Indigenous and Black women have been targeted by violence, because they weave relationships, emotional bonds and always are working to keep families and communities together in the middle of the war . . . They are targeted as economic projects arrive and economic interests try to displace communities. Why? Because women dare to continue building a dignified future for their community, trying as hard as they can not to let their territories be emptied of their people and resources . . . trying not to be forcibly displaced, trying to be able to stay.

— Amelia, Colombian social leader/activist

On International Women’s Day in 2016, Indigenous and Black national and regional organizations, grassroots activists, and social leaders in Colombia launched the Ethnic Commission for Peace and the Defense of Territorial Rights. The Commission was launched specifically to secure a decisive voice for Indigenous and Black communities in the Colombian peace agreements and, from the beginning, dedicated women have been pivotal in steering the Commission’s course and ensuring that its work focuses on gender, families and generations.

These communities have constitutionally recognized political and territorial rights governing over 35 million hectares of collectively titled land. That land is where much of the country’s internal armed conflict has played out and where areas have been prioritized for the implementation of the peace accord signed in 2016. Indigenous and Black communities have been disproportionately affected by a war not of their making. They have been robbed of the right to live in peace and many have been violently displaced from their ancestral territories or forced to flee the country.

"We were involved in social and educational work that was really important to us, related to the empowerment of youth and Afro-Colombian women. Being forced to leave and to come to Canada meant we had to leave that work behind, and it’s been practically dismantled. They took the possibility of our life’s work from us," says Marla, an Afro-Colombian victim of the armed conflict.

After more than 50 years of that devastating conflict, and after four years of intense negotiations between 2012 and 2016, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC–EP), the largest guerrilla organization in Colombia (and in all of Latin America), signed a peace accord with the Colombian government. But Indigenous and Black communities were effectively left out of the peace dialogues until the 11th hour in 2016. It took intense mobilizing in the street, international organizing and the work of the Ethnic Commission, among many other coordinated efforts by Indigenous and Black communities and their allies, to ensure that an “Ethnic Chapter” was formally included in the accord.

Post-Accord Violence Plays Out in Dramatic Ways

In November 2016, the Colombia Peace Accord was approved by Congress and celebrated around the world, touted as finally ending a long and violent chapter in Colombia’s history. It was seen as globally significant for its progressive content, which included, for example, commitments to address the differential effects the violence had on women and LGBTQ+ citizens. The peace accord took hold in 2017, and within it, the political framework for Colombian national development policy was laid out for the following 20 years.

But much of the work, such as reaching a peace agreement with the main remaining guerrilla organization, the National Liberation Army (ELN), has been left undone. Colombia, while having made important advances in the area of truth and justice, remains an intensely divided country with many unresolved structural problems, social and economic disparities, high levels of impunity, discrimination and exclusion, illegal drug and mining economies and overriding agrarian issues — some of the very same issues that so long ago triggered the conflict. Violence is still endemic, and the violence targeting ethnic territories in many regions of “post-accord” Colombia continues to play out in dramatic ways.

Mobilization for peace and Black and Indigenous rights in Northern Cauca, Colombia. PHOTOGRAPH: SHEILA GRUNER

The Colombian Institute for Studies of Development and Peace (Indepaz) registered a shocking 1,000 targeted assassinations of social leaders between the signing of the peace accord and August of 2020. It also recorded a staggering 21 massacres between January 1 and February 25, 2021 alone, involving 59 deaths in just under two months. Black youth, women and girls, social leaders, human rights defenders and the civilian population broadly are being victimized, instilling fear and despair.

