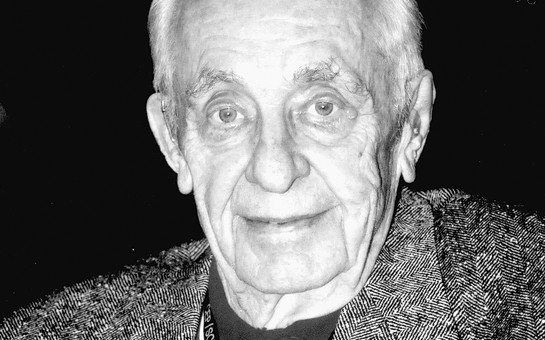

Neil Reimer passed away at the age of 89 on March 29, 2011. We are re-posting this Our Times 2004 interview with him in his honour. He was, says Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union president Dave Coles, "a giant of the labour movement," and will be missed.

********************************************************

In 1942, I went from being a student at the University of Saskatchewan to working at the Consumers Cooperative Refinery, in Regina. I was assigned to the refinery, which was considered to be an essential industry, by the War Labour Board. Most of us who worked there were farm boys. We weren't used to industrial life. Here, all of a sudden, your hours were managed; you were told when to work; what to do; how; and to be careful what you said. It all seemed very strange to me.

"At first the workers thought I was being hired by the company to fight the union, so they decided to send four people over to talk to me, to see if it was true. I said, 'You know, we're not going to get very far at 35 cents an hour! I'm surprised you haven't got one already.'"

(Photograph: Robert Hatfield)

When I got to the refinery, there was talk about forming a union. I was only about 19 at that time. At first the workers thought I was being hired by the company to fight the union, so they decided to send four people over to talk to me, to see if it was true. I said, "You know, we're not going to get very far at 35 cents an hour! I'm surprised you haven't got one already." I joined right away. And now I was a young man on the committee. The talk always was that it was risky to be in union activity, for fear of getting fired. I didn't have a family; I didn't have kids; I wasn't married. So it wouldn't be so bad for me to get fired.

HAVING A UNION WOULD BE A POSITIVE THING

Some were saying, "You don't need to have a union for a cooperative." Others said, "You don't need a union if you're CCF." Still others said, "You don't need a union, with all the technologies." But I could never see that. I still felt that having a union would be a positive thing. After all, if there was going to be a boss, we were not going to be the same as the boss: we wouldn't have an equal say. So, we set out to organize the refinery.

In those days, we had to ask for recognition from the companies. The federal government had jurisdiction over labour legislation and there was no legal way of getting union recognition, except in getting the employer to recognize you. So, after we had enough people signed up on cards, I was asked to help present the cards and ask for recognition. So, I went into the office with another fellow.

The white-haired plant manager was from Texas and was way over six feet; he towered over you. He was a good actor, but I didn't know that at the time. We said, "Mr. Males," we have enough people who want to have a union, so we're going to ask you for recognition." He got all red in the face and said the day he recognized the CIO would be the day he'd shut down the plant. I don't know where this came from, but, I said, "Well, Mr. Males, we'll spare you the

bother and shut it down ourselves."

That led to some discussion, and we got the union recognized. The Canadian Congress of Labour (the Canadian Labour Congress's precursor) chartered us as the first local of oil workers in Canada.

LEARNING TO SPEAK THE LANGUAGE

A lot of us were very impressed by the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations), which was much more progressive than the Trades and Labour Congress, in Canada, and the American Federation of Labour. They wanted to organize workers by industry, while the craft unions wanted to keep organizing industries along a craft basis. But a lot of people wanted everyone to be in one union. During the Depression, that sounded pretty darn good.

After a while, I was asked to become a representative for the Oil Workers International Union (Later known as the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union), and I was assigned to Alberta. Now, I knew the industry. I knew the oil workers' culture. I was one of them. And it is very important, particularly in oil, that you know what you're talking about. You have to learn to speak the language!

In the oil industry - the petrochemical industry - there's a lot of technology; a lot of skilled people. You had to have Grade 12 to get in, and you had to know something about chemical reaction. As an organizer, if you don't know what you're talking about, it's not very likely that you're going to organize anyone. I think that just only follows. If you're going to represent somebody, you've got to know the business they're in. It's important to know the skills people have and the kind of jobs they do.

