Ducks, a graphic novel, has found a literary audience. It won CBC’s 2023 Canada Reads competition and, among other accolades, was named a New York Times notable book of 2022, one of The New Yorker’s best books of the year, and one of The Globe and Mail’s top 100. I hope it is also being read by us. People who work these kinds of jobs, in these kinds of places. I hope that we workers can start to look at our lives with a bit more nuance and complexity. I hope we can stop these simplistic narratives that pit jobs against the environment, trades education against university, job security for men against women's rights, fighting for better conditions where you live against migrating elsewhere to work.

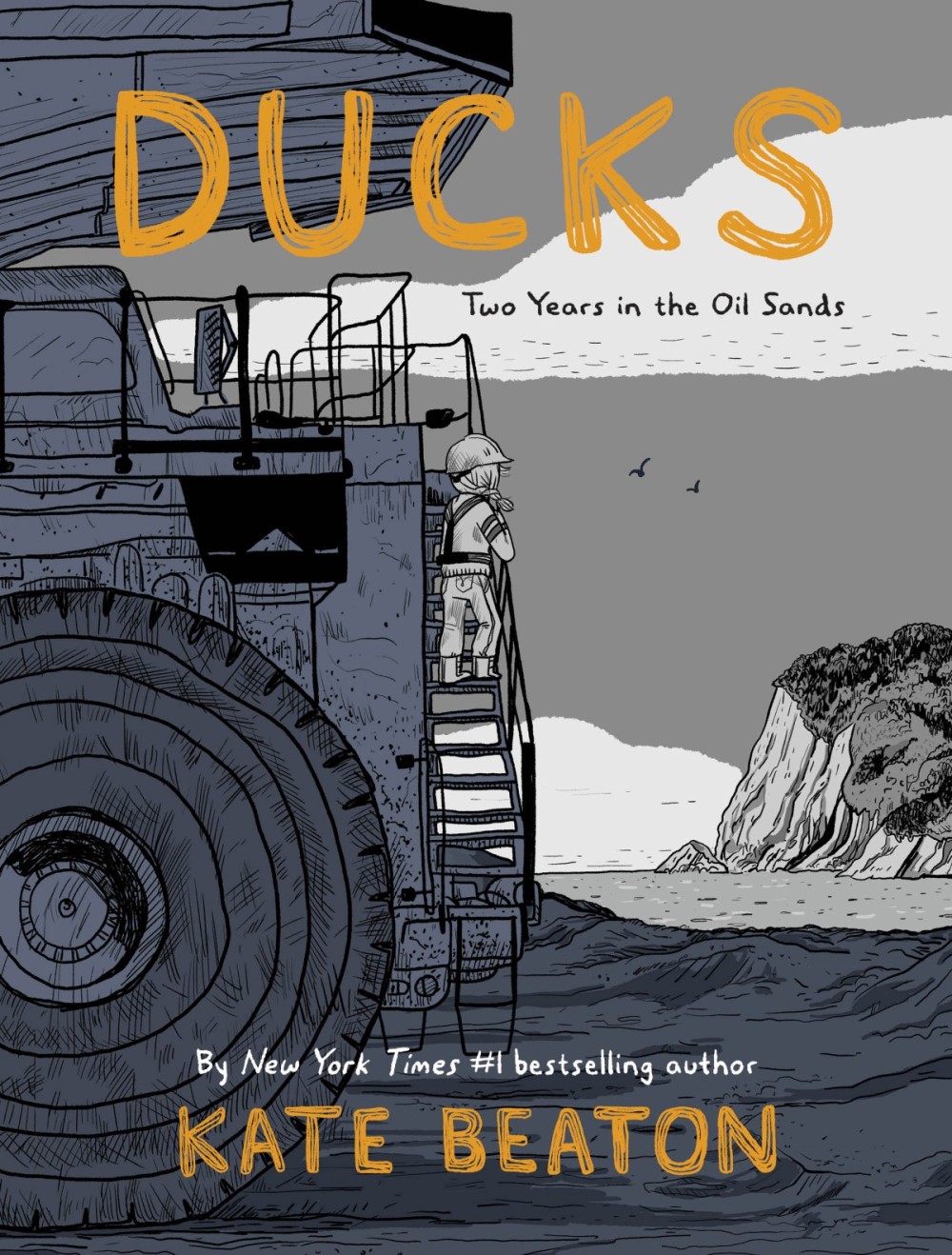

In Ducks, the main narrative unfolds in devastatingly simple comic storytelling form periodically interrupted by panoramic drawings of various work camps and mine installations, all in grim greyscale that reinforces the harsh realities depicted by the story. Beaton often references the traditional way that east coast working-class Canadian stories have been told, not in capital “L” “Literature,” but in folk music. Several East Coast folk songs make an appearance in Ducks, harnessing a Gaelic and Acadian musical storytelling heritage that is shown as a major artistic outlet, and a way for displaced people to make sense of their lives in a world where a plastic plant is a major aesthetic upgrade.

