Ramon Antipan came from Chile to Edmonton as a refugee in the late 1970s. In restaurant kitchens, on construction sites and, ultimately at the Edmonton mail depot for Canada Post, he discovered quickly that racialized im/migrant workers are rarely seen as assets, as leaders who bring with them their own histories of fighting injustice.

When he became a proud member of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW) in the 1980s, Antipan noticed right away that as a racialized union activist and Spanish-speaking Chilean of Indigenous decent he was treated differently. "You see that particularly with the white male workers. They look at you like you don't know anything."

Still today, when the broader labour movement speaks of bringing newcomers to Canada into the union family, it often means this as a benevolent gesture of inclusion.

Workers from the global south are seen as largely blank, apolitical slates in need of a trade union education.

A dangerous saviourism can sometimes take hold. When that's mixed with neoliberal ideas of benign tolerance for "third-world" people, it can blatantly contradict the ideals of equity and global solidarity embodied by the Canadian labour movement.

It's also a terrible practice if unions actually want to engage everyone on the shop floor.

ENGAGING THE UNION

Antipan contrasts those attitudes with the welcome he received from two female co-workers when he started as a mail sorter in 1985. "I encountered two great sisters at the plant," he says.

"Right away they approached me and started talking and asking questions. We were working side by side; they explained the union and I played coy. Then they said, 'Well, you know, once you pass the six-month probation, maybe you can go to union meetings and get active.'"

Antipan did just that. The day after he finished probation at the mail depot he declared his intention of becoming shop steward.

What he eventually became was president of the Edmonton local of CUPW.

"'I don't like those Orientals. They speak their language and they are noisy.' I used to hear this a lot during lunch hours at the mail depot," he says.

"There are so many ways that racism hides itself — under attitudes, body language, jokes. I once heard a union shop steward say to his supervisor, 'I don't want to do that work, that's a Negro's work.'

WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT IT

"Despite being in a great union, I discovered that racism was well and alive. When they see me representing our union, some people will look at you like 'why you?' or 'who do you think you are?'"

Antipan remembers the first time he distributed union bulletins. "Some people will look at you and don't want to take it. If it was a white union sister or brother they would take the bulletins. They never said anything to me, because they learned I wouldn't take that shit. But you observe these things, of course. We're not stupid.

"Unions in general, even today, are still very much white-male dominated." Antipan feels that labour activists need to talk about this, openly.

"When I was a local president I was the only non-white person in the office. And, believe me, what I also noticed is there is still a lot of education to be done.

"Being union activists, people are very careful about racism. But sometimes they, consciously or unconsciously, carry it with them."

Antipan recalls working with one union activist whose office walls were covered in beautiful posters advocating an end to racism — an activist who treated Antipan particularly unjustly.

KNOCKING DOWN PERSISTENT BARRIERS

Union communications, he notes, often differ radically from actual union practices: paying eloquent lip service to anti-racism is not the same as actively removing barriers, persistent barriers, to participation and creating processes that will ensure racialized and Indigenous workers are treated fairly.

Antipan believes one of the most powerful routes to change lies in knocking down language barriers.

He decries the wasted potential of some of his fellow union leaders from Chile who were blocked from participating at meaningful levels, and with any kind of real power, in the Canadian labour movement.

"They were tremendous leaders. And I used to tell them, 'why don't you get involved?'"

He makes clear just how much ignoring language barriers can sabotage engagement and sap strength from the labour movement. "I know union leaders from Chile that went to tremendous waste because of language barriers."

Antipan says that differences in union processes and challenges with union communications materials acted as a double barrier. "My fellow Chileans used to tell me union functions are very different here — which is true." For example, "in Chile there was no such thing as your wages being covered when you're doing union work."

A TOOL TO DIVIDE

Antipan contends that unions need to approach racism not as an issue of individual intolerance but as a system embedded in our economic sphere.

"I think racism, or discrimination in general, remains because it is a tool that is used to divide people and keep certain sectors more oppressed than the others. So, therefore, it's actually good for business.

"Let's not forget that racism is an ideology used by the capitalist system to precisely exploit cheap labour. It's there today with the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. Where do they come from? Mostly the third world. How do we pay them? Less than others."

He also points out that racism isn't just an external barrier, but also an internalized one on the part of racialized workers.

"It's not an easy thing because it has more than a century of being established. Even our own people have that sort of mentality and it makes it that much harder. When I got involved in the union I saw how ingrained it is, not only from the majority, it also comes from all of us, as well, in different grades.

"People sometimes say you're inventing things that aren't there," says Antipan.

And that only makes it harder.

THE DYNAMIC DIASPORA

But Antipan is no stranger to difficult circumstances.

When Chilean President Salvador Allende died on September 11, 1973, during a coup orchestrated by Augusto Pinochet and backed by the United States, hundreds of thousands of Chileans fled the country or were exiled.

