Last year marked the centennial anniversary of the Winnipeg General Strike, a milestone in the history of the Canadian labour movement. With deep gratitude, we salute these labour pioneers who did the heavy lifting and ground clearing for future generations of trade unionists. We continue to walk the path inspired by their legacy.

In exploring the wealth of recorded working-class history in Canada, I can never help asking whose stories are missing. Who are the people we consider 'workers' historically? Or more precisely, who were the ones excluded by organized labour then?

This is when my own digging started. I stumbled on the fact that in April 1919, close to 2,000 Asian shingle workers organized a historic strike in British Columbia’s Lower Mainland to resist a discriminatory 10-per-cent wage reduction. The strike lasted for 40 days.

But what was the historical context? How did these workers have such courage, tenacity, and probably, what seemed to many, the audacity to strike? How did these workers organize and build such a cohesive force?

With these questions, I began my excavation project, to bring to light some long-buried labour struggles that few historians have written about. It is an act of reclaiming the space, centred on the narratives of many early labour pioneers who were deemed others, whose voices and activism were dismissed; and whose struggles have yet to be embraced and celebrated by the labour movement as a whole.

Join the Treasure Hunt

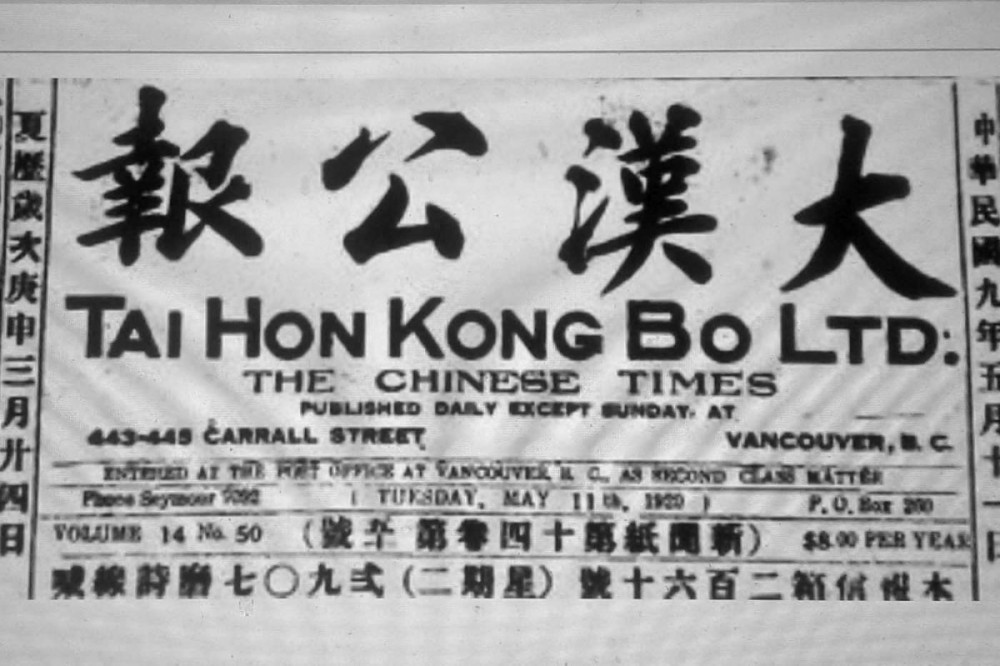

The potential scope and depth of the project are immense, the work akin to a treasure hunt. I have focused my search primarily on the early labour struggles within the Chinese Canadian community. Exploring Chinese-language source materials is especially exciting — both scholarly work and community publications including the longest-running Chinese Canadian daily newspaper, the Chinese Times (Tai Hon Kong Bo), which served the Vancouver community from 1914 to 1992.

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE CHINESE TIMES’ FRONT PAGE ON MAY 11, 1920: SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY DIGITAL LIBRARY COLLECTION

This excavation project is, above all, an exercise to dispel stereotypes of Chinese people as docile strikebreakers. In the stories below, it is clear that the early struggles of Chinese Canadian workers were about dignity and fairness. Their militancy and resistance were motivated by rage over overt and systemic racism, over the denial of their rights, and over their exploitation as workers on the basis of race and class.

