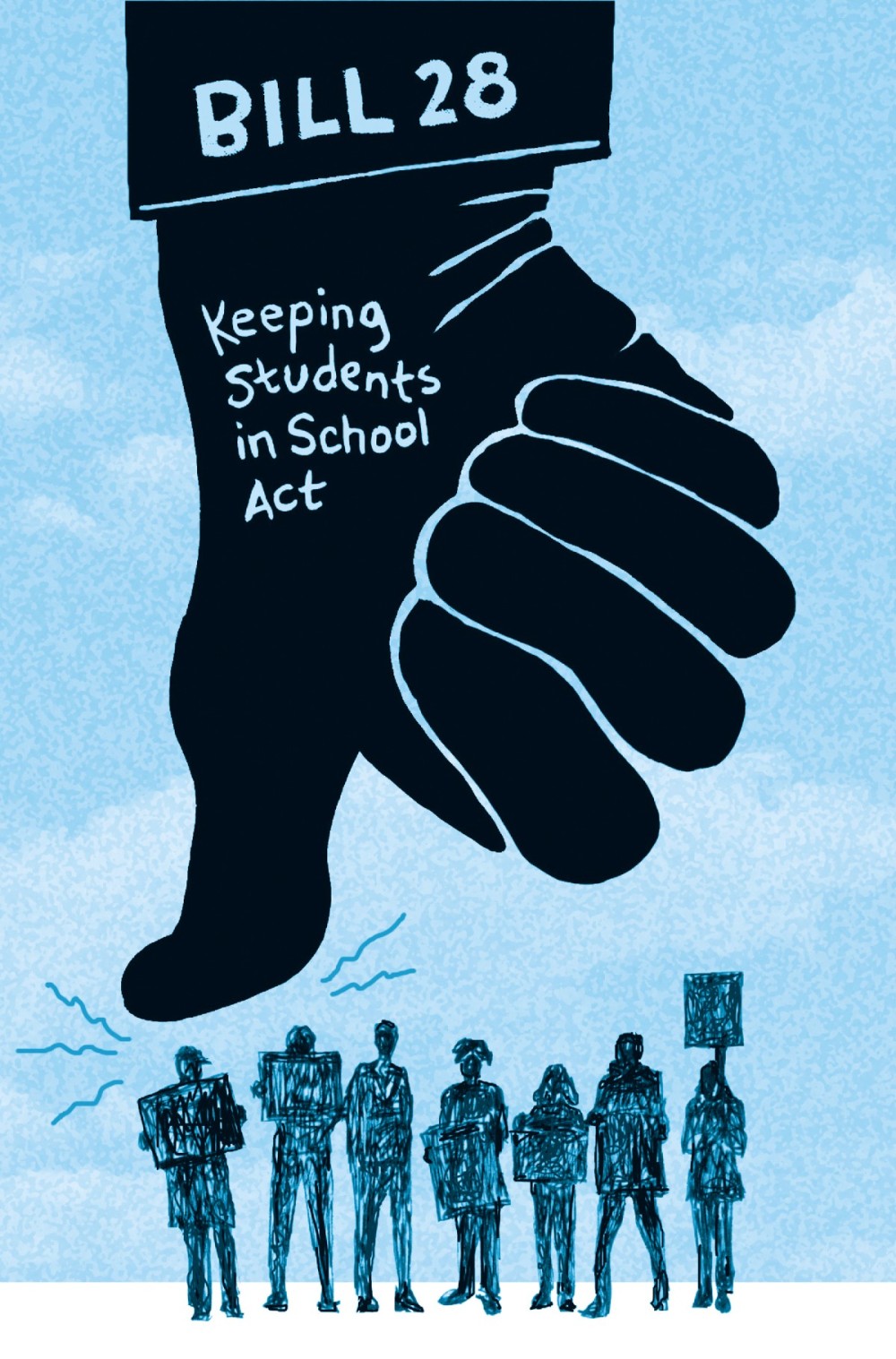

Bill 28, the keeping students in Class Act, 2022, had its first reading in the Ontario Legislature on October 31, 2022. The name was a distraction from the Act’s actual wording and intention, which were less about keeping students in class and more about removing education workers’ right to strike.