Much of the violence waged today in Indigenous and Black territories and against civilian populations is rooted in armed conflict between groups vying for control over what have become economically and geopolitically strategic areas. These groups are engaged in both illegal and legalized economies that include the drug trade, the movement of drugs as well as other goods, infrastructure projects, and extractive industries — especially illegal and unconstitutional mining carried out without community consultations. Profits from illegal mining interests appear to be surpassing those generated by cocaine and other illicit drugs, and mining is becoming just as important a driver of armed actions in these territories

Pacific Coast Communities Mobilize for Peace

In 1991, a new Colombian Constitution legally enshrined the political and territorial rights of “ethnic” groups, including Indigenous, Afro-descendant and Roma people. At the same time, neoliberal economic policies were being implemented in the country, opening the economy to global interests. By the mid-1990s, as collective title was being formally recognized in Afro-descendant and Indigenous regions, illegal players as well as large-scale economic interests saw areas like the Pacific Coast as a new frontier for development. By the end of the decade and into the 2000s, immense turmoil, violence and displacement became the reality for Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities there. The region had become economically and militarily important for many of the armed groups in the country, for the Colombian state, for the United States and for countries, like China and Japan, who are involved in the world’s Pacific region.

Violence briefly waned during the peace talks but has again risen to critical levels. For example, programs advocating the strategy of crop-substitution to dismantle illegal drug economies were outlined in the 2016 Peace Agreement, but numerous Indigenous and Black community leaders have since been assassinated for championing those programs. The Colombian state has no effective presence in the territories and has not provided the support to the constitutionally recognized ethnic governance structures and organizations, effectively abandoning the communities there. Assassinations and massacres are carried out with high levels of impunity.

March for Dignity, by the community of AfroRenacer del Micay, which is experiencing mass forced displacement. The banner reads “#they are killing us.” PHOTOGRAPH: DARWIN TORRES

Buenaventura, on Colombia’s Pacific Coast, is the country’s most important “megaport” city. Paramilitary and gang violence, along with historic levels of structural racism, led to a massive civic strike in 2017 in that city, with more grassroots mobilizations following in 2019 and 2021.

The inhabitants of Quibdo and Tumaco, two other important cities on the Pacific Coast, are experiencing similar levels of violence today as well as long-entrenched structural and institutional racism, all of which disproportionately targets the lives and bodies of Black women, playing out as it does in their neighbourhoods, against their families and community organizations.

In the face of it all, racialized and Indigenous community women and their female leaders are struggling to keep families, organizations and communities together.

Hope and the Humanitarian Accord Now! Campaign

The situation is so dire and has been left unaddressed for so long that now Indigenous and Black communities are pushing for humanitarian accords to be signed between the Colombian government and active armed groups such as the National Liberation Army (ELN). Ethnic organizations including women’s groups in the Choco region publicized a proposal last year urging armed groups to respect human rights and international humanitarian law. The Ethnic Commission for Peace and the Defense of Territorial Rights proposed a grassroots campaign called Acuerdo Humanitario Ya! (Humanitarian Accord Now!), which will be formally launched in 2021.

The goal of the campaign is to have the Colombian government agree to the implementation of humanitarian accords in ethnic territories, such as those on the Pacific Coast, prioritized due to ongoing violence, and to guarantee the implementation of the peace accord, paying particular attention to the Ethnic Chapter. Indigenous and Black communities themselves have developed the content of accords and would seek commitment from armed groups to adhere to them. A number of communities are already engaged in crafting these.

Drawing on protocols embedded in international humanitarian law, these accords would be specific to the needs and framings of the particular community and ethnic group articulating them, and they would be designed to ensure that civilians are no longer targeted by violence and their territories protected from, and left out of, these groups’ military actions.

Building on a long line of policy, activist, advocacy and legislative efforts, the Humanitarian Accord Now! campaign could usher in decisive change and protection for communities.

Roadmap to Peace: the Ethnic Chapter

The current campaign and the promise of the humanitarian accords build especially on the contents of the 2016 Colombia Peace Agreement’s Ethnic Chapter. If taken up in a more integral way, the Ethnic Chapter can provide the pathway to recognizing and ensuring leadership by Indigenous and Black communities — for gendered others, for their families, across generations, territories and communities; as well as for worldwide Black and Indigenous movements and peace processes.