With this article, I want to invite other labour activists in Indigenous, Asian, Black and other racialized communities in Canada to join the excavation project and add richness to the fabric of Canadian labour history. It’s time to share these untold tales of resistance for generations of labour activists to come.

_____________________________

PHOTOGRAPH OF CHINESE CANADIAN WORKER IN A SHINGLE MILL: FROM SALTWATER CITY: AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY OF THE CHINESE IN VANCOUVER, BY PAUL YEE (ROYAL BRITISH COLUMBIA MUSEUM)

Chinese Canadian Shingle Mill Workers Rise

In the early 1900s, Canada’s lumber industry employed large numbers of Chinese workers, paying them substantially lower wages than those paid to white workers. Chinese Canadian workers represented 70 per cent of the workforce in the lumber mills in BC, and the militancy of Chinese Canadian shingle mill workers grew over the years.

In Paul Yee’s 2006 book, Saltwater City: An Illustrated History of the Chinese in Vancouver, he describes the working and living conditions in the shingle mills as dismal. Workers were paid according to a piecework system. Yee includes an excerpt of a 1980 interview conducted for B.C. Archives by Theresa Low with Jung Hong-len, who began working in a mill in 1915. Jung recalls:

“The mill had so many mosquitoes, you had to wrap up your face to work there. The sky would get dark, with so many mosquitoes! . . . The stronger men were faster and they earned more money — 11 cents for a thousand shingle pieces. You did 10,000 and earned a dollar or so. The cutter had to work fast, so he’d find someone who could pack fast enough for him. If you cut fast, you want a fast packer. If you cut slow, you get a slow packer . . . Once you worked in the shingle mill, you always worked there, because no other work gave you as much money. Did I like it? You just had to be careful! The whites didn’t like the work, because they were afraid to lose their fingers.”

Bargaining for Equal Treatment

In 1916, Chinese shingle mill workers organized the Chinese Labour Association (CLA) and used strikes as a means to bargain for equal treatment and wage parity with white workers. The first major strike was in the sawmills of Vancouver and New Westminster, with Chinese workers pushing to shorten their working day from 10 to eight hours, in order to bring their hours in line with those of white workers.

The white woodworkers represented by the International Shingle Weavers Union of America began to recognize that they could not make any gains if they kept excluding their Chinese co-workers, who formed a majority in the mills. The union representing white workers approached and persuaded members of the CLA to strike for shorter working hours. A joint meeting was called on Sunday, July 17,1917, with the Chinese Times reporting it the next day as an announcement in the City News section. (Translations below of excerpts from the Chinese Times are my own.):

There was a Union meeting yesterday to discuss our demands to employers to reduce our working hours to eight hours a day. If the demand is not met, we will strike. We will hold another meeting next Sunday to make the final decision on our strike action. All Chinese mill workers please distribute the Chinese-language leaflets to your co-workers and encourage them to attend the next meeting. In order to achieve our goal, we need to know where everyone stands.

Whether you are small business operators or workers, we have all experienced harassment and discrimination from white workers. This is the first time (the white workers’ union) has contacted us to join their action. Given the fact that seven or eight of every 10 sawmill workers are Chinese, the union realizes that their actions will fail if they do not include us. So, although we know their invitation is sincere, we are also aware that the union is just being strategic and has its own motives for reaching out to Chinese workers. (July 18, 1917)

Well-Founded Mistrust and Skepticism

So, while members of the Chinese Canadian community recognized the significance of the ‘first-contact’ gesture displayed by the Shingle Weavers Union, they felt it important to proceed with caution. Their tone of mistrust and skepticism was a direct result of the racism long inflicted on them by white-workers’ unions.