A quick look at the Ontario government’s language in reference to the Bill makes this clear: “The Act addresses the labour disputes involving school board employees represented by the Canadian Union of Public Employees. The Act provides for new collective agreements . . . The Act requires the termination of any strike or lock-out and prohibits strikes or lock-outs during the term of the collective agreement. The Act is declared to operate notwithstanding sections 2, 7 and 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Act will apply despite the Human Rights Code.”

The Doug Ford government couldn't overrule the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Human Rights Code, could it?

Charles Smith sees the attempt as one more Canadian provincial government’s attempt to erode the legally protected right to strike. The associate professor of political science at the University of Saskatchewan's St. Thomas More College is a researcher and author who has explored the historical interactions between labour unions and both federal and provincial public policy.

“It’s a long history, and we won’t get into all the details, but it’s kind of an awkward history,” Smith tells Our Times.

“There's a sense that workers have very few rights in their ability to withdraw their labour, well into the 20th century. But it’s actually more awkward than that, or more precarious: There seem to have been many strikes that occurred, but the right of contract was one that sort of prevailed in all cases, and employers had incredible abilities to starve out workers, to fire workers, to really blacklist workers. So when we talk about rights and corresponding duties, workers really had no ability to withdraw their labour and maintain their employment, outside of just raw class power, really forcing it through strikes.”

Toronto Typographical Union members were joined by some 10,000 supporters when they led the Printers’ Strike of 1872. The strike was part of the wider Nine Hour Movement, an international workers’ movement that took off in several Canadian cities in the 1870s and included workers from various trades, all seeking shorter workdays through the formation of Nine Hour Leagues.

George Brown, a Liberal and the publisher of the Toronto Globe, led the charge to have 24 strike leaders arrested for criminal conspiracy. When Brown faced public backlash, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, a Conservative, capitalized on it. Macdonald responded with the creation of the Trade Unions Act in 1872.

The country’s first labour law, the Trade Unions Act gave workers the legal right to join unions, but at the same time Macdonald passed another Act to ban picketing. That kind of incongruity has persisted through subsequent decades and governments.

Smith notes that the 1872 Act was a means to assuage conflict, rather than grant strong protections to striking workers. “The federal government kind of makes it clear that Canadian law allows workers to combine in a trade union, but then passes a whole series of laws in the Criminal Amendment Act to make it really difficult for workers to actually strike.”

Smith adds that the consequences of Macdonald’s double-edged Acts are still affecting Canadian workers today. “Well into the 20th century, there's no real right to strike, but workers who are organized, especially in the trades, have a lot of power because they have some sort of higher skill. They have the ability to withdraw their labour because it's not easy to bring in scabs.” Smith notes that where skill sets are easier to replace, it’s much harder for workers to strike.

Regardless of their specific skills, Canadian workers put the Trade Unions Act to the test around the turn of the century. “In 1907,” says Smith, “the federal government, because of the tons of strikes that are occurring throughout industrial life and trade sectors, brings in for the first time this industrial relations act.” The Industrial Disputes Investigation Act, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s brainchild, “doesn’t recognize collective bargaining or the right to strike, but it sort of allows the federal government to impose conciliation to bring both sides together and avoid strikes.

“That's probably the theme that's most important here,” says Smith. “That governments in Canada have been obsessed with making it hard to strike.”

The Industrial Disputes Investigation Act was a response to the lengthy coal miners’ strike that lasted from 1906 to 1907 in Lethbridge, Alberta. The Act was also informed by both the Canadian Conciliation Act of 1900 and the Railway Labour Disputes Act of 1903.

