During and after the January 19 National Day of Action in solidarity with Tim Hortons workers there was virtually no comment out there about the extent to which social media made it all possible. You know, the sort of thing you would have read here even five years ago. Online organizing, of even the smallest events, is now the norm.

All those digital efforts are very well; all the Facebook events and posts and all those tweets. But the success of those Tim Hortons actions, locally, provincially and nationally, rested on the painstaking work done by the $15 and Fairness campaign(s) over years; on the 25 years of organizing done by the Northumberland Coalition Against Poverty (NCAP) in Cobourg, Ontario, where as you will recall, the first and, I believe, the largest Tims rally took place; on the trust union members put in the Toronto & York Region Labour Council when it called on them to come out; on Leadnow, which told a grandma in Saskatoon that if she picked a Tim Hortons and could get five people to a rally there, they would add 10.

Nice to have a spark and some lighter fluid but a big pile of wood is what burns. The $15 and Fairness campaign and the rest of them cut down the trees, dried the wood, piled it nicely and in the right place and made sure it all caught when it needed to.

The Cobourg (population 18,500) rally on January 10, part of a series of Ontario-wide rallies that preceded the national day of action, drew about 300 attendees, which included some Durham Region Labour Council folks who came to town.

For the most part it was the work done by the Northumberland Labour Council, various local unions in the area and the Northumberland Coalition Against Poverty that carried the day. LabourStart Canada helped out a bit, I hope, and there was a lot of online traffic using established but not labour-related networks. So, many of the good folks from local social-justice, international-development and other organizations, clubs and associations came by as well. Pardon a bit of small town pride: had Toronto seen the same percentage of its population out in one day, there would have been close to 50,000 people clogging the drive-throughs.

Given the taken-for-granted extent to which the organizing of all this happened online it’s worth taking a peek at how it developed.

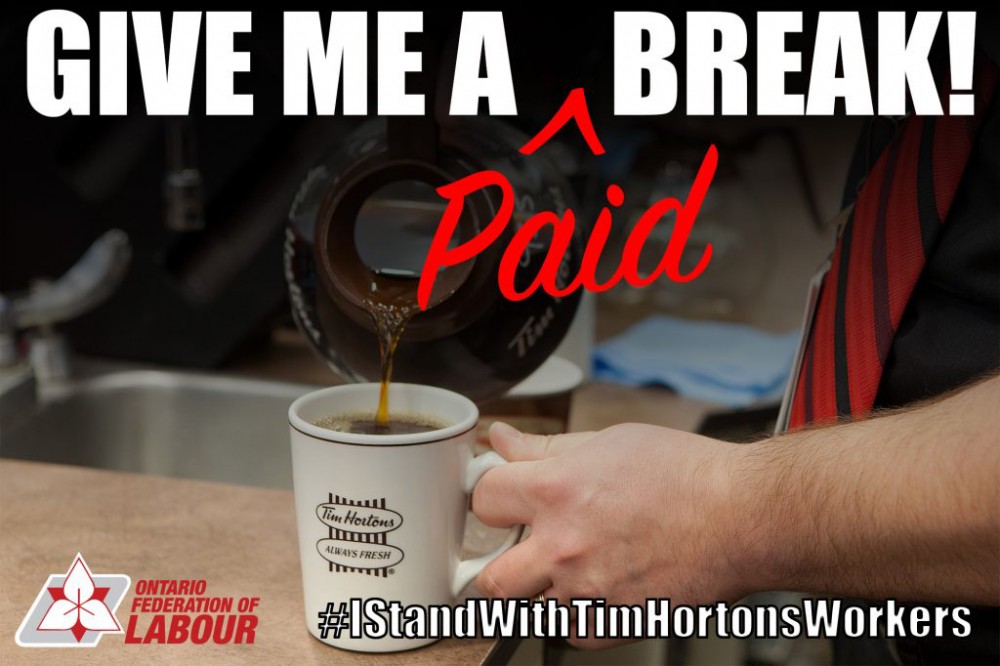

IT BEGAN WITH A PHOTO

For Cobourgers, it began when a local resident with a friend who works at one of the three Tim Hortons locations in town posted a photo of the letter given the workers here. It spelled out the owners’ position and detailed the rollbacks to benefits and paid breaks that would be instituted as the rise in the Ontario minimum wage took effect.

