I call it the "C-word." Capitalism. Even though the system now dominates more of this sorry globe than at any time in history, it's strange that you almost never hear its name. Leaf through an intro economics textbook at any Canadian university and, almost certainly, you'll find that the C-word is not even mentioned. It's as if they're pretending that capitalism is a natural state of affairs and, hence, there's no need to name or define it. (Perhaps more perilous for the status quo: if you were to give the system a name, then you would be implying that there might be other ways to organize economic life.)

In short, just saying "capitalism" out loud makes one sound like a Bolshevik or some other kind of dangerous radical, ready to throw a bomb or otherwise sabotage the smooth functioning of free enterprise.

Photograph By Joshua Berson

EXTRAORDINARY TALENT

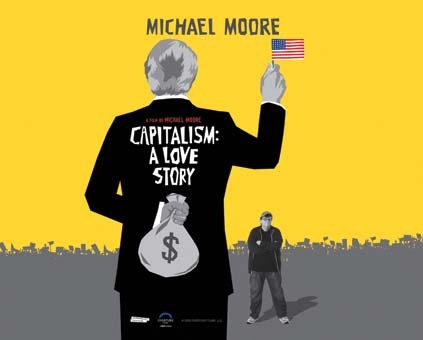

Along comes Michael Moore, very much a dangerous radical. He's dangerous not so much because of his prescriptions for social change, which are muddled and vague (although no more so than the rest of us on the left these days). Rather, what's most dangerous (for capitalism) is his extraordinary talent for communicating, inspiring and entertaining, all in one fell swoop.

Moore's latest feature-length documentary, Capitalism: A Love Story, does all this and more, taking him into the heady terrain of serious political-economy. Now, on top of his famous "ambush" interviews and spoofy humour, he launches into full-fledged structural and historical analysis of the ongoing evolution of modern capitalism. It's the stuff that Ph.D dissertations are made of, yet Moore makes it accessible and entertaining. Above all, he leaves his audience both infuriated and motivated (we can hope) to challenge the irrationalities and hypocrisies that constitute the reality of modern capitalism.

Moore's curious sub-title for his film ("A Love Story") provides the segue into what constitutes perhaps his most personal celluloid journey to date: a glimpse into his own family's past life during the heyday of "Golden Age" capitalism, and then the cruel fading-to-black of that dream. With old photos, home movies, and rather touching interviews with his retired father (a former auto worker in, where else, Flint Michigan), Moore reconstructs the optimism and mass prosperity of that now-bygone era. His review is matter-of-fact and unblinking, not nostalgic. And he explains the unique factors not least of which was the living example of world communism as a powerful, albeit fatally flawed, alternative to the system that forced capitalism, for the first time in its history, to take seriously the economic and political demands of the workers who produce its wealth.

Then Moore presents a tableau of the eventual demise of that largely happy Golden Age model, and its replacement with what we now know as neoliberalism. This historical overview is punchy and bang-on. It identifies the main events and forces behind the return to a harder-nosed, arrogant variant of capitalism, and the main characteristics of the new regime. He shows how this approach to managing the world was the outcome of a deliberate, powerful strategy by elites, in both the financial and the real sides of the economy, to reassert their leadership and their privilege.

HILARIOUS EFFORTS

Singled out for withering satire is the process of "financialization," whereby the production of real stuff (once performed by people like Moore's father) has been supplanted by infatuation with the hyperactive shuffling of paper assets. Moore describes the economic and political triumph of speculation, culminating, of course, in the great meltdown of 2008. No image better captures the pointlessness of this house of cards than Moore's hilarious efforts to get someone on Wall Street anyone on Wall Street to define a "derivative." No one can, which sure casts some light on why the whole damn system melted down.

Moore's on-camera treatment of the fall of the Golden Age, and the rise of neoliberalism,is as good as any I've seen, ensuring that this film will be an immensely important educational resource in the years to come. Less complete and effective is Moore's fuzzy definition of capitalism in the first place. Accompanied, improbably, by actor Wallace Shawn of Princess Bride fame ("That's inconceivable!"), Moore visits a corner store to inspect the weird stuff that's on sale there. The goal is to cast valid doubt on the claim that capitalism's great strength is its ability to respond to the needs and desires of consumers.

But, libertarian ideology aside, the essence of capitalism is not really the inherent desire of humanity to truck and trade, the ability of unregulated markets to clear (supply equalling demand), the alleged primacy of consumer tastes, blah blah blah. There are deeper structural features that truly define this system, which Moore might have emphasized more. In particular: the fact that most work under capitalism is performed through the wage labour relationship, and most production under capitalism is motivated not by human need or desire but by the quest of private companies to generate a profit. That's what makes up capitalism, not the infinite variety of (often useless) stuff on store shelves.

Nevertheless, Moore goes on to successfully document just a few of the infinite ways in which the hunger for private profit leads to outcomes that aren't remotely

welfare-enhancing to the human race: from paying airline pilots salaries so little that they actually qualify for food stamps; to employers making more profit, through insurance bonds, from the premature death of their employees than through their work; to providing private prisons with an economic incentive to lock up as many teenagers as possible, whether they did anything or not.

The film contains numerous memorable moments, shocking and hilarious. One of the most poignant is a man about to lose his job in an Illinois factory. He speaks with brutal, simple passion about what this will mean to him. It's rare that what usually constitutes a mere statistic (just one person among the millions of today's unemployed) is portrayed with such powerful humanity and emotion right on the big screen.

Love it or hate it, we must name capitalism and understand it in order both to get the most out of this system for workers and communities and to figure out how to change the system, in the long run, for the benefit of us and the planet. Moore's film will be a wonderful, valuable tool for those of us working to enhance economic literacy as a pre-requisite for stronger social change movements.