I knew the industry mostly from the refinery and sales, but I didn't know beans about drilling. I got a smattering of information about drilling by talking to people in beer parlours and restaurants. They were always happy to talk about their jobs. But I decided the best way to find out would be to watch them at work. Texaco was drilling an oil well about 15 miles out of Edmonton, so I drove out there every day and parked on a hill and watched the workers "spudding in." Of course, they wanted to know what I was doing. I just said I was interested in writing an article, or something like that. But I watched them drill their oil wells; I saw them hitting oil and it spurting out. And so I could engage in a conversation about the drilling process.

What the union hadn't told me was that there had been six staff representatives here in Edmonton prior to me, and they'd all thrown up their hands and said, "It's not possible to organize in Alberta." I wasn't aware of that. But I knew that it was a long haul. During the war, there was such a pent-up desire for improving working conditions that people were ready: say there was a meeting at the plant gate and you made a speech, you'd sign up a whole bunch of people. The oil here was discovered in 1947, after the war, and I was assigned here in 1950, so that era was gone. You had to have an entirely different organizing approach than what the labour movement had used before.

INSTEAD OF MAKING SPEECHES, I GOT QUIET

So, instead of making speeches, I got quiet. I opened up an office in Edmonton, which was much smaller then. At that time, on Saturdays in particular, a man and his wife would come downtown, and, while the missus was shopping, the guys would be looking around for something to do. So, they would come and visit me, and we talked union. This was an educational process, and the number of people that dropped in increased all the time. We developed a good core of people this way that would go out in the plant and know what they're talking about in terms of forming unions.

Having people inside the plants to help me organize was a big help. You can't do it very well just from the outside. One day they said to me, "Aren't you going to ask us to join a union?" I said, "Well, it's your choice. You should know what you want. If you want to sign up, well, here's the card!"

ORGANIZING IS A SKILL

Organizing is a skill. Everybody who is a good organizer does it their way, whatever they're comfortable with. Very often, however, a union's administration wants the organizer to fit into their administrative structure. Well, that really kills the effectiveness of an organizer. You have to give them their head. (That's horse talk for, "Don't rein them in.") I know when I came to Edmonton, I had only been here a week and they were already bothering me from Denver, Colorado about how many people I'd signed up. I hadn't even seen anybody yet. I always told our union, if you get a good organizer, protect that person, because they're few and far between.

EVERYBODY NEEDS SOME RECOGNITION

Very often the organizer never gets the recognition they deserve. A good organizer will make the people who organized feel that they did it all, because it's not the organizer's organization; it is the people's organization. So you go away knowing very well what you've done, but you give all the credit to the people who decided to join the union and run it afterwards. People can burn out that way. It helps to have a long-term view. Plus, everybody needs some recognition and appreciation. I think it's up to the organization to understand that kind of process that organizers go through.

The best thing about organizing is winning, and the worst is losing. But losing can be winning. The first time I lost at a refinery, the guys all quit and went to another company where we won. So, we never really lost. The other thing, of course, is that you have to accept the fact that, in organizing, workers will sometimes let you down. So many times we've signed more people than we got votes at a certification vote. But then that's understandable, particularly here in Alberta, with our conservative, anti-union governments. On the other hand, I'm a firm believer that if you give them the information they need, workers will do the right thing. And this time we won. The oil workers are a good group of guys. They're militant, and they will fight for what they think is right just as well as anybody else. - OT

***********************************************************

SIDEBAR: LIFE LESSONS FROM A SMALL PRAIRIE FARM

My parents came to Canada from the Ukraine in 1927 when I was six. My Dad was an expert farmer and we settled on a farm between Kindersley and Eston in Saskatchewan, about 75 miles from the Alberta border. We did mixed farming. We had wheat, cows, and we had horses. We had the misfortune of coming here just before the Depression started. It was tough. There was drought, soil drifting, and the cupboards were bare.

My brothers and sisters and I had to help our parents. On the farm, you learn a work ethic that is difficult to replace. Everybody pitches in and, unless you do something, nothing happens. You want milk? Well, if you don't milk the cows, you won't get milk. If you don't put the seed in the ground, you're not going to get a crop. It's a real lesson in life, and something that sticks with you.

I've always marvelled at the women of the day, how they would manage things. They knew how to deal with adversity. They were very ingenious. We had very little money, and our treat on Sunday was Cornflakes. Of course, we could slaughter a pig once a year and have that, but that really wasn't enough. I don't know how they did it, but the women would feed their families. I always said, "They made nothing do."