Strikes were (purposefully) disruptive; federal legislation supported conciliation as a means of reducing wide-ranging labour unrest. The militia had been called in during strikes by street railway (streetcar) operators in five Canadian cities between 1899 and 1914. Canadian Pacific Railway track maintenance workers went on strike from coast to coast in 1901, and another serious railway strike took place in British Columbia two years later.

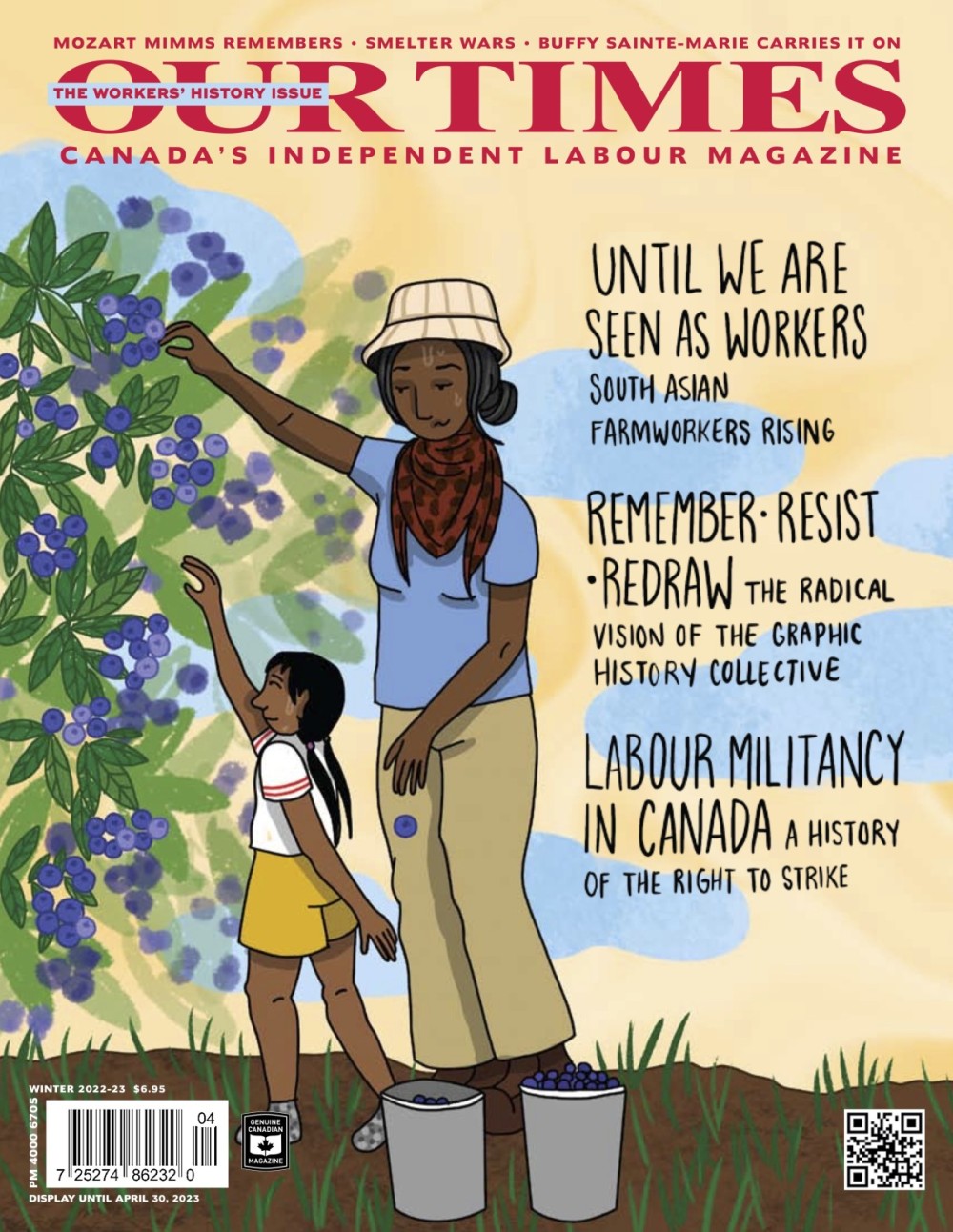

This article is from our Winter 2022-2023 Workers’ History Issue. Head to ourtimes.ca/magazine to see what’s in the latest issue.

