-up projects, transition projects, green projects, [and more], so workers [can] have meaningful work.” Other supportive unions include ATU Canada (the Amalgamated Transit Union) and the BCTF (British Columbia Teachers’ Federation). CUPW (Canadian Union of Postal Workers) and CUPE Ontario are examples of unions that have endorsed the deal. [Editor's Note: If your union has endorsed the Green New Deal for Canada, let Our Times know!]

Balducci says she is a New Democratic Party member, and she wishes NDP leader Jagmeet Singh had been more outspoken on addressing climate change during the 2019 election campaign. “Our expectations may be tempered by the federal election, but I think that people aren’t giving up,” she tells Our Times. “In order to get the political will there, no matter who is elected, it will take huge organizing amongst all of us to pressure whoever’s in office, because we have no choice. I think people are realizing that. It’s becoming more popular to embrace the idea of the Green New Deal. I think people understand that it needs to happen.”

“People are ready for something drastically different, a different type of politics, a different type of world than we’re used to,” says Tiffany Balducci. PHOTOGRAPH: ELIZABETH LITTLEJOHN

Which kind of Green New Deal will Canadians ultimately choose? Chong explains the two main formulations: “If the climate crisis is defined as a problem where we need to move money from greenhouse-gas producing industries to non-GHG producing industry, then the answer is to move the money around. If the climate crisis is defined more broadly as a problem that also includes environmental racism, Indigenous genocide, and capitalism, then the solution is also going to be very different.” Her decision is clear: “When we talk about a Green economy, we do not want to replicate the inherent inequities we already have.”

Chong notes that Green is Not White workshops have thus far been conducted in Ontario; she’s curious about how they would be received in other parts of the country, particularly Quebec and the Prairie provinces. She adds that in places where elected representatives do not embrace a Green New Deal, or actively oppose the logic behind it, the labour movement offers opportunities to collaborate on concrete plans for workers and the planet: “It is important to have a sense of solidarity so individuals can join with existing organizations and campaigns rather than feel isolated and alone.”

In Oshawa, a template is emerging. Balducci says that there is popular support for getting the GM plant producing electric vehicles, which would be used as part of the country’s largest corporate vehicle fleet, belonging to Canada Post, to start. North American manufacturing jobs have been in decline for decades, hurt by the economic underpinnings also known to fuel environmental destruction. A Green New Deal can power a comeback for underrepresented people and ecosystems, without making good jobs casualties along the way. “It’s all totally possible, but we can rely on an existing social safety net infrastructure to support workers who may be out of work, especially due to the climate emergency,” she stresses. “We have to look at where the safety net is already failing workers and needs improvement. So what people refer to as ‘just transition’ is not only about helping workers find new employment, but, in my opinion, can lead to a complete economic transformation, employing basically the social welfare state, for lack of a better term. The government has to step in and retrain individuals and provide jobs, just like what happened with the [original] New Deal in the States.”

The Moment Has Arrived

The 2019 federal election produced results that showed ambivalence about a Green New Deal for Canada, undoubtedly due to fears about what it could mean for the economy as we now know it. As Naomi Klein states in her latest book, these fears are justified: “Climate change detonates the ideological scaffolding on which contemporary conservatism rests.” What replaces the “ideological scaffolding” is unclear, and perhaps beyond the scope of party politics. For organized labour, the moment has arrived to transform fears into a future authored by its participants. Balducci phrases it well, in reference to Green Jobs Oshawa, but also the bigger picture: “For this to happen, we’re going to have to throw capitalism under the bus — but it will be an electric bus!”

* * * * *

PHOTOGRAPH: LORRAINE ENDICOTT

BC Bill for Green New Deal

On December 5, 2019, NDP Finance Critic Peter Julian, the MP for New Westminster-Burnaby in BC, re-submitted his Private Member’s Motion M-1 on a Green New Deal for Canada.

M-1 calls on the House of Commons to take the position that it is the “duty of the government to create a Green New Deal.”

The motion defines a Green New Deal as a 10-year national mobilization to:

• reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions

• create millions of secure jobs

• invest in sustainable infrastructure and industry

• promote justice and equity for Indigenous peoples and all “frontline and vulnerable communities.”

Visit our-time.ca to read more about the above, and to find out how to support the motion. Though we're not related to the youth-run climate organization, we do like their name and we share a common goal — to tackle climate change in our time(s)!

Editor's note: The above article refers to AMAPCEO by its full legal name. AMAPCEO now represents a broad range of professional and supervisory employees in the public sector, and goes by the somewhat simpler name ‘AMAPCEO.’ While AMAPCEO represents team leads and project managers, the union does not represent management.

Melissa Keith is a former radio broadcaster and an award-winning freelance journalist. She lives in Lower Sackville, Nova Scotia.