In addition, at least 2,000 died or were 'disappeared.' Antipan was 25 years old when he, along with his spouse, activist Maria Gloria Antipan, was able to board a flight out of Chile.

They had no say in which Canadian city they would end up in, and like many hopeful Chileans at the time, they saw migration as a temporary measure until the post-coup turmoil was over and they might safely return.

"We spoke figuratively in the Chilean community that we kept a suitcase, ready to go back," he recalls.

The Antipans became part of the dynamic Chilean diaspora community in Edmonton.

Fellow activists and organizers, all of whom are refugees themselves or the children of refugees, include people like Sandra Azocar of Alberta's Friends of Medicare and formerly of the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees; Rod Loyola, current NDP MLA and former president of the University of Alberta Non-Academic Staff Association; and Ricardo Acuña of the Parkland Institute.

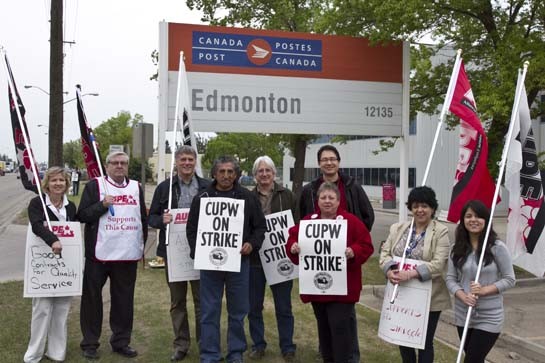

In June 2011, Members Of The Alberta Union Of Public Employees’ (aupe) Executive Joined Postal Workers On Their Picket Line In Edmonton In A Show Of Solidarity. Ramon Antipan Is Pictured In The Centre. Sandra Azocar Of Alberta’s Friends Of Medicare Is On

At the time of his arrest in Temuco, Chile, Antipan was a 24-year-old university student, enrolled in business administration, a fact that deeply amuses him today, given that much of his time since then has been spent sitting on the opposite side of the table, actively taking on employers and businesses.

The Pinochet regime arrested Antipan and charged him with training guerilla fighters and preparing chemical weapons and explosives.

"The reason behind it from my perspective," he says of his arrest and subsequent imprisonment, "was to make an example and instill fear in the population.

"Ultimately, I was arrested for being a supporter of the Allende government."

SPACES OF SOLIDARITY, IF NOT SAFETY

While in jail, Antipan found solidarity and a sense of community among his fellow prisoners.

"There were people of all ages in the prison. The jail ended up being a school for me on how to fight adversity; there was a lot of political discussion.

Every so often we would be stormed by the guards and they would take away stuff, but people in difficult situations become so creative and resourceful. It made me stronger in a lot of ways."

When asked what kinds of things the guards would take away, Antipan responds, "literature — the only 'weapons' we had."

He survived in prison for a year and a half, and was emboldened by the creativity and resourcefulness he encountered.

"We really believed in what we were doing," he says. "It wasn't just a fad — it was about real consciousness."

"Because there were so many of us in the prison who remained enclosed in so big an area, it was easy to engage in conversations. Mind you, at the beginning it was not so easy. We feared infiltrators and informers. But once trust was established, we felt safe to carefully start political conversations and discussions."

The best time to talk, Antipan recalls, was after lock-up. "We could talk more easily from 6 p.m. until midnight, before the jail guards started snooping through the windows in the doors."

ACTIVISM IN ALBERTA

In Alberta, the construction sites Antipan worked on were unionized, but foremen and management were included in the bargaining unit, leaving the union without real teeth.

In 1980, dissatisfied and looking for work, Antipan read about the national president of the postal workers, Jean-Claude Parrot.

"I heard he defied the law and he went to jail, and I said to myself, 'that's the union I want to belong to.'" In 1980, Parrot was jailed for two months for refusing to tell Canadian postal workers to leave their picket lines and return to work.

Antipan set his sights on becoming a postal worker and member of CUPW. But it was no quick transition. The post office, which was federally run at the time, was not hiring landed immigrants.

It was years later in 1985, four years after Canada's federal Post Office Department became a crown corporation and started accepting landed immigrants, that he got a call that his re-application to become a mail sorter had been approved.

DEFYING EXPECTATIONS

"I remember getting a call saying I would have to go downtown to take a small test. It was around lunch time and my daughter was in Grade 1 at that time. I used to go pick her up from school and I remember jumping for joy.

"I embraced her and told her what was going on, that Daddy got a job at the post office, and I was really excited."

Within a decade, Antipan was campaigning to be president of his Edmonton local.

In the lead-up to the union election, a supporter of the other candidate penned a letter to members suggesting that Antipan was ill-suited to represent the 'majority' of workers in the local, and a vote for him would be a vote for a candidate advocating for so-called special interests.

Antipan's campaign manager was outraged and advised that he hit back. But Antipan resisted and ran a positive campaign. It paid off.

There wasn't enough standing room to hold all of the union members who came to vote.