The Industrial Disputes Investigation Act didn’t remove the right to strike; it just complicated and slowed down the process.

“It’s limiting, to make it hard to do,” Smith explains.

“You have to go through this onerous procedure of conciliation and getting a report and trying to get the government to solve the problems. All of these things delay and make it difficult, and of course the government refuses to recognize legal status for trade unions. They don't ever make it mandatory for employers to recognize unions, which also causes a lot of strikes. Recognition strikes are very common in this period.”

By the mid-20th century, a specific compromise brought greater recognition for organized labour, but at a price, Smith notes.

“It’s not until World War II that workers are able to finally get put on the agenda, finally able to get government to recognize the ability to organize and have it recognized by employers. But the trade-off is that they kind of limit their ability to strike. So in our system, which is more or less the same since the 1940s, workers have the ability to withdraw their labour at very specific moments, and that’s basically it.”

In response to a series of walkouts by United Autoworkers members at the Canadian Ford Motor Company in the early 1940s and an eventual 99-day wildcat strike in 1945 (after workers had endured a year and a half of failed negotiations), the Rand Formula was introduced in 1946. Seen as a compromise, the Rand Formula made the paying of union dues mandatory for any worker included in a collective agreement. At the same time, limits were put on workers’ ability to strike.

Smith explains: “They can strike after the expiration of a collective agreement, after they declare an impasse in bargaining, after they hold a strike vote, after they go through some sort of mandatory conciliation, after they go through some sort of cooling-off period. When you start doing that math, you’re like: It just takes a lot of time for us to wage a legal strike.

"And then everything else is illegal. So they can’t strike for political reasons; they can’t strike for recognition; they can’t strike to put pressure on an employer for disciplining a co-worker. You know, all these things are not legal. Legality becomes how we understand strikes in Canada after that,” says Smith. “So whether it’s legal or not starts to legitimize or delegitimize strikes in that way.”

Unions turned to the courts to protect members from unfair treatment during labour disputes. In 1962, the Supreme Court of Canada rejected the use of “permanent replacement workers” during strikes. “That comes out of a strike in Toronto [by hotel workers at the Royal York Hotel in 1961] where there was some nasty use of scabs, and the employers argued that striking workers didn’t have the ability to hold onto their jobs. And that would undermine completely the industrial-relations system, which at that point was only a decade-and-a-half old,” explains Smith. “I think legal forces had evolved at that point, at various levels, that it just became unsustainable for employers to make that argument.

“It was really judges using bold laws to try and reinforce their anti-labour bias at the time, and when the case made its way to the Supreme Court, the court recognized, I think, that if they were to go that way, the system itself would collapse. And that would probably have led to more strikes. So it’s all about keeping the peace, right?”

In the 1960s and 1970s, Canada saw “an upsurge in labour militancy” such as a two-week wildcat strike by the Canadian Union of Postal Workers in 1965, which started in Montreal and Vancouver before workers from 30 other cities joined in.

But an economic paradigm shift began in the 1970s. “Labour militancy again starts to be squeezed, and over time we start to see limitations involved, and that pushback by the state, to the point where we now see strikes are rare,” observes Smith. “We don't see many of them, and labour is in this sort of retrenchment mode.

“You start seeing a decline in private-sector union membership alongside periods of low inflation. There's this weird paradox: In periods of high inflation, we seem to have more labour militancy, which sort of we’re seeing today, but when you have periods of low inflation, we don’t tend to see as much labour militancy. Wages sort of dictate things in a specific way: When there’s periods of high inflation, we see labour pushing for shorter contracts; in periods of more predictable inflation, like one or two per cent, contracts are being pushed for longer. So you have those macroeconomic reasons and declining numbers [of union members] in the private sector. On top of that, public-sector members have never been as militant, in terms of their strike levels, so that formula means we’re seeing fewer and fewer strikes.”