Political will and financing, though, have been inadequate from the start. After its inception, few concrete measures were taken to implement the Ethnic Chapter. The culturally relevant indicators carefully crafted by Black and Indigenous women to take into account broader gender, family and generational relationships as well as realities specific to the territories were neither fully understood nor taken into account. Media attention was scant. Nationally and globally, eyes were averted.

The Colombian Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Co-Existence and Non-Repetition, known as the Colombian Truth Commission, is one tool being used to attempt to heighten awareness. The work of the Commission, carried out in 24 countries, often in those countries, like Canada, where people victimized by violence have been forced to flee over the last 60 years, is to collect testimonies from those affected by or involved in the armed conflict. It is the first Truth Commission that has taken into account the experience of exile as a result of conflict.

Workshop to develop a plan for the women of Yurumangui, middle region of San Antonio. “What characterizes the Black Women of Yurumangui: their resistance” (Dalia Mina) PHOTOGRAPH: DARWIN TORRES

It is voices like Marla’s that are being recorded. She says, "It has felt so contradictory arriving here in Canada. I miss the territory terribly. I miss my family and friends, all the familiar things. On the other hand, I felt so badly treated in Colombia. There is so much racism that I often can’t imagine going back, where they don’t treat you like a human being. There’s racism everywhere I know, here in Canada too, but here I know that I have rights that are taken into account.”

In Canada, the Commission has also documented the role played by labour, human rights, refugee centres and other civil society organizations in supporting Colombian refugees attempting to come here. The work of the Truth Commission in Canada has been supported by labour unions, including the Public Service Alliance of Canada Social Justice Fund, the Steelworkers Humanity Fund, the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), the BC Government and Service Employees’ Union (BCGEU) and the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation (OSSTF).

Canada and the Peace Process

Our country has an important stake in peace in Colombia: Canada committed over $78.4 million in 2016 to the peace process, including what was the largest contribution ($20 million) to the United Nations multi-lateral post-conflict fund. Millions more were allocated to support the implementation of the peace agreement.

Between 2011 and 2017, a reported $240 million in aid flowed from Canada to Colombia. In 2011, Canada and Colombia entered into a free trade agreement, one which contained an important dimension related to monitoring human rights.

Yet over the past two decades, including the last five years following the signing of the peace agreement, human rights and labour organizations have consistently raised red flags about the contradictory role that Canada plays by investing in the country, in the context of brutal human rights abuses.

Human rights organizations and Canadian labour groups have stressed that Colombia has not abided by free trade agreement rules ensuring freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining. These groups note that Colombia has done little to prevent anti-labour violence and has, in fact, often targeted those fighting for labour and human rights. They also point out that the Colombian government has done little to protect against human rights violations, particularly in the resource sector, or to ensure legally mandated free, prior and informed consent is given by Indigenous and Black communities for development projects. This is an especially crucial point, given the ongoing presence of Canadian mining and oil companies, and other economic interests, in the country.

In the past 10 years, Indigenous and Black leaders have formally appeared before the Canadian government, providing firsthand testimony, for example, before the human rights committee and to Global Affairs Canada. The dire situation is on Canada’s radar, but it’s not clear what the Canadian government is doing about it.

An important step the government could take is to ensure effective implementation of the Ethnic Chapter of the peace agreement.

Black and Indigenous movements have developed a powerful, unique and comprehensive roadmap. But the singular opportunity Colombia, Canada and the international community have been given through the Ethnic Chapter to effectively ensure peace will be lost unless a massive and decisive commitment is made: Indigenous and Black governance in Colombia must be supported, and the persistent underlying determinants of violence must be addressed.

Marla speaks a stark truth: “The dehumanization that I have known in Colombia kills.”