The strike began on July 23, and the Chinese Times reported:

July 24, 1917: An industry-wide strike began on July 23 as employers refused to lower working hours. A total of 2,500 white, Chinese and East Asian workers will be out on strike. This is the first time there is a united front of all mill workers. Of the 15 mills, only six are still open.

July 24, 1917 afternoon update: We have heard that the employers plan to hire white women to replace the Chinese strikers. Hiring took place last Saturday and the white women workers went in for training. But many decided not to take the backbreaking job. When asked about the impact of the strike, employers responded that they are well stocked so they are not worried.

July 25, 1917: Six more mills have re-opened as the strike continues. The employers have not hired any white women workers. Some Chinese workers who are not participating in the strike have been threatened and harassed by white workers.

On July 28, there was a final brief mention in the Chinese Times, noting that 75 per cent of the mills had resumed operation.

A Sense of What to Expect

Even though this first strike was unsuccessful, the whole experience served to ‘inoculate’ (in our contemporary union organizing language) these strikers by giving them a sense of what to expect during a strike. It also led them, and others, to recognize the power they held as workers. In fact, the sawmill workers coming together as a united front laid the foundation for a successful strike action just one year later.

On April 13, 1918, the Chinese Times reported on that strike:

Western Canadian Mills’ Asian workers went on strike to demand a reduction of their daily working hours. After bargaining, the employer had agreed that the workers could work for nine hours and receive 10 hours’ pay. When the workers got their next pay, though, they received nine hours’ pay. This means the employer reneged on the agreement. The Chinese, Japanese and Hindu workers stood firm. The employer refused. So the workers went on strike on Tuesday. After two days, the employer relented and accepted the strikers’ demand. The workers returned to work on Thursday.

Shared Understanding, Deeper Solidarity

The victory and the shared understanding built among Chinese, Japanese and South Asian workers deepened solidarity and paved the way for another action: the general strike led by Chinese shingle mill workers in 1919.

As mentioned, the key issue sparking the long strike of 1919 was pay reductions.

On March 7, 1919, the Chinese Times reported the strike:

The sawmill employers’ scheme was to lower the wages of Chinese workers. From this month onward, machine operators will lose two cents per thousand pieces, packers one cent per thousand pieces, and general labourers, ten cents per dollar earned. All Chinese shingle workers find this unacceptable and have decided to stage a general strike.There are about 800 Chinese workers in more than 15 mills. This show of force and unified support for strike action is unprecedented in the Chinese community.The strikers have vowed that they will not return to work if the wage reduction is not withdrawn.

Chinese Times Editor’s Note: Among the Western [white] workers, there is a union for each occupation to serve as a protection. Only Chinese workers have no such organizational support. If this situation does not change, it will weaken our solidarity. Chinese workers are now being targeted by employers, but we do not have an organization to build a united force to counter and fight back. It is time for our Chinese shingle workers to reflect and decide what to do.

The Birth of a Union

The call to form a union resonated with Chinese shingle workers, and the Chinese Shingle Workers Union of Canada was formed. The union set up offices in Chinatown and organized the strike. The employers responded by starting a school to train war veterans to replace the Chinese workers, but the plan failed.

After 40 days of striking, the workers succeeded in recovering their original wages. With their new-found confidence, they demanded higher wages in April to compensate for the strike losses. Once again, they won. The union also advocated for, and won, higher wages for part-time workers.

In 1920, the Chinese Canadian shingle workers' union appointed representatives to every mill. From plant to plant, workers went on strike against poor treatment and harassment.

_____________________________

This is an excerpt from “Excavating Narratives of Resistance: Early Chinese Worker Militancy in British Columbia,” an article by Winnie Ng which will appear in the Fall 2020 edition of Our Times magazine.

Winnie Ng is a long-time labour-rights activist, educator, and community organizer with a deep commitment to anti-racism, equity and worker empowerment. She served as the Unifor-Sam Gindin Chair in Social Justice and Democracy at Ryerson University from 2011-2016. She is currently an adjunct professor with Ryerson’s School of Social Work.