Kids Can Press

Toronto, 2007

136 pages, $16.95

ISBN-13: 978-1-55337-649-1

Review by Janet Nicol

"So there Emily had stood ever since, shoulder to shoulder with the girls on either side, part of a group of eight around the table, snipping, snipping, snipping, absolutely mute. But would it hurt to smile?" So began the first day of solemn work, almost a century ago, for 12-year-old Emily Watson, who was learning lessons in a Toronto garment factory instead of a Grade 4 classroom.

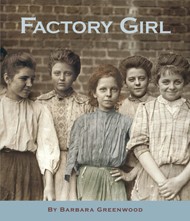

But Factory Girl, aimed at readers aged 10 and older, is more than an engaging historic tale. Alternating chapters explain the true facts behind the lives of working children. And like in any story told simply and directly, author Barbara Greenwood's blend of fiction, fact and actual photographs of young labourers powerfully illuminates society's capacity to exploit the most vulnerable among us.

The Watson family's troubles begin as the story opens in 1912. The father, who is working elsewhere in Ontario, has stopped sending paycheques to his wife for an unknown reason (disclosed in the closing chapter). The two eldest of the four Watson children are forced to find work. Ernie becomes a street scavenger and Emily reluctantly leaves school too, though her teacher, Miss Henderson, will support Emily throughout the ordeals to come.

When Emily is hired at the Acne Garment Factory, she meets men and women on the assembly line making "shirtwaists" (women's blouses) and other clothing for retail stores such as Eaton's. Emily is a clipper, working alongside girls her age, whose small, nimble fingers are considered useful by garment employers for performing delicate snipping tasks.

Emily discovers that, unlike herself, many factory girls do not have origins in the British Isles. As the author explains, beginning in 1880, impoverished immigrants flooded Toronto from eastern and southern Europe, making the expensive and uncomfortable three-week journey across the Atlantic only to find themselves "stranded in a confusing world where few understood their language and some took advantage of them." Hundreds of these immigrants toiled in Toronto's factories.

Emily makes friends with Magda Takac, helping her with her halting English, both in speaking and reading. In return Magda shows Emily the ropes at work. Employer injustices are chronicled as Emily receives paycheque deductions for making mistakes and deals with the lack of cleanliness and safety on the factory floor.

It takes an interloper, E.D. Harris of the Globe newspaper, to awaken Emily to the need for action against her working conditions. But not before a factory fire leads to tragic deaths. Emily emerges scarred but wiser and stronger.

The book's non-fiction chapters are informative and wide-ranging in scope. Descriptions of old Toronto, for example, include contrasting Emily's neighbourhood with wealthier parts of the city. An actual factory fire that made a difference in the lives of all garment workers is also recounted: that of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City in 1911.

Factory Girl concludes with information about children joining the greater trade union struggles and features the legacy of Clara Lemlich, an American garment worker organizer. The author also observes that while the battle against child labour and sweatshop conditions may be won in North America for most children, in other countries, sweatshop conditions still exist.

One of the book's strengths is the many photographs, both Canadian and American. Some of the most striking were taken by Lewis Hine, an American school teacher who began using the camera in 1904 to record the plight of child workers. He captured weary girls and boys. Many look old beyond their years with facial expressions both spirited and pensive. Additionally, a collage of tiny black and white photos of children of the era effectively frame the book's pages.

Readers also learn about the various roles inside the garment factory, where jobs were segregated by age and gender. The clipping girls, Emily among them, were unskilled and underage. Employers found ways to keep them out of sight when inspectors visited. The girls clipped loose threads from finished garments. Teen girls and young women worked as seamstresses. Each operating a sewing machine, they were pushed to work at top speed on one part of a garment. Drappers could be male or female and earned higher wages doing the skilled work of turning a design into a pattern. Cutters and pressers -- workers who cut the patterns and pressed the garments -- were always men.

For women in general at the time, housework, and homework as a seamstress, were considered less desirable jobs. Considered more prestigious were jobs as nurses, teachers, milliners (hat makers), sales clerks, office workers and telephone operators.

Children also worked at textile mills, glass factories, canneries, biscuit and other consumer product factories, and in coal mines.

The fight to improve conditions for children was led by trade unions but also supported by benevolent societies, churches and settlement houses. The author profiles various North American reformers, including Canadian J.S. Woodsworth, who preached about the "sin of indifference."

While the inclusion in this story of influential American reformers in New York and Chicago indicates these issues crossed borders, it may have been equally intriguing if the author had explored similar situations in Montreal, Halifax and Vancouver. And who were the labour leaders in Toronto leading the protest against child labour? These investigations would not only have enriched the readers' knowledge, but also added to Canada's labour history. A short bibliography (including websites) would also have been a helpful addition to the text. Factory Girl does include an index at the back of the book, as well as a short glossary and a brief chronology of the fight for child welfare reform.

Greenwood has written other Canadian history stories for young readers but with this book she offers a unique format and an under-represented topic. She also succeeds in tying together the social issues and protests of the past with the urgent need for awareness and action in the

present.

Her stories, both crafted and factual, will give young readers important ideas and hopefully lead to a compassionate response to the continued harm endured by children in factories and other workplaces around the world.