It was very difficult for the women, since they didn't associate with people other than their own family, the nearest neighbour likely being more than a mile away. It was easier on the men, because they weren't so isolated. The men would go into town and do their commerce and be exposed to the village people and to other farmers. The women generally stayed home to look after the family and do the cooking. It left them isolated.

And then, of course, my mother couldn't speak any English. She could speak six languages, but English and French weren't one of them. We had bought a radio and my mother decided to use it to learn the English language. She had a good ear. She had been a leading soprano in a huge choir in Russia. She would listen to the radio, write down some words and then ask us, when we came home from school, what they meant. After we got a phone, she might phone and ask the neighbours. By the time she and my father retired in Saskatoon, she spoke good English.

The elementary school was in Madison, six miles away from our farm. We would hitch a horse and go there in the morning, and take the horse back at night. My older brother was nine years older than me, and would take us. Then he quit school, and my sister and I had to take care of it. I guess I was nine years old. My Dad gave us a very good horse. If there was a blizzard, all we had to say to Nellie was, "Nellie, go on home," and she would find her way home.

In 1937, we had to sell all our horses and we bought a tractor. We had no alternative because the horses were dying then, of starvation. Usually the horses were put out on the range for the wintertime, with straw stacks, but there were none because of crop failures. It was a universal problem. In some respects, us young guys were happy getting a tractor. But we also loved the horses. One time we were on the range, and a horse came over to the gatepost and whinnied and died.

These were sad stories. I remember my Dad selling cattle. The cattle had to be shipped to Winnipeg, where the market was. But they didn't bring in enough money to pay for the freight.

Even after selling the cattle, we still owed the CPR money. So, my Dad couldn't afford to keep them, and he couldn't afford to sell them. So he had to shoot them. I remember tears running down his cheeks. He had to slaughter the young herd, because he couldn't keep on feeding them. There was pasture, but that pasture was pretty well grazed out. I guess it was one of the saddest days in his life. He was a sort of animal lover. These were indelible impressions.

I went to the University of Saskatchewan, to, what we called at that time, "the best agricultural college in the British Empire." I remember the first year in Saskatoon. I'd never been to the city. I didn't know what a city looked like. It was a tremendous change. I had to sell my books to get home for the summer.

I was, of course, interested in what the farmers were doing. In Regina, they were building the world's first co-op refinery. In Saskatchewan, we already had some experience with cooperatives in the oil industry. People had already developed a consumers co-op for distributing fuel oil, but Imperial Oil would bring down the price in the area where a co-op had opened, and drive the co-op out of business. So it was decided that the best thing to do was to have a province-wide co-op.

That way, if Imperial Oil wanted to run the co-ops out of business, they'd have to lower the price throughout the province, and that never happened. As kids, some of us had that background that our parents had experienced. - N.R.

SIDEBAR: UNIVERSITY IN OVERALLS

The refinery operation was such that, if things were running well, there wasn't very much to do, so there was always a meeting of some kind going on. There were all kinds of political arguments. There were technocrats; there were Liberals; there were CCFers; there were Communists (Labour Progressives) and what-not. Everybody was arguing and debating. I always called the refinery a "university in overalls." It was an education, the debates we had. It was a

great experience, really, that you couldn't get anywhere else.

During the 30s, there were tremendous debates going on around the whole province about what direction we should be going in, because people knew - the farmers knew - that private enterprise had let us down. Saskatchewan was a very politically aware province. Everybody knew where everybody stood. But they all helped each other; they never allowed their politics to stand in the way. They had big arguments on a Saturday night about what was right and what was wrong. But, if somebody was in trouble, they were all ready to help the next morning. The advantage of the 30s was that everybody was poor. There was no distinction, really. -N.R.

This article is an early instalment in Our Times' series "Talking About Organizing." If you would like to add to this conversation about organizing, contact the editor or find us on Facebook. Neil Reimer became the Canadian director of OCAWIU in 1951. Under his leadership, it grew from less than 1,000 members to more than 20,000 in 10 years, and eventually the Canadian members received autonomy. The OCAW eventually became the Energy and Chemical Workers Union, one of the three founding unions of the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada. Reimer was elected as a vice-president of the Canadian Congress of Labour, and stayed on the executive until 1974, by which time the CCL had become the Canadian Labour Congress. He was the first leader of the Alberta NDP, holding that position from 1963 to 1968. He retired as national director of the ECWU in 1984. In October 2004, Our Times was honoured to receive the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers' Neil Reimer Award, given bi-annually to individuals or organizations in recognition of their outstanding contribution to the public good.