A photo of the letter appeared almost immediately on a Facebook group for area residents. It was shared around and garnered a ton of comments in the NCAP group as well as in groups focusing on local politics.

Initially a boycott was discussed. Friends of the affected workers and some union folks argued against it and the idea had faded by the time the Durham labour council came to everyone’s rescue with a call for solidarity rallies on January 10. When it became known that the franchise owners of two Cobourg locations were actually the offspring of the company’s billionaire founders, the Northumberland and Durham labour councils called for a rally on their (business) doorstep.

Just a reminder: outside of leadership discussions at the labour councils, this was all happening on Facebook — a platform that gets unpleasant with us now and then (always at the worst possible moment) but which is starting to slide in popularity, especially with the 25-and-under set. I’m talking about an organic slide entirely to do with a generational refusal to embrace the social-media habits of old folks. Notice that I’m not referring to the #deletefacebook movement that has sprung up in the wake of the latest FB scandal. Notice that I haven’t even mentioned Cambridge Analytica, data harvesting, tilted U.S. (and other) elections or a certain Brexit referendum in this column. Notice that I’m also not saying “I told you so.”

WHY NOT EMAIL

Why weren’t labour councils and unions getting the word out using email? Why was it only when Leadnow joined the fray and after the petition hosted on the $15 and Fairness website got going that we started to see emails?

Just as tellingly, why did so many, including two national unions and at least a half-dozen large union locals as well as three national media outlets assume that LabourStart was in charge of organizing all those events? Because we sent out emails about them. Emails.

The literature, survey results, studies, personal impressions and Ouija board messaging out there all agree that email is the way to go. So why is there no encouraging uptick in the use of email, and why do I need to keep talking about it? Because there are. . . problems with email. The lists of addresses that should make email work as an organizing tool for unions are small and fragmented. Access is restricted, and use is subject to layers of cautious decision-making, among other things.

Put another way: the tools are there that could enable us to do a much better job. The politics are not.

Blackadder’s Law of Mailing Lists Part One says that if your union has a big list it has so much murky policy on its use or so many layers of decision-making required for authorization that it is all but unusable in an urgent situation like this one. Part Two says that if your union is nimble in this circumstance, then its list is too small to have a real impact.

To put it bluntly: our organizational politics got in the way of our important politics. Generalizing just a bit, the reluctance of local unions to provide their email lists to their parent unions, to labour councils or to provincial labour federations hampered our organizing efforts. Is hampering. Will hamper.

How about tweets? Twitter has become something of an anti-social social network: a one-way street, an online monologue. That trend continues to grow with the increasing popularity of social-media management tools like Hootsuite and TweetDeck, which discourage interaction by placing an extra layer between tweeter and tweetee and by being designed to make it easy to tweet as much as possible. The reading of others’ tweets becomes collateral damage. The new (at the time of writing) and evolving limits on the ability of third-party apps and web services to manage your social-media accounts won’t save the U.S. electoral system from itself, but they will make it harder to use those accounts for more mundane organizing purposes. More on those next time.

So, creating an event for one of the Tim Hortons rallies for a union Facebook page and getting 100 “likes” may generate active notifications to only 10 members. Or fewer. But because Facebook is easy . . . well you get the idea. Easy ain’t best. Or effective.

Members could be expected to hear something in the ether about the Tim Hortons fuss and the calls for solidarity actions and then go looking for information about how to attend them, like LabourStart did when we tried to pull together a detailed list of the January 10th events for a mailing. What we did was search the websites of labour councils and large union locals for announcements of rallies across Ontario. Using Google, the way one might expect your average member to do.

Searching on “Tim Hortons protest” and similar bits of text at that time generated nothing outside of media coverage that didn’t provide timing and location details. NOTHING. With everything buried deep inside Facebook, Google wasn’t going to spit out useful results until the rallies were upon us. Or maybe never.

WHAT ABOUT WEBSITES

What about the websites that we knew were there and went to, whether Google said they had anything Tim Hortons-related on them or not?

That’s when it got depressing. And dangerous.