Antipan had been vastly underestimated.

LESSONS FOR LABOUR

He went on to lead the union local from 2003 to 2007, during the years that witnessed increased franchising of the post office: Canada Post began closing official corporate outlets and bringing in franchise counters — like the ones we now see in drugstores — with non-unionized staff who were paid lower wages and given less training.

At the time, Antipan compared the move to the trend he had witnessed in Alberta during the Ralph Klein era, when everything from the province's liquor stores to its vehicle licensing and registration services became privatized.

In his four years as president of the Edmonton Local of CUPW, he and his fellow activists worked tirelessly to make the union more inclusive.

They, for example, pushed to change the dense language of union resolutions to make them more accessible to rank and file workers.

Today, because of the work of Antipan and many others, including CUPW's national women's committee, CUPW resolutions are free of the whereas-laden language that so many union members find intimidating — union members who might otherwise engage far more actively with the movement.

"People don't even understand the word 'whereas.' So we fought that and we changed that, but it took years."

THE POWER OF MULTILINGUALISM

He did so not out of a sense of charity but because too many talented people were being completely overlooked.

"Because of racism a lot of brain power was wasted," he says.

His observations suggest that the labour movement has work to do in seeing multilingualism and the ability to communicate in languages other than English as assets, rather than two-dimensionally perceiving them as shortcomings.

This limiting gaze keeps too many people from accessing meaningful roles as agents of change in their workplaces.

Ultimately, it means that multilingual union activists are blocked in their attempts to connect movements and build meaningful coalitions across a broader spectrum of the workforce.

Ramon Antipan Spoke At The September 11, 2006, Earth Peace Camp, An Edmonton Peace Rally Held On The Common Anniversaries Of The Brutal Chilean Coup Against Democracy, And The Attacks In The U.s. Photograph: Tracy Kolenchuk

When asked about the future of the labour movement, Antipan points to labour laws and the need for activists to focus on them.

"Let's go back 40 years in Chile. The laws were progressive and the rate of unionization was really high. The dictatorship changed everything, starting with the labour laws. Now the rate of unionization in Chile fluctuates between 10 and 20 per cent. So it's about the legislation.

"Alberta, when you read the history, was at one time very progressive. Union members were members of the legislative assembly; then came McCarthyism and the suppression of unions here in Alberta to the point where today we have very low unionization. We have to change the legislation."

Antipan's wealth of experience, ranging from his political imprisonment and student activism in Chile, to his childhood as the son of Indigenous coffee and grain farmers and his life here in Canada, has enriched the labour movement in Alberta.

TRUE SOLIDARITY

In all the work he does, he emphasizes the importance of meaningful solidarity.

"If these systems don't get challenged, they're going to be acceptable. It's an obligation; we can't be sitting idle."

He adds "Charity is easy. You release your guilt over inequality. It has to be based in solidarity. Quite often people are not true to that, even in the labour movement they aren't true to the values of solidarity."

Antipan draws on an example from his days at the Edmonton mail depot to illustrate his point. "One of the things that the union achieved was equal pay for work of equal value. But there was backlash.

"I remember because to a good extent the job is very physical, particularly in the dock area where loading and unloading used to take place. There was a lot of physical work. And I remember that some of the women weren't that big in stature.

"Some of the stuff was heavy for them and I remember some of the men saying 'well she's getting paid the same,' not helping them. People were upset that women were doing this kind of work and didn't want to support them."

NEVER RETIRE FROM BUILDING A BETTER SOCIETY

Antipan is deeply hopeful about the future.

In his 'retirement,' he remains active in the Alberta labour movement and within CUPW.

Last winter, decades after he first applied to be a worksite shop steward, he took part in training new union stewards at the request of the Edmonton and District Labour Council.

He's also hard at work promoting community events, especially social justice initiatives organized by members of Edmonton's Latin American community.

In all he does, he continues to actively combat barriers of racism that keep non-white and Indigenous workers from participating more fully in the labour movement.

MANY HANDS WORKING FOR JUSTICE

In 2007, he took part in a trip organized by the global union federation, UNI-America, to learn from the labour movement in Venezuela how to strengthen a public postal system.

He's also travelled to Cuba, Mexico, Ecuador, Colombia and Chile for union solidarity work.

In 2014, he was honoured with a lifetime CUPW membership.

When asked what keeps him motivated, he goes back to why he got involved in activism in the first place. "There is so much injustice going on. It's hard to stop. You know that you can contribute, even if it's a little, and someone else contributes another piece and the contribution keeps getting bigger. So, hopefully, I'll never say 'enough of this.'

"When you have a dream of a better society, you don't retire from that. The desire to make this world better for everybody is there, no matter how old you are.

"In spite of all the setbacks we have from time to time, we can still see there is a light at the end of this tunnel. I think it is possible, it is possible to make a better world for everybody."

Ishani Weera is a labour activist and social media strategist for unions.