The labour scholar says the tide has again begun to turn in recent decades.

“I think we’re starting to see an uptick here, because we’re seeing higher levels of inflation; we’re seeing governments being much more aggressive in attacking labour, and that’s what’s going on in Ontario . . . Then you have that moment between 2007 and 2015 when the Supreme Court reads into the Charter that labour has these constitutional rights.” Smith is referring to decisions such as Health Services and Support – Facilities Subsector Bargaining Assn. v. British Columbia, 2007. The government of British Columbia had passed legislation to quash certain provisions in healthcare workers’ collective agreements and which also made it illegal for unions to bargain for those provisions in the future. Unions challenged that legislation and the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that workers and unions in Canada have a constitutional right to engage in collective bargaining.

“I think that's made it more difficult for governments to do what they had previously done,” he says, “which is limit the ability of strikes, to [impose] back-to-work legislation, or to cap agreements or impose agreements and these sorts of things. So that partially explains how we got to that moment.”

Doug Ford’s Bill 28 was repealed on November 14, 2022, when the Ontario Legislature passed Bill 35, the Keeping Students in Class Repeal Act. “There’s a couple of different stories that I think are shaping this repeal,” says Smith. “I think the Ford government calculated that they could attack education workers, take away their right to strike, and then impose this agreement. So if we unpack that, there's two real struggles going on here.”

Smith explains: “One is a classic bargaining dispute between a government and a larger union, with that government basically saying ‘We’re not going to meet your wage demand; we’re going to impose an agreement and legislate you back to work.’

That's happened repeatedly throughout the last 40 years; that's very common.

“Then, on top of that, you’ve got this government saying, ‘and we're not going to let you take it to court and appeal our decision based on the charter, because the labour movement has won the charter right to bargain and strike, and we’re taking that away too.’

“And I think when they did that second part, labour rightfully freaked out, because they were like, ‘Oh my God — if a government can do this, then we’ll never have the ability to push wage demands at the bargaining table, because in the back pocket of every public-sector employer will be opposed agreements, capped wages, and no ability to challenge those decisions. Our entire existence is seriously threatened here.’

“And I think that decision is why you had such a mobilization amongst the labour movement. Once that got taken off the table — and that was a great victory, no question — then it just became about hard bargaining at the table. That’s when we started seeing pressure inside the labour movement [realizing that] ‘maybe it isn’t the best agreement, but we’ll take it and live to fight another day.’ And that's probably controversial, but, nevertheless, that’s more predictable in terms of traditional labour relations, as it were, as opposed to these heavy-handed legislative tools that Ford tried to use.”

In 2019, Ford also tried to cap public-sector wages at one per cent for each year of three years by bringing in Bill 124. But unions challenged that legislation and on November 29, 2022, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice ruled that the Bill was “void and of no effect” because it violates workers’ freedom of association under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, specifically in relation to collective bargaining and the right to strike.

Smith says despite the court's decision on Bill 124 and the repeal of Bill 28, Ford likely won’t abandon his familiar tactics.

“I think we’ll continue to see governments try to use back-to-work legislation. It's almost like a Canadian thing these days: Public-sector workers threaten to strike; it's in a politically sensitive area or just politically inconvenient for the government, so they use this tool, which all governments have used. You know, the Liberals have used it federally; the Conservatives have used it federally; New Democrats have used it provincially in Saskatchewan; the Liberals have used it in Ontario: every government will use back-to-work legislation to end politically inconvenient strikes, usually against public-sector workers. But Harper used it against the airlines, so he would use it against private-sector unions too.

“That's a fairly common thing, and I don’t think Canadian labour has developed a really good strategy to push back against back-to-work legislation.”

Following the Canadian Supreme Court’s 2015 decision on Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v. Saskatchewan, there was hope that the introduction of bills to curtail workers’ right to strike might lose popularity with governments. The Supreme Court ruled that the Public Service Essential Services Act, 2008 and Trade Union Amendment Act, 2008 prevented workers from withdrawing their labour and unfairly defined “essential services” in terms that favoured the employer.