The depressing bits: While some unions, and the Ontario Federation of Labour (OFL), got it together to announce the January 19 Day of Action on their websites, with all their effort going into Facebook most labour councils had nothing on their sites about either date. Worse still, many, many labour council websites are months, even years, out of date. Years. No exaggeration. Most likely because the effort needed to maintain a website is a lot for a volunteer. Facebook, by providing a standardized, fast and fairly easy-to-use interface is, I suspect, simply seen as a better place to focus any volunteer’s time and energy. Who doesn’t know how to use it, and who wouldn’t find it the easiest way to update information while on the go, as labour folks often are?

ILLUSTRATION: ISTOCK.COM/DRANTE AND BARBARA BAILEY

The dangerous: we don’t own Facebook. I know everyone thinks of it as a public utility. Something that just is, that we can all use for whatever we want, whenever we want. It is not. Remember the SEIU organizing drive at Casino Nova Scotia? One lawyerly letter and your group, your page and possibly even your account are gone — which won’t be noticed by anyone under 25 in just a few years anyway, if the current generational migration away from the Bad Book continues.

All the Timmy’s Day of Action needed was for one or two event listings on Facebook to go Black Bloc on us and jeopardize the whole series of rallies. One lawyerly letter complaining about one Facebook-based call for broken windows could have brought the whole effort down.

THE IMPORTANCE OF ARCHIVING

It gets worse, if a little abstract. Ever tried to go back any length of time and see what was happening then on your Facebook feed? Not fun. But that’s where you may find the near-to-only historical record of the organizing efforts around the Day of Action.

It’s important to know who moved what motion about donating to a worthy cause (like LabourStart) at last April’s local union meeting (contact me for help with wording), so it’s a good thing that we record those kinds of things. But the other history, the “what we tried,” “what worked” and “what didn’t” stuff is hardly ever deliberately recorded.

ILLUSTRATION: ISTOCK.COM/DRANTE AND BARBARA BAILEY

How many of us have looked through a local’s strike archives and found mostly financial records, and almost nothing about the formation of and decision-making by the informal flying picket that ambushed the bread-delivery van at 0400 hours every morning before heading over to the university president’s house to give her a morning wake-up call?

That history isn’t deliberately recorded. No one has the time to make sense of it all, let alone to write it up. It is just there: In a file full of paper leaflets. Or an archive CD. Or a thumbdrive. Or off in a corner of the cloud where we keep the stuff we generate that we don’t want to throw away, recycle or delete. At least it exists and we can learn from it, if need be.

But increasingly it is buried deep in Facebook.

The day Facebook folds or becomes something else or changes its terms of service, much of the history of the National Day of Action in Solidarity with Tim Hortons Workers will disappear. What we did, who did it, how they did it and what the response was, even the photographic records of the signs and the people and the enthusiasm at the rallies will go poof! Organizing is only half about the current struggle. It’s also about building our capacity and improving our chances in the next one. No history, no learning. No learning, no victory.

Yeah, yeah, I know. Facebook is like death and taxes. Let me just respond with: MySpace, Nortel, Eaton’s, BlackBerry, Zellers, Corel, WordPerfect, Sears, bank tellers, home mail delivery and defined-benefit pension plans.

People tell me that generalizing from the personal is a sign of an immature personality. I respond to the people who tell me this as my grandfather Blackadder did: by inviting them to pull my finger. I look at a lot of not just Canadian but also U.S., European, Australian, Indian and Nigerian unions’ websites each week. Allow me to generalize again.

Unions that would never throw away the paper records of their 1927 convention are consigning the records of their political action and organizing and solidarity work to the dustbin of Facebook. How many national union websites are there with nothing new on them? By new I mean less than a month old. Last I looked, one Washington-based international union’s site’s most recent news item was from the spring of 2017. What’s on that site, if not documents and photos? Links to Facebook posts and a rolling Twitter feed box.

Facebook is anchoring the websites. The tail is wagging the dog.

One shrug by the online organizing monopoly that is Facebook and it all evaporates.

So start collecting addresses. And start sharing those lists. And start recording the history of actions on something other than Facebook, kind of like I’ve done here.

And don’t forget to pull my finger.

Derek Blackadder is the co-ordinator for LabourStart in Canada and an honourary member of the Toronto Workers' History Project’s Archive Committee. Feedback and ideas for future WebWork topics welcome.

If you like what you're reading and want to subscribe to Our Times, please go here. Thank you!