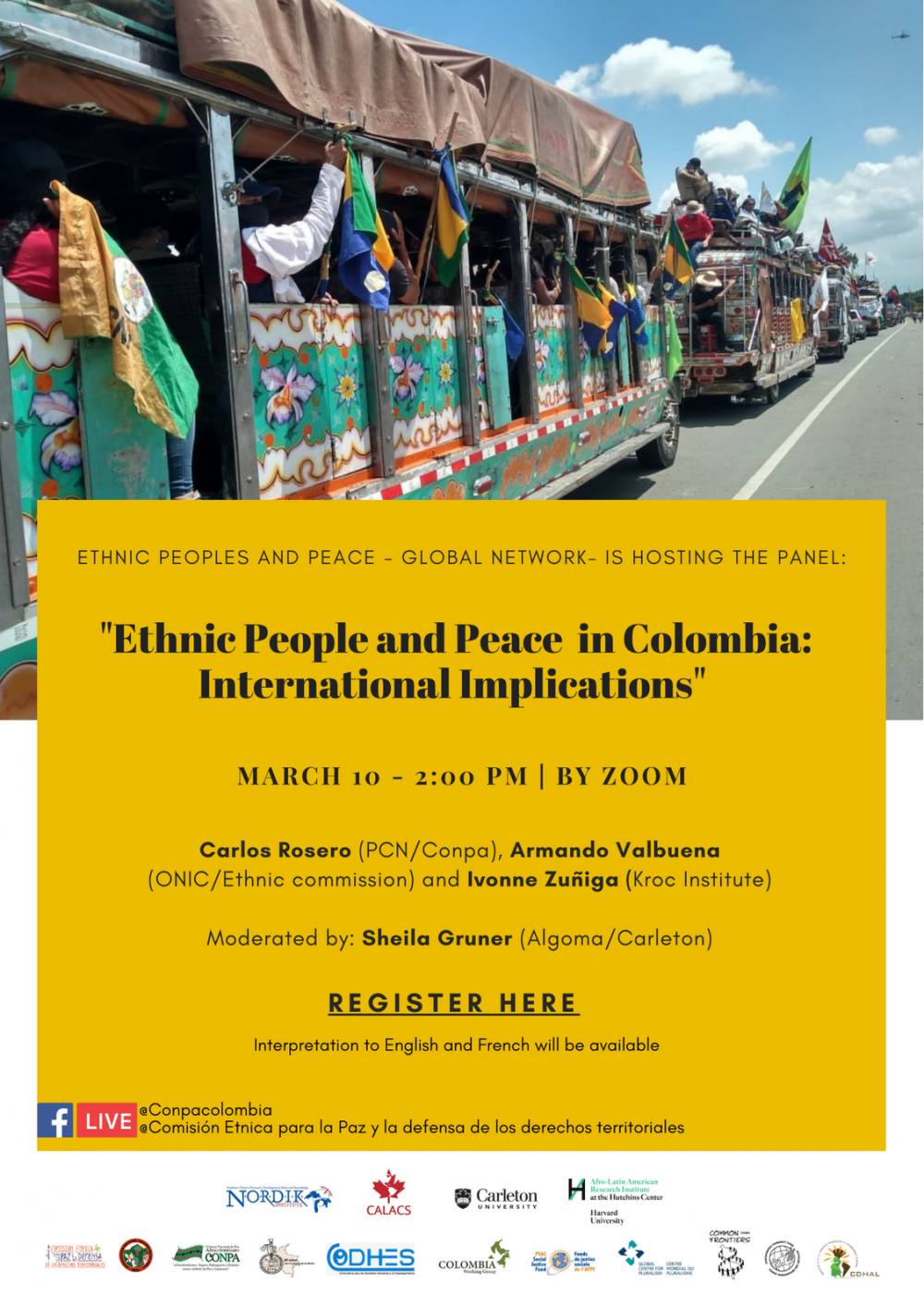

On March 10, 2021 at 2:00 p.m., the Global Network — Ethnic Peoples and Peace initiative will be hosting an online panel “Ethnic People and Peace in Colombia: International Implications.” The panel will discuss the global implications of the Ethnic Chapter of the Colombian Peace Accord. Visit here for more information and to register.

Sheila Gruner is an Associate Professor in Community Economic and Social Development at Algoma University and Adjunct Research Professor at Carleton University affiliated with the Institute for Cultural Mediations. The names Marla and Amelia have been used to protect the identities of the two women quoted in this article.