Smith observes that governments have subsequently gambled on anti-strike legislation. “They don't care — they’ll legislate workers back to work and face the legal consequences years later and, by that point, the crisis is over. The political crisis has been solved, and government has calculated that it’s worth the political and legal risk.

“We haven't really seen a decline in the usage of back-to-work legislation since 2015, even though that legislation takes away, legally, the right of workers to strike. So the problem, I think, is that labour is still vulnerable to these tools, even with their constitutional ability to strike or bargain restored with Bill 28 being repealed.

“I think, had that not happened, every Conservative government in the country would have been very comfortable using the same tool. So that was a great victory, but the back-to-work bills are still going to come, whenever workers strike and it’s politically inconvenient for the government that they’re doing so.

“Now we have to think about what strategies beyond the courts, in my opinion, need to be thought through. That’s the big question that needs to be put on the table, I think, right now.”

Smith believes there is no answer to that question, at least not yet, but there are “lots of ideas on the table.” He says, “I think unions that are not directly involved in these disputes need to be more active on picket lines, because if you defy back-to-work legislation as a worker in a unionized sector, the legislation is tied directly to that union in particular. So the broader labour movement can play a role here, where you can have permanent flying squads [i.e. unofficial groups of autonomous workers, acting independently of their union leadership]. You can have more solidaristic strike funds that can be used to circumvent strike legislation, because without some kind of coordinated, broader effort, every union that tries to strike in this situation — especially public-sector workers who are politically inconvenient for government — the government will use back-to-work legislation.”

Smith estimates that Canadian governments have used back-to-work legislation between 146 and 148 times since the 1970s. “We're talking about a very consistent pattern: Workers threaten to strike; government sees it as inconvenient, legislates them back — within a day or two, or a week or two, usually not much longer than that. Sometimes those actions get struck down in the courts years later, but often they don't, and labour has lost that fight.”

Strikes draw attention to important matters that may not otherwise be resolved. “There's some really good examples of where governments have legislated workers back to work and the underlying problem that led to the strike in the first place never gets solved,” he notes.

With CUPW, the Trudeau Liberals legislated postal workers back to work in 2017 using the excuse that the government was worried about Christmas being interrupted. “But,” says Smith, “I think that strike was about worker health and safety and all kinds of serious issues that carriers had to deal with — rural mail routes were dangerous.”

The problems CUPW wanted addressed in 2017 were left unresolved after nine months of negotiations, despite the appointment of a conciliator. On the table were the protection of quality employment and full-time Canada Post positions, health-and-safety issues and gender equality (rural and suburban letter carriers, mostly women, were earning 25 per cent less than their urban counterparts, who were mostly male). CUPW members conducted rotating strikes across the country until November 27, when the federal government brought in Bill C-89, the Postal Services Resumption and Continuation Act, which imposed heavy fines on striking workers.

Smith relates that he saw an interview with one of the key bargaining people years later who said, “We’ve never dealt with that issue. We went to arbitration, and we didn’t really get what we wanted, and we were legislated back, and this is still a major problem.”

Smith believes that indeed “we never really get the answers to those problems from an imposition. It just ends the political crisis — for the government. So labour has to start getting creative here.”

But he also urges us to remember that the repeal last year of Bill 28 in Ontario represents a significant milestone. “I don’t think that we should take away from the fact that labour mobilization won the day and forced the Ford government to back down. That's a victory, no matter how you want to look at it.

“I think the next question is how to respond the next time the Ford government, or a government like Doug Ford’s, will just skip the Charter stuff and take the gamble on back-to-work legislation, which is what they’ve been doing for 40 years.”

The labour movement, he says, just needs to “think down the road a bit.”

Melissa Keith is a former radio broadcaster and an award-winning freelance journalist. She lives in Lower Sackville, Nova Scotia.