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands. By Kate Beaton. Drawn & Quarterly, 2022. 436 pages. $39.95. ISBN: 9781770462892. eBook ISBN: 9781770466531.

A lot of people who read Ducks will be taking a tour into an unknown corner of Canadian work life. Not me. My work life has looked a lot like Kate Beaton's experiences in the tar sands. I'm not from Cape Breton, but my family is. I also went into debt for a degree in history and anthropology, and paid a price for that degree in other ways as well.

Like Beaton, when I was young, in the early 2000s, I went away from my home and family — she to the tar sands, I to the army, another traditional maritime escape hatch. I also dealt with being a young woman in a hostile place, a place that for men is also pretty grim, but where I had to deal with the additional problems of them (men).

Now I'm not so young, and I work as a construction electrician, and I don't know that I will ever get out. Beaton's book makes me feel all of this. Maybe I'm too close to it.

I don't know what it will make you feel, but I know it will make you feel something.

As a woman in the trades, I feel pressured to either be empowered by my work, or horribly oppressed by it. These narratives leave me no room to talk, with nuance and complexity, about what the experience is actually like, to tell the kind of story that Kate Beaton managed to tell. She draws what it’s like to work in an extremely male-dominated space. To deal with lip-service safety. To be housed in a way that makes it nearly impossible to protect yourself against sexual assault. To then be told that women have it so easy, that you could report any man and ruin their career, that to be a woman is a career advantage, while living a reality that is the exact opposite. While also dealing with non-gendered problems of work — driving exhausted down snowy highways, being exposed to toxic chemicals, doing heavy labour. Sleepwalking at night so you never rest. The complexities of work — the surprising moments of solidarity and betrayal by both men and the very few other women.

For us in the union movement, it is important to be able to look at the realities of our working life, and not be sidelined by either cheerleading optimism or the kind of cynicism that makes you give up. What does our work actually look like? What does it feel like? How are people's experiences different? This is the kind of story a book like this tells.

For Beaton, another type of job is simply a different flavour of exploitation. She finds work in Victoria, BC, ironically at a maritime museum — the kind of job she trained for in university. She can wear cute skirts, and bike to work, and live in a place that is beautiful. She meets people who encourage her comic art. But the job does not pay enough to live on. She is still saddled with student debt, lives in one room with just a mattress on the floor, and struggles with trauma from her time in the oil sands. She cannot even start to pay her loans, because the very career those loans paid for offers only low wages and part-time hours.

Beaton shows the trap of gendered work even for those working-class people who have hard-won education — either you work a female-gendered job that doesn't pay enough to live on, or you go into a man's world, where you can pay your student loans but you get treated like shit. Beaton describes well the kind of whiplash this causes, ricocheting between these worlds, how trying to fit into one space and then the other, if even briefly, leaves you unable to fit into either.

Beaton is careful to include the context of Indigenous Peoples affected by the tar sands, and writes in the afterword that she regrets that "because this is my memoir, I can only tell you about my oil sands, where my world was very small and very white." Makes me think about another folk song, "Buffalo Skinners," a version of which was recorded by Woody Guthrie in the 1940s. It is about the labour issues — wage theft, injury, getting stranded — of workers skinning the bison. Unstated in the song is that the bison were killed by settlers to use hunger as a weapon against Indigenous Peoples of the plains. Those same people — Cree, Dene, Métis — have been penned on reserves like Fort MacKay, which is surrounded by toxic tar sands that are destroying nature and killing people, with cancer, and in other ways. And those Indigenous women bear the brunt of sexual exploitation by this migrant male work force. My people, Beaton's people, first came to Newfoundland and PEI and Cape Breton, economically displaced from Ireland and Scotland and France to do hard labour, but also to settle, and to displace and genocide the Mi'kmaq and Beothuk peoples. Now we migrate west to Ontario and Alberta, and do it all over again.

But then, people from social classes that never had to make choices like these condemn people like me or Beaton, condemn people who work in the tar sands, while they benefit from our labour, never having to get their own hands dirty. But all our hands are dirty. We are all the ducks, come from someplace else, stuck in the tar pit, trying to find some way out.

Megan Kinch grew up in a diasporic Cape Breton/PEI family in Toronto, and joined the army at 18 as a combat engineer. She is a construction electrician and writer, currently working on a memoir about her experiences in